The picture most people know of Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the women’s suffrage movement in America is one painted in broad strokes and grand designs. Beyond the vision, grit, and heroism, however, the workaday details of how the movement was actually run—the backroom negotiations, convention planning, grassroots organizing—are largely unknown to history.

Until now.

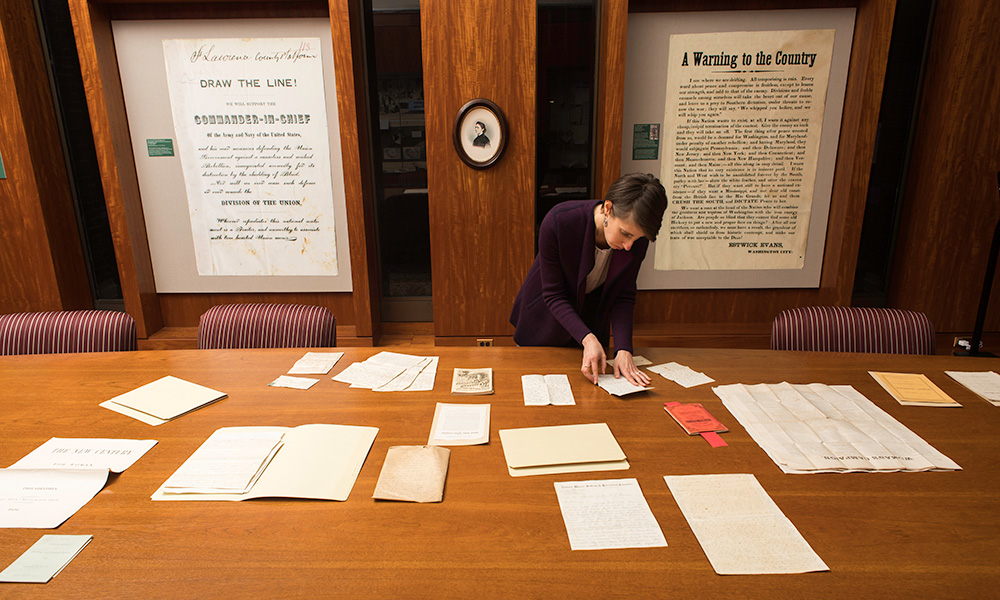

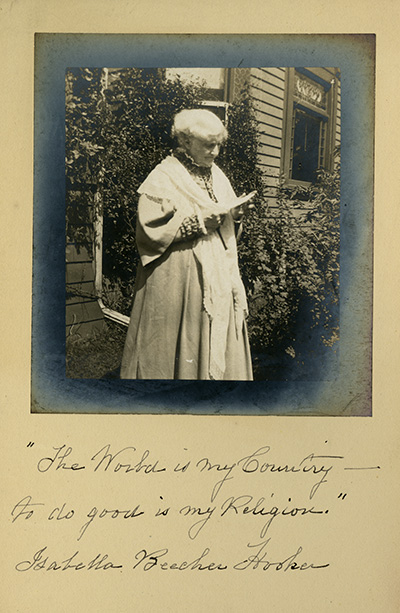

A recently discovered trove of letters, speeches, petitions, photographs, and pamphlets—forgotten for a century in attics, barns, and on porches—now opens a window onto the quotidian details of that historic movement. Originally owned by suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker, the collection includes dozens of letters from fellow movement leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The collection has now found a new home in the University of Rochester’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation (RBSCP).

Part of a notable family of reformers, Hooker was the daughter of the Reverend Lyman Beecher and a half-sister of social reformer and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher, educator Catharine Beecher, and novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Written between 1869 and 1880 by suffragist luminaries to Hooker, the collection is staggering not just for its content but also its size, numbering more than a hundred letters and artifacts.

“It’s an incredibly critical period in this movement,” says Lori Birrell, special collections librarian for historical manuscripts at the RBSCP.

With the 14th Amendment just passed, newly enshrining a host of citizenship rights, and the debate raging over granting black men the right to vote, the time was “very contentious,” adds Birrell, who helped organize the collection’s purchase on behalf of the University. At this juncture, the suffragists saw their chances of being included in the 15th Amendment quickly slipping away, a fear vividly present in their correspondence.

Reading Anthony’s missives makes clear that she considered Hooker her confidante and friend. Hooker had become a central mediator among many strong personalities who, at times, were fiercely at odds with each other over how best to proceed. The letters reveal the lines of engagement and opposition, mapping the nuances of the suffrage movement’s internal politics.

“Something that I’ve been really struck by is just how exhausting it must have been to try to keep going for this long,” says Birrell. “You get to this period in the 1870s and they’ve tried everything—state, national, they tried voting and then got arrested for it in 1872. They’ve tried all of these things and they just kept at it. To read that year after year after year in these letters is simply amazing.”

Adds University’s assistant dean Jessica Lacher-Feldman, who is also the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of RBSCP: “These materials will shed new light on the relationships between important players in the suffrage movement during its most critical period.”

The story of their discovery sounds straight out of PBS’s Antiques Roadshow. George and Libbie Merrow were cleaning out their Bloomfield, Connecticut, home last year when they came across an open wooden crate among family detritus and some antiques.

It sat “just mixed in with old magazines, old funny tools, all sorts of things,” Libbie Merrow recalls.

Inside the roughly two-foot-by-one-and-a-half-foot box, they found stacks of letters, newspaper clippings, and photographs, all sprinkled liberally with mouse droppings. Dusty and probably undisturbed for decades, the small crate had survived two prior moves over the span of about 70 years, having been passed down through the Merrow family twice.

In 1895, George Merrow’s grandfather, also named George, purchased the former Beecher Hooker house at 34 Forest Street in Hartford, Connecticut. Evidently, the Hookers had left their personal papers behind in the attic when the big, elegant home they had built for themselves became too costly, forcing them to sell it. The new owners, just like their famous predecessors, stored their family’s personal and business papers in the attic. After the elder Merrow died in 1943, the papers moved with his son Paul Gurley Merrow to his farm in Mansfield, Connecticut. When Paul died in 1973, his nephew—Libbie’s husband, George—inherited the property.

LISTEN TO THE QUADCAST PODCAST: Ever wonder how leaders of the American women’s suffrage movement drummed up support for their cause? How they sweated the smallest details of their petitions? A recently discovered treasure trove of letters, speeches, photographs, and pamphlets – owned originally by suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker (1822-1907) – and forgotten for a century in attics and barns across Connecticut, now provides a direct window onto the inner mechanics of that historic movement.

In 2010, the couple sold the last of the buildings—the big barn. As part of the deal, the new owner had given the Merrows five years to clean out its contents. Stuffed to the brim with old furniture, tools, two boats, wagons, farm equipment, books and magazines, the barn unwittingly had played a natural hiding spot to the Beecher Hooker papers.

That is until the five-year grace period was up and the family began to clean out in earnest. Having climbed through a broken window into a small side room of the barn in order to open the door that was stuck shut, they discovered a wooden crate with wedding invitations to the marriage of the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. John Hooker. Nothing clicked. Nevertheless, the Merrows decided to keep the box.

“I don’t think that we attached anywhere near the significance to that collection at that time,” says George Merrow, “But we had so many things show up that might be of interest, that we didn’t throw it away at that time.” A family of “pack rats,” is how Libbie Merrow describes the habit of “never throwing away anything that could be kept.”

The Merrows took the musty crate to their home in Bloomfield where they left it for about a year on their porch, only covered by a tarp. When the couple got ready to sell their own home in 2016, they finally brought it into their kitchen for closer inspection. At this point, they had reached out to rare book and manuscript dealers Bob Seymour and Adrienne Horowitz Kitts, with whom they had worked in the past. The dealers painstakingly dusted, researched, and organized the jumbled contents over the span of months.

“I can’t tell you how thrilling it was to hold a letter that she had held more than a hundred years before,” recalls Kitts when she discovered the first letter signed “Susan B. Anthony.”

Libbie Merrow says she was pleased when Kitts told her what she had found. “They called up and said: ‘We have pretty exciting papers here.’ As they went along, they realized it was more and more exciting. It wasn’t just one phone call—it was several phone calls.” Adds George: “We didn’t jump up and down exactly, but it was pretty exciting to hear what they felt the value was.”

Once they finished cataloging, the dealers offered the trove on behalf of their clients to the University of Rochester for purchase. They chose Rochester because of its already existing holdings of John and Isabella Beecher Hooker papers, as well as its Susan B. Anthony collection, one of the largest in the country. The University, geographically located smack-dab in the middle of the 19th-century hotbed of social reform movements, today also boasts papers of what Birrell calls the “supporting cast”—like local activists Isaac and Amy Post, the Porter family, and other Rochesterians who were part of micro-movements with national implications.

“Must not fail to be there…”

The purchase was made with funds from Friends of the University of Rochester Libraries, a gift from retired manuscripts librarian and former assistant director of Rare Books and Special Collections, Mary Huth, and a substantial anonymous gift, augmenting the existing University’s special collections acquisition fund.

“Acquisitions like this are so important,” says Mary Ann Mavrinac, the Andrew H. and Janet Dayton Neilly Dean of Libraries. “They add to our already rich resources, draw researchers, and provide the basis for teaching—which students love as they are working with original manuscripts on topics that speak to them. It’s exciting to hear the voices of these intellectual women come alive.”

However, unlike other Anthony letters already in the University’s holdings, this collection is thoroughly political—rarely personal. The letters show the methods and machinations of (mostly) women bent on changing the status quo that heretofore had relegated them to steerage.

At times, they betray Anthony’s frustration over chronic funding problems, and with women who left the movement for marriage and children. At their rawest, they show her indignation at the general apathy for the cause of equality.

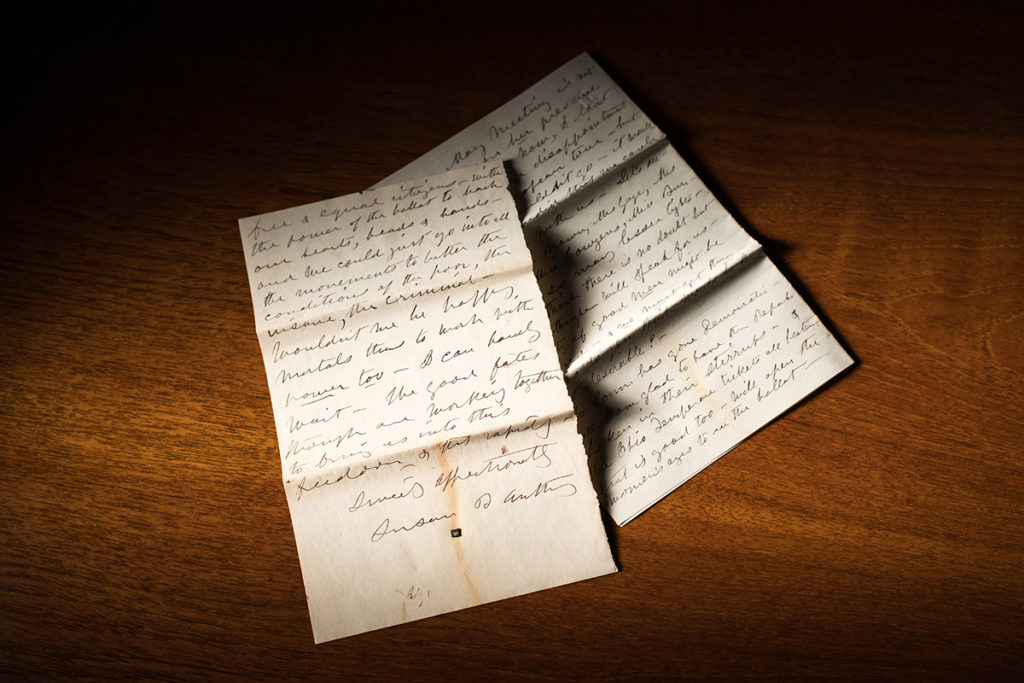

In a letter to Hooker, dated March 19, 1873, Anthony’s impatience is palpable. She tells Hooker of her planning for the suffragists’ regular May meeting in New York City. Writing stream of consciousness to her trusted friend, Anthony admonishes Hooker to show up:

“But you must not fail to be there—for we must make the Welkin ring anew with our War cry for freedom—& our constitutional right to protect it by the ballot—I hear nothing from nobody—All I can do is to run & jump to accomplish the half I see waiting before me—”

Later in the letter, Anthony mentions her impending trial for voting illegally the previous November in Rochester—where she is now speaking to potential jurors.

“I am now fairly into my Monroe County canvass—speaking every night—You [know] a Criminal cannot plead his own case before the Jury—so I am bound to plead it before the whole of Monroe County—from which the twelve must be selected—”

Anthony had been so convincing in her public addresses that the prosecutor eventually decided to move the trial to Canandaigua, in neighboring Ontario County. Without delay, Anthony set out on a lecture tour through this county, too.

Nonetheless, she was found guilty and ordered to pay $100, plus the costs of the prosecution.

While Anthony never paid the fine, the publicity from the trial proved a windfall to the cause. The frequent laments of the suffragists for what was lost by excluding women from public discourse began to sound a newly auspicious note.

“Now wouldn’t it be splendid for us to be free & equal citizens—with the power of the ballot to back our hearts, heads & hands—and we could just go into all the movements to better the conditions of the poor, the insane, the criminal—Wouldn’t we be happy mortals thus to work with power too,” Anthony mused to Hooker in a letter dated April 9, 1874. “I can hardly wait—The good fates though are working together to bring us into this freedom & that rapidly”

Alas, not rapidly enough. Anthony died 14 years before Congress ratified the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting women finally the national right to vote. Anthony’s home state, New York, had done so three years earlier.

To date, only one scholar has seen the newly discovered collection. Ann Gordon, research professor emerita of history at Rutgers University, traveled to Rochester in mid-February.

“Wow,” recalls the noted suffrage movement expert. “It’s quite an amazing collection.”

According to Gordon, the papers will change prevailing scholarship on Beecher Hooker and her brief tenure in leading the suffrage movement, filling in knowledge gaps: “Those few years nobody has paid attention to. We may be able to see what she tried, what techniques she used, what her arguments were, what obstacles she ran into —all those ways that one looks at a political movement and that just aren’t in the story at the moment—and I think we can put them in now,” says the author of the six-volume compilation Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (Rutgers University Press). “Her work is better documented in this collection and it will change how we assess her importance.”

Gordon will not remain for long the only one with access. The collection is now described online and available for research; in the coming months it will be digitized.

“People sometimes think special collections are things hidden away under lock and key. But that’s not what a special collections department in an academic library is like,” says curator Birrell. “These collections are to be used, physically handled, and turned into scholarship. We want scholars to come, and, hopefully be as excited as we are about this stunning discovery.”

Collections on this scale are rare, says Gordon. “An individual letter may surface at auction or at a dealer, but we don’t often find a collection of this size. It’s a real treat.”