What does it mean, in a secular age, to be driven by belief? How have writers answered the question, what is belief? New books by John Givens, a professor of Russian and chair of the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures, and John Michael, a professor of English and director of the American Studies program, probe the question. Both scholars consider how sweeping cultural and technological changes influenced the works of iconic writers.

The books grew out of their authors’ experiences in the classroom, helping undergraduates to understand literature through close analysis and examination of historical and cultural contexts. In their arguments, Givens and Michael also respond to and amplify philosopher Charles Taylor’s influential work on secularism, a concept that Taylor argues is really a reformulation, not a rejection, of belief.

While Michael and Givens offer nuanced readings of, respectively, 19th-century American and 19th- and 20th-century Russian literature, the issues at stake in their works have a wide resonance.

“Can one believe in a metaphysical other reality in light of science, the social sciences, and progressive thinking?” Givens asks, describing the fundamental concern of his book. “And if you can, how might the ways these authors themselves grappled with this question help you understand what belief might look like in a secular age?”

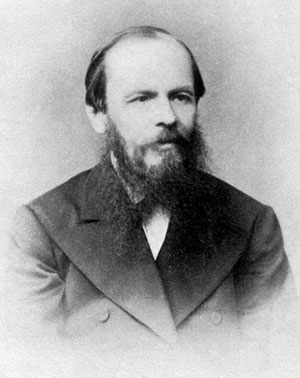

Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky had been jailed for eight months when he was taken to Semyonovsky Square in December 1849 to be executed. His offense was his participation in the Petrashevsky Circle, a utopian socialist discussion group. Dostoevsky watched as three of his arrested companions were tied to posts; the executioners raised their rifles against them. And then, suddenly, a courier on horseback galloped in, carrying news that Tsar Nicholas I had commuted the men’s sentences to hard labor in Siberia. The planned execution had all been a ruse, performed to terrify the men.

“This was a defining moment for Dostoevsky, perhaps even for his faith,” says Givens. On the way to Siberia, Dostoevsky encountered Natal’ia Fonvizina, the wife of an exiled Decembrist revolutionary, and she gave Dostoevsky a copy of the New Testament to read during his imprisonment. After his release in 1854, Dostoevsky wrote to her a now famous letter, in which he called himself a “child of this century, a child of doubt and disbelief”—but also declared that “there is nothing more beautiful, more profound, more sympathetic, more reasonable, more courageous, and more perfect than Christ.” He even went on to announce, “I would sooner remain with Christ than with the truth.”

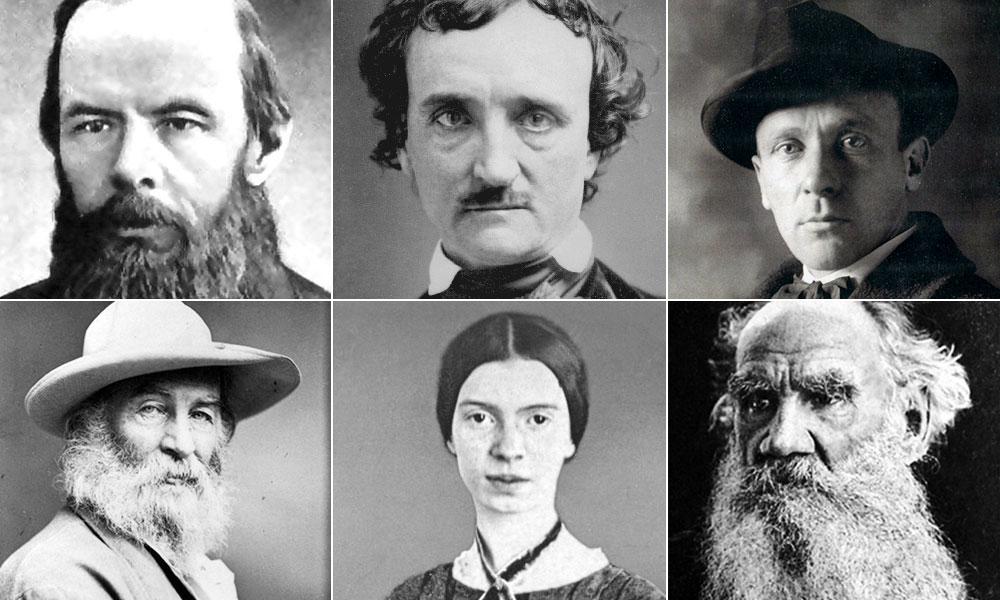

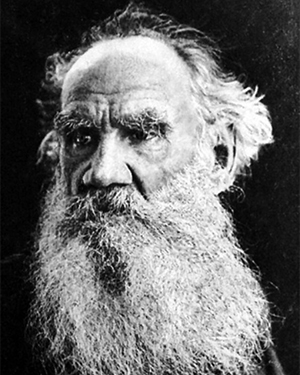

How to understand his seemingly paradoxical thinking? In The Image of Christ in Russian Literature: Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Bulgakov, Pasternak, Givens argues that the letter, like much of Dostoevsky’s work, expresses his complicated relationship to faith and doubt, a complexity born of trying to express belief in a non-believing age. Like his contemporary Leo Tolstoy and their 20th-century novelistic heirs Mikhail Bulgakov and Boris Pasternak, Dostoevsky turned to a rhetorical strategy of assertion through negation. The four writers “occupy a middle theological position somewhere between faith and skepticism,” Givens writes.

The author of Prodigal Son: Vasilii Shukshin in Soviet Russian Culture (Northwestern University Press, 2000), an examination of an influential, Siberian-born actor, writer, and film director, Givens found the idea for his new book in the classroom: “I often had to give my students a primer in basic Christian beliefs and who Jesus was—but I realized that to a certain extent, maybe I didn’t need to do that, because what Dostoevsky was doing with Christ in his works was much more provocative and in its own right providing a definition or an image of Jesus for people who might not have a lot of familiarity with him.”

Givens terms the 1800s a “century of unbelief” and examines how Dostoevsky—whose books include The Brothers Karamazov, Crime and Punishment, and The Idiot— and Tolstoy wrote about Christian teaching and spirituality in an age when secularism was taking hold in Russia. After publishing his masterworks, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Tolstoy experienced a profound crisis in the 1870s, when he confronted his mortality and sought to find meaning in life that transcended his literary fame. Ultimately, he set out to create a “new religion,” one that swept away the “mud and slime” of church mysticism and focused concretely on Jesus’s moral teachings. He saw Jesus from a secular point of view—a mortal man, but also a revolutionary one, with a “blueprint for establishing true justice on earth,” Givens writes.

He argues that Dostoevsky and Tolstoy expressed their own conceptions of faith in what Dostoevsky once called “our negative age” through the literary deployment of a theological approach of the Eastern Orthodox Church called apophatism—the idea that the divine can be known only through that which it is not. As a literary device, apophatism takes shape as indirection and negative assertion. Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, and later Bulgakov and Pasternak, offer the most enduring depictions of Christ in Russian literature of the last two centuries, Givens contends, although their representations are made through allusion and even by “contradiction, refutation, or radical theological reconfiguration.”

Both Christian belief and the act of believing itself was a source of anxiety, not consolation, in 19th-century Russia, Givens argues. The 20th-century Soviet era, however, was a time when “belief was very much in the air, even as religion was suppressed.” And despite its repudiation, Christianity remained a cultural backdrop. Russian radicals pointed to Jesus as a kind of socialist forerunner, he notes, and the revolutionary movement in Russia had a “quasi-religious” character, extending iconographic status to Soviet leaders like Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.

Writing in the Soviet era, Bulgakov completed his novel Master and Margarita in 1940, just before his death. His widow kept the manuscript private; it wasn’t published until the mid-1960s, in a censored form. The novel tells a story of the Devil’s arrival in 1930s Moscow; he seeks Margarita, who loved Master, the author of a novel about Pontius Pilate. Bulgakov makes reference to Stalin without ever drawing him into the story directly. Pasternak, in his 1957 novel Doctor Zhivago—published first in Italy in 1957, a year before Pasternak was compelled to decline the Nobel Prize for Literature, and published in Russia only in 1988—also relies on strategies of obliqueness, but both authors invoke improbable Christ figures in narratives that allude to the death and suffering of Jesus.

Givens sets his task as understanding why these authors turned to apophatism, why they affirmed Jesus “through strategies of negation or through weak or failed Christ figures,” he writes. He draws on Taylor’s conception of cultural “cross pressures” to understand how Russian writers responded to the dilemma of finding faith “made fragile by the claims of science, reason, and progressive social attitudes,” while also finding their faith fortified by a sense that purely rational explanations of life are insufficient.

The Image of Christ in Russian Literature is about “something familiar to all of us—the understanding of what belief might be in a secular age,” Given says. “What does it look like? The quandaries Dostoevsky and Tolstoy faced in the 19th century are the same that any believer would face now. It’s a book that looks at how the secular and the metaphysical might cohabit and how these deep-thinking writers themselves grappled with the limits of belief in a secular age.”

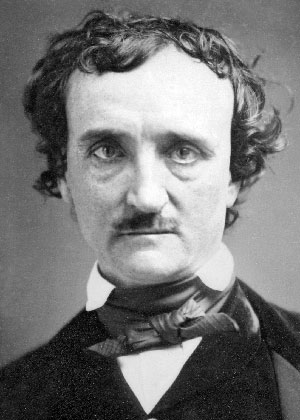

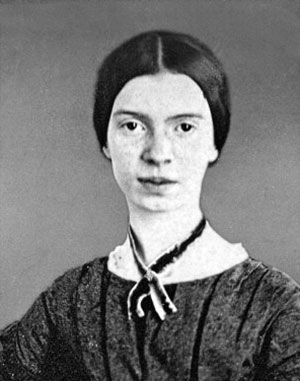

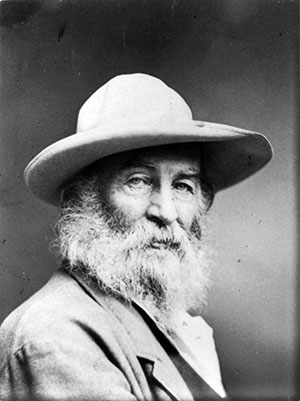

Like Givens, John Michael, a professor of English specializing in 19th-century American literature, found inspiration in teaching for his new book, Secular Lyric: The Modernization of the Poem in Poe, Whitman, and Dickinson (Fordham University Press, 2018). For some years, Michael had offered a course on Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, and Emily Dickinson—the “big three” 19th-century American poets. He was interested in how they stand together as a group, not just as the only American poets from the period who are still commonly read and taught, but also because “they’re remarkably different from the poets among whom they worked,” he says.

Lyric poetry, as its name suggests, is songlike; in ancient Greece, lyric verse was traditionally accompanied by the music of the lyre. A personally expressive form of poetry, lyric gives voice to an individual speaker’s thoughts and feelings. Poe, Whitman, and Dickinson knew well the genre’s history—and bucked its conventions. “They weren’t just peculiar by chance; they were actually peculiar by design,” says Michael. “They worked hard as self-conscious poets not to do what their audiences expected of them.”

Readers in 19th-century America were accustomed to finding accessible meaning and consolation in poetry’s lines. In its first formulation, Michael’s course focused on the three poets’ representations of death. Investigating the history of such representations, he began to reflect on the ways that secularism changed Western responses to mortality in the 19th and 20th centuries.

But viewing death as a context for the poems didn’t explain to Michael why the three poets’ relationship to meaning seemed to change. They weren’t unique in their rejection of consolation, nor in their questioning of meaning—poets throughout history have done that. But Poe, Whitman, and Dickinson moved such ideas to the foreground of their works, and their doubt and skepticism have become touchstones for later generations of poets.

Michael’s latest works grows out of his longstanding interest in skepticism. His previous books include Emerson and Skepticism: The Cipher of the World (Johns Hopkins, 1988), Anxious Intellects: Academic Professionals, Public Intellectuals, and Enlightenment Values (Duke 2000), and Identity and the Failure of America from Thomas Jefferson to the War on Terror (University of Minnesota 2008).

“Any skeptic will tell you that there’s no belief that can ultimately be grounded, and by grounded I mean made secure from a counterargument,” Michael says. He found in Taylor’s work a useful lens for understanding the status and ramifications of belief in the 19th century, when a loss of religious belief was associated with poetic loss, a process of substituting rationality for enchantment. But, like Taylor, Michael contends that secularism isn’t the end of belief; rather, it’s a change in the conditions of believing. Secularization involves the “realization that every understanding of the world, even those based in science, rationality, and the human yearning for progress, rests ultimately on belief,” Michael writes.

For Dickinson, Whitman, and Poe, “secularization becomes the inspiration for—or perhaps the provocation of—lyric. In exploring the potentials and incapacities of lyric in a secular age, each of these poets contributed to the transatlantic phenomenon of the modernization of poetry,” he writes.

Most of their contemporaries—like the wildly successful Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for example, who wrote such rousing poems as “Excelsior” and “Paul Revere’s Ride,” didn’t share their perspective. Their position also ran afoul of that of Transcendentalism’s founder, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who in his essay “The Poet” insists that poetry should convey truth. In contrast, Whitman, Dickinson, and Poe “are poets who seem mostly interested in confusing and frustrating the reader’s desire for meaning,” says Michael.

But while they were writing against the grain of some popular cultural traditions, they were also registering changes emblematic of their time. Nineteenth-century technological advances made possible a true literary mass market, and writers became conscious of their readers in a new way—even the legendarily reclusive Dickinson. “A lot of her poetry ponders the issue of who will read it and what the world will say about it,” he says.

To be a writer, Michael notes, is to “confront the crowd.” And in the 1800s, composing a lyric poem became a complicated proposition as poets confronted a mass audience of increasingly diverse readers. “The foregrounded ‘I’ of the lyric always suggests the presence of a ‘you,’ an other who hears or overhears the poem, the audience who reads it, Michael writes.

The pressure of anonymous, heterogeneous readers—“the materialization of the secular crowd as a provocation of and a challenge to lyric”—and how Poe, Whitman, and Dickinson shaped their work in response is the focus of Michael’s book.

He devotes two chapters to each of the three poets, concluding with a chapter on Dickinson and fragmentation. Her poems are famously fragmented, and Michael sees in her distinctive style a marker of her age: “In Dickinson, the fact of existence orients itself toward the questions of meaning that remain questions and a hoped-for wholeness that death frames and fragments. Death and fragmentation suggest the irony and greatness, the terror and abjection of life. For Dickinson, this is the texture of life in a secular age.”

Writers and readers are molded by their times; their own sensibilities, in turn, help to fashion their eras. In his close readings of Russian novels, Givens investigates how Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Bulgakov, and Pasternak wrote against the grain of their society, using intricate literary strategies to express beliefs not widely shared by their readers or encouraged by authorities. The poets in Michael’s book presage modern literary concerns, registering changes that were beginning to be felt in the popular culture, even as more conventional writers of the period resisted them.