Here’s a challenge: How do you convey a 91,000-square-foot castle with more than 160 rooms on the Ghana coast, back to Rochester, so at any time you could take a virtual tour as if you were really there? Or study the castle’s structure in such detail that every brick can be measured within 1-to-2mm accuracy? Or even look at a “Xerox copy” of every layer or two of an archaeological excavation that has since been filled in?

An interdisciplinary team of faculty and students from the University of Rochester and the University of Syracuse, in collaboration with the University of Ghana, is doing all of this at Elmina Castle and nearby Fort Amsterdam. How? With a drone, laser scanning, photogrammetry, digital solid modeling, and traditional field recording techniques.

“We want to create a good (digital) model,” says Chris Muir, professor of mechanical engineering, who has helped conduct the Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School each of the last three summers. “That’s the backbone for this whole project.”

One version, for example, created primarily with photographs, enables you to take a virtual tour of Elmina. “It looks real, so you don’t have to be there to see what one of the vaulted rooms looks like,” Muir says. This is especially useful as a portal to help history students virtually immerse themselves in the historic structures and cultures they study, says Michael Jarvis, an associate professor of history who also helps conduct the field school.

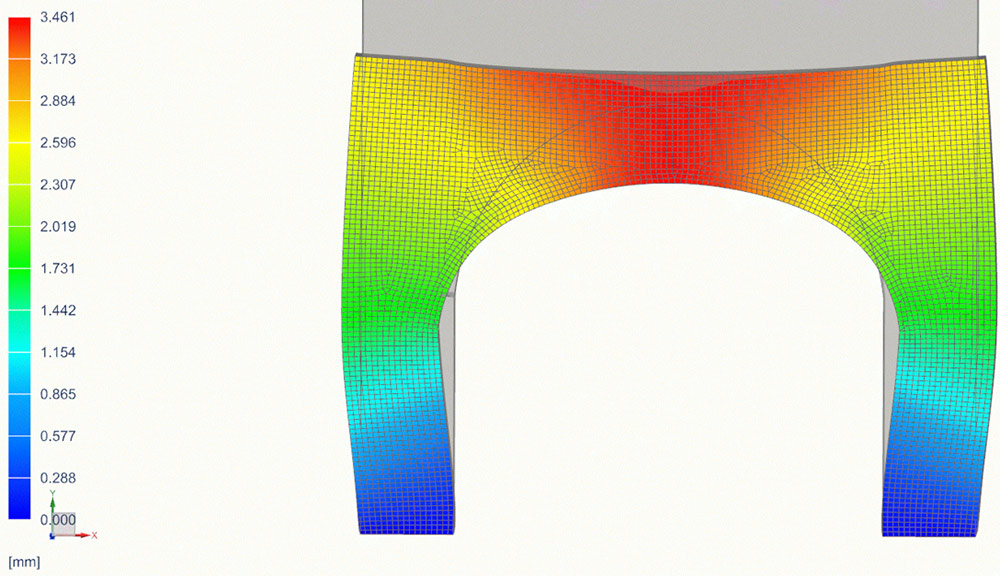

Another model enables detailed analysis of structures and weak points. Based on data-rich laser scans, “you can then use finite element analysis to look at where the stresses are going to occur, and to help guide remediation work or other repairs,” Muir says. That helps ensure the preservation of the Ghana coast structures, which are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The students who participate in the field school—many of whom have no previous experience with surveying and digital modeling—must gather mountains of data to feed into these models. Muir, who guides the students in surveying, computer aided design (CAD) and finite element analysis, and Jarvis, who guides them in laser scanning and photogrammetry, describe the tools that the field school uses.

Creating a shell

To obtain basic dimensions of a room or hallway, “we start the students off with a tape measure and a piece of paper,” Muir says. They also use hand-held laser distance measuring devices (like ones sold at retail stores) to measure high ceilings in vaults.

Dimensions of the overall castle, which is about two football fields long, are taken with a total station transit tool, which was purchased with a Wadsworth C. Sykes Engineering Award. The total station uses a high-power laser to measure points over long distances, Muir explains. Aim through the rangefinder at a desired point. Click a button. The distance is recorded and the transit can then be rotated to the next point. Each measurement is saved and can later be downloaded to CAD.

The dimension data helps create shell-like models of the castle and individual rooms, which can then be “painted” over with information of two kinds.

MAKING A MODEL | Here is a photogrammetry model of a ground floor storage room in Elmina Castle created by Seungju Yeo, ’20 of mechanical engineering in June 2018. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo)

68,000 photos ‘stitched’ together

Photographs provide a realistic, web-accessible 3D view of all these spaces. But this requires taking literally thousands of photographs from multiple angles.

For external views of the castle, Jarvis shows students how to use a DJI Phantom4 drone, purchased through the Archaeology, Technology and Historical Structures Program. The drone takes 16-megapixel, top-down images every second as it zig-zags overhead, gathering a total of 1,000 or so images. Another 2,000 photos, taken from ground level, are then “stitched together” with the aerial images using photogrammetry software. This produces a digital 3D model of the castle’s exterior, accurate to within a few centimeters.

Another 200 to 500 photos must then be taken of each of the individual rooms – another 65,000 or so photos in all.

To process that many photos with photogrammetry software “you need very powerful computers,” Jarvis says. He has assembled his own computer system – basically four computers with graphic cards, all working in tandem – to cut the processing time from 25 to 30 days three years ago, to 3-4 days now.

3D LASER CAPTURE | Digital scanning by professors Michael Jarvis and Chris Muir shows the same room but from the outside, made with the Faro laser scanner. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo)

35 billion points from a laser scanner

For even more data-rich, textured models of the rooms, Jarvis and the students use a Faro laser scanner. Unlike a total station, which gathers a smaller number of discrete measurements, the laser scanner, set on a tripod, rotates continually in all directions, even in total darkness, measuring the distances to literally millions of points of contact.

About 98 percent of the castle’s interior has been scanned, resulting in about 35 billion points.

“With a 3D laser scan capture, you can drop through floors, you could be inside walls, you can study how the castle fits together, which then gives you insights into a building’s sequence,” Jarvis says. “If one room doesn’t line up with the next room, you know they weren’t built at the same time.”

IDENTIFYING POINTS OF WEAKNESS | This finite element analysis model of the same room, created by Katherine Korslund ’20 of mechanical engineering, simulates the displacement of the same room when the column supporting the vault is removed. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo)

These data rich scans help feed the structural models that students create with Siemens NX—a high-end computer aided design, manufacturing, and engineering software program. They can then apply finite element analysis to identify weak points and to simulate how much lateral stress from an earthquake, for example, would cause a vault to collapse.

Muir uses NX in the senior design courses he teaches at the University. The software is also used extensively in industries like aerospace. The application to historic structures is novel, to say the least.

“I have talked to representatives from NX who can’t believe what we’re doing with the tool—in a good way,” Muir says. “I don’t think there are any other schools using this tool in quite the same way.”

For students, the benefits extend beyond the immediate collection and subsequent analysis of data.

“As a result of this data collection, we have started to acquire not only the skillset, but the mindset of a researcher,” said Gilda DeDona ’18 of chemical engineering, who participated in the field school during the summer of 2017. “If I have learned anything from this experience, it’s to never be content to take a structure for what it appears to be, but rather to question, and attempt to explain, what we are seeing and why we see it.”