Democracy is probably not in the cards for Sudan any time soon.

When widespread protests erupted in April in this northeastern African nation, the military seized the opportunity and overthrew the country’s brutal dictator of the past 30 years, President Omar Hassan al-Bashir. But his replacement—no other than his former military enforcer Lt. General Mohamed Hamdan—is unlikely to deliver peace and democracy. Not only is Hamdan accused of genocide in Darfur, he has also now sent troops to assault, rape, and kill Sudan’s pro-democracy protesters.

Sudan is not alone when it comes to bloodshed in postcolonial Africa. Violent political events, rooted in ethnic conflicts, have plagued sub-Saharan Africa since independence, causing millions of deaths and hampering economic development. Yet, nearly 80 percent of the continent’s major ethnic groups have never participated in any civil war.

Of course, Africa exhibits considerable variation. Why, for example, have civil wars and insurgencies occurred in Sudan and Uganda, but not Kenya? Why did Benin experience several coups and coups attempts after independence but not Côte d’Ivoire?

Jack Paine, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Rochester, is studying the factors that underlie ethnic strife. In a recent paper, “Ethnic Violence in Africa: Destructive Legacies of Pre-Colonial States,” published in International Organization, he explores why civil wars and coups d’état occur more frequently in some sub-Saharan African countries than others. What makes violence more likely?

Much previous research has looked to the postcolonial period for answers. Yet, taking a longer term perspective, Paine found the origins in precolonial political organization. In short, African countries that include ethnic groups that were organized as states prior to European colonization are at much higher risk for violence.

“Many African countries have experienced considerable ethnic strife,” says Paine. “These tensions have roots in deeper historical events. Frequently, precolonial political organizations sowed the seeds of later discord.”

The precolonial roots of postcolonial conflict

Essentially, authoritarian rulers face similar tradeoffs: If they try to buy off potential enemies by including them in the ruling coalition, they risk elevating opponents to positions of power where they can overthrow the ruler in a coup. However, if rulers deny rivals important cabinet posts, the excluded groups may launch an outsider rebellion to try to topple the government.

According to Paine, in many African nations, insecure postcolonial leaders decided against inclusive coalitions for fear of an insider putsch. That was especially the case in countries that incorporated an ethnic group with a precolonial state, given the general absence of interethnic political parties and the corresponding inability to commit to bargains.

“Distinct states and identities created privileged subsets of the population that, when independence became imminent in the 1950s and 1960s, were unwilling to forge organizational ties with other ethnic groups,” Paine says.

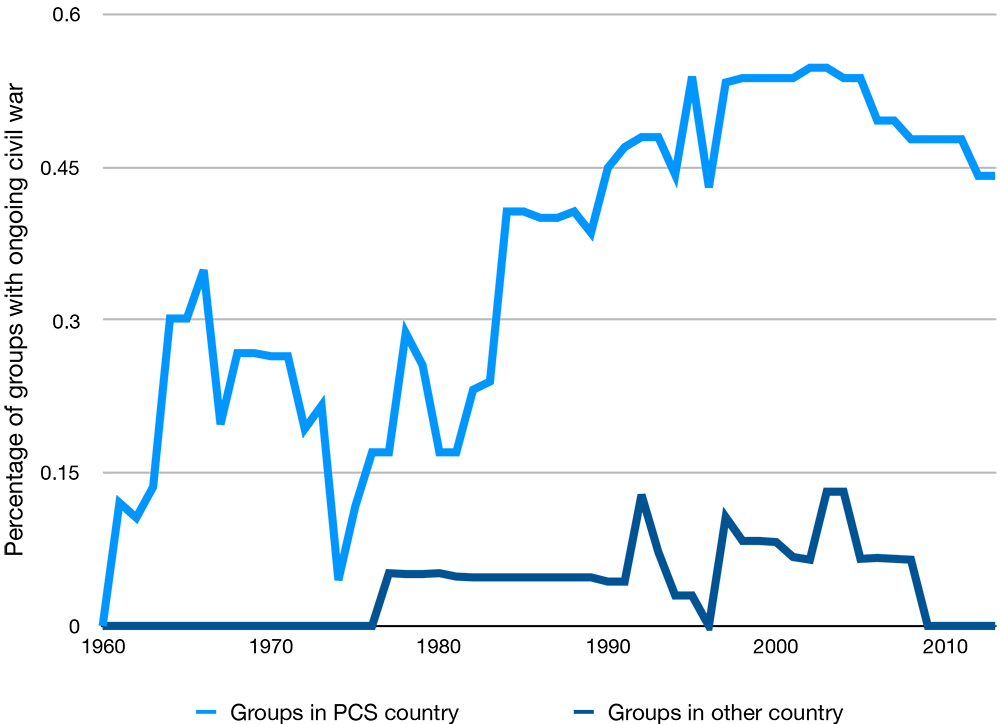

He also discovered a direct spillover effect: ethnic groups organized as a precolonial state—so called PCS groups—within a country increased the likelihood of conflict for all groups in that country.

Compiling a new data set on precolonial African states, Paine analyzed data covering the period from the year in which a country became independent—until 2013. Up to end of the Cold War in 1989 the numbers are especially striking: 30 of the 32 major civil wars in Africa occurred in countries with a precolonial state—despite the fact that countries without PCS groups accounted for only 39 percent of observations in the data set.

In short, almost every major civil war in sub-Saharan Africa during the Cold War era occurred in a country with a PCS, or precolonial state, group.

Explaining the variance within Africa

While plenty of researchers have shown how ethnicity affects violence, Paine argues that most existing theories do not sufficiently explain variations within Africa.

During the precolonial period, roughly before 1884, Africa featured diverse forms of political organization, ranging from stateless societies such as the Maasai in Kenya, to hierarchically organized societies with standing armies such as the Dahomey in Benin. Centralized states often participated in violent activities to promote intergroup inequality, says Paine.

During the subsequent high colonial period, roughly from 1900 to 1945, PCS groups were elevated in the colonial governance hierarchy. According to Paine, they became natural allies because ruling through existing local political hierarchies reduced colonial administrative costs. Examples include the Asante in Ghana, Buganda in Uganda, Hausa and Fulani in Nigeria, and Lozi in Zambia. Paine points out that this kind of governance strategy was most closely associated with British rule, which favored indirect governance.

“The fact that people differ in their language and origins matters less than the fact that people differ in their history of political interactions—before, during, and after the colonial period,” says Paine.

That’s why common policy recommendations for ending civil wars may not work without understanding the long-term effects of factors such as precolonial statehood, warns Paine. For example, promoting inclusive power-sharing agreements will likely not stem violence in PCS countries because the internal security dilemma might destabilize such arrangements.

Deepening democratic institutions in order to increase the credibility of power-sharing agreements—and the hope that over time the legacies of distinct statehood will lessen—provide a possible but uncertain path out of the coup and civil war trap for many PCS countries.

“Even if changes over time can help ease earlier tensions caused by precolonial statehood, the unfortunate consequences of these historical differences continue to linger in many African countries to the present day,” Paine says.