On December 3, 1847, the first issue of the North Star newspaper was published in the city of Rochester. One hundred and seventy one years later, the city again celebrated abolitionist, activist, author, and orator Frederick Douglass in an evening of words and song at Rochester’s Hochstein Hall. The Prophet of Freedom event, co-sponsored by the University of Rochester and Rochester Institute of Technology, featured musical performances, speeches from local leaders and members of Douglass’s family, and a keynote address from noted Douglass biographer David Blight.

Douglass often referenced biblical stories as metaphors in the struggle against slavery. “We cannot understand Douglass without his biblical context, especially the Old Testament, in which he was steeped,” Blight said. A masterful orator—an autodidact who had never enjoyed any sort of formal education—Douglass would artfully weave biblical imagery into his lectures, likening himself at one point to the dove in Noah’s Ark when he returned to visit Baltimore, where he had escaped from slavery in 1838.

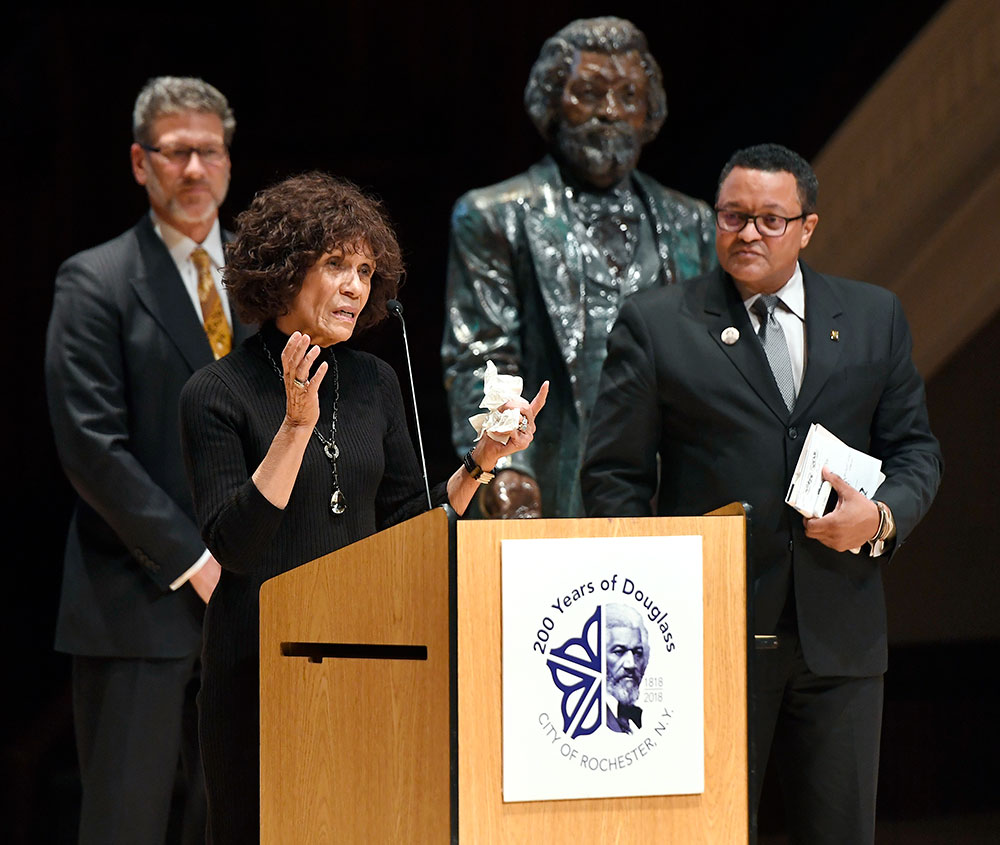

Delivering an impassioned lecture about Douglass’s work in Rochester, the Yale University historian expressed awe at the event’s historic location: 123 years earlier—in 1895—Douglass’s funeral mass had taken place in the very same building, then the Central Presbyterian Church. Now Blight shared the stage with a live-size sculpture of the famed freedom fighter about whom he had written his latest book, a work ten years in the making and listed among the New York Times’ 10 best books of 2018.

The physical proximity of his subject prompted Blight to wonder out loud if Douglass would reach out and grab him by the scruff if he erred on the details. “Speaking here tonight is the most intimidating thing ever—with him looking right over my shoulder,” Blight admitted.

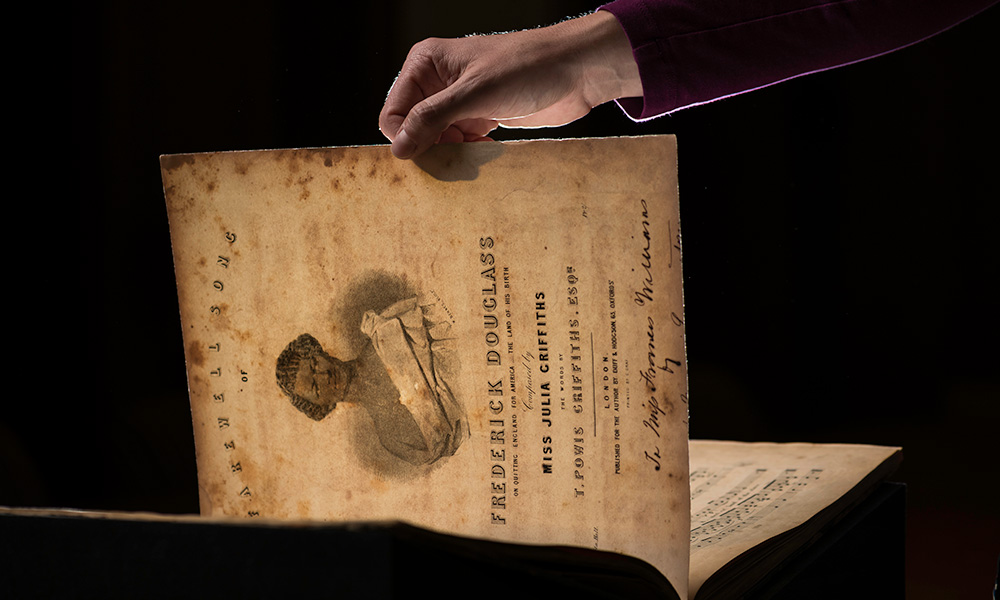

Another highlight took the audience back to Douglass’s angry return to a country still struggling with slavery’s injustice and cruelty with a song not heard in 100 years. Eastman School of Music students Jonathan Rhodes ’20 and doctoral student Lee Wright performed “Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass”—the first performance in a century of the rare, rediscovered piece of music.

Written in the spring of 1847, the song is set against the backdrop of Douglass’s imminent departure from Britain where supporters had raised the necessary funds to buy his legal freedom that allowed the former escaped slave to return to the United States. For 19 months he had traveled across Britain to lecture on the evils of slavery and to avoid being recaptured.

To commemorate his departure, his close companion and fellow abolitionist, the Englishwoman Julia Griffiths, wrote the “Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass.” Only two copies of the sheet music are known to exist—and one of them was acquired earlier this year by the University of Rochester’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation.

“It’s absolutely breathtaking that the actual sheet music has survived,” said Blight, who earlier in the day had seen the original now housed in Rush Rhees Library.

When Douglass first set foot again on American soil he was—quite understandably—full of venom, frequently telling crowds that “I have no country. I have no patriotism.” So strong was his initial antipathy to the United States that fellow abolitionists were asking him to “tone a down a bit,” Blight noted.

Later, as President Lincoln reached out to Douglass, that venom began to metamorphose into a greater feeling of belonging. Ultimately, Blights argued, Douglass found a sense of unity with his fellow Americans, brought together in grief over Lincoln’s assassination in April of 1865. He felt a kinship with his countrymen, a sort of “national redemption through Lincoln’s blood,” Blight said.

But the evening was not just about remembrance and looking back at abolitionist and early civil rights milestones.

“We are the keepers not just of his grave. We are the keepers of his legacy,“ Rochester Mayor Lovely Warren implored the crowd and then quoted Douglass directly: “There is no progress without struggle.”

Douglass’s family was also on hand. Nettie Washington Douglass, who is the great-granddaughter of Booker T. Washington and the great-great granddaughter of Frederick Douglass, told the audience that the new Douglass sculptures by Olivia Kim, marking major Douglass sites in Rochester, had their hands modeled after those of her son—Kenneth Morris, great-great-great grandson to Frederick Douglass.

And the family had a surprise in store: together with co-founder Robert Benz, they announced their desire to relocate their nonprofit Atlanta-based Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives (FDFI) to Rochester “as soon as possible,” adding that they are already looking at suitable brick-and-mortar locations.

The abolitionist organization seeks to continue Douglass’s work by fighting against modern forms of slavery. The FDFI has been educating on human trafficking prevention through national classroom curricula since 2007.

“I realize that all Rochester residents are heirs to his legacy and members of the Douglass family,” said Nettie Washington Douglass. “Rochester is where his legacy will continue to live. I think we can make great things happen here.”

Read more

Rediscovered song honoring Frederick Douglass to be performed for the first time in a century

Read more about the history of this sheet music and how it ended up on this side of the Atlantic, and enjoy a quick video tour of this rare collection.

Waited 100 years for it? Listen here to the rediscovered Frederick Douglass ‘Farewell’ song

The rare song, scored for voice and piano, probably hasn’t been performed in more than a hundred years, with only two known copies of the sheet music in the world. The only known copy in America now resides at the University of Rochester.