Rochester scientists discover that strong immune systems and protection from genes are at play—and the findings could apply to human longevity.

A new study that looks at why long-lived bats do not get cancer has broken new ground about the biological defenses that resist the disease.

Reported in the journal Nature Communications, a University of Rochester research team found that four common species of bats have superpowers allowing them to live up to 35 years, which is equal to about 180 human years, without cancer.

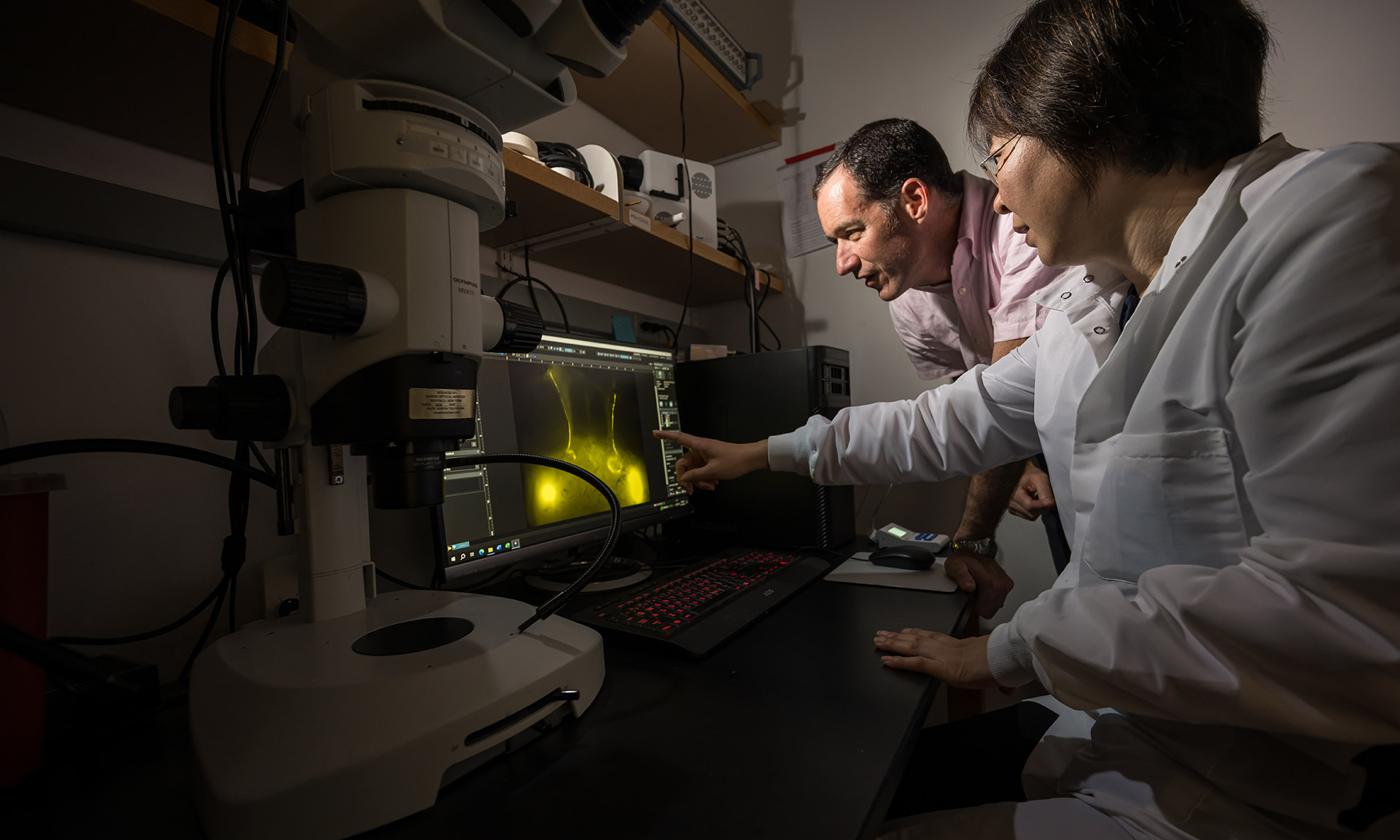

The work was led by Vera Gorbunova, the Doris Johns Cherry Professor in the departments of biology and of medicine, and Andrei Seluanov, a Dean’s Professor of Biology, who are also members of Rochester’s Wilmot Cancer Institute. Their key discoveries on how bats prevent cancer:

- Bats and humans have a gene called p53, a tumor-suppressor that can shut down cancer. (Mutations in p53, limiting its ability to act properly, occur in about half of all human cancers.) A species known as the “little brown” bat—found in Rochester and upstate New York—contains two copies of p53 and has elevated p53 activity compared to humans. High levels of p53 in the body can kill cancer cells before they become harmful in a process known as apoptosis. If levels of p53 are too high, however, p53 eliminates too many cells. But bats have an enhanced system that balances apoptosis effectively.

- An enzyme called telomerase is inherently active in bats, which allows their cells to proliferate indefinitely. This is an advantage in aging because it supports tissue regeneration during aging and injury. If cells divide uncontrollably, though, the higher p53 activity in bats compensates and can remove cancerous cells that may arise.

- Bats have an extremely efficient immune system, knocking out multiple deadly pathogens. This also contributes to bats’ anti-cancer abilities by recognizing and wiping out cancer cells, Gorbunova says. As humans age, the immune system slows, and people tend to get more inflammation (in joints and other organs), but bats are good at controlling inflammation. This intricate system allows them to stave off viruses and age-related diseases.

How does bat research apply to humans?

Cancer is a multistage process and requires many “hits” as normal cells transform into malignant cells. Thus, the longer a person or animal lives, the more likely cell mutations occur in combination with external factors (exposures to pollution and poor lifestyle habits, for instance) to promote cancer.

One surprising thing about the bat study, the researchers say, is that bats do not have a natural barrier to cancer. Their cells can transform into cancer with only two “hits”—and yet because bats possess the other robust tumor-suppressor mechanisms, described above, they survive.

Importantly, the authors confirmed that increased activity of the p53 gene is a good defense against cancer by eliminating cancer or slowing its growth. Several anti-cancer drugs already target p53 activity and more are being studied.

Safely increasing the telomerase enzyme might also be a way to apply their findings to humans with cancer, Seluanov adds, but this was not part of the current study.

Gorbunova and Seluanov co-lead the Rochester Aging Research Center at Rochester’s Medical Center. Together, they have built outstanding careers studying the characteristics of long-lived mammals such as naked mole rats and bowhead whales that age well and resist serious diseases.

They also study long-lived humans in collaboration with other institutions, investigating cohorts of people with exceptional longevity to discover which genes and epigenetic factors are overrepresented in these individuals.

The National Institute on Aging supported this research.