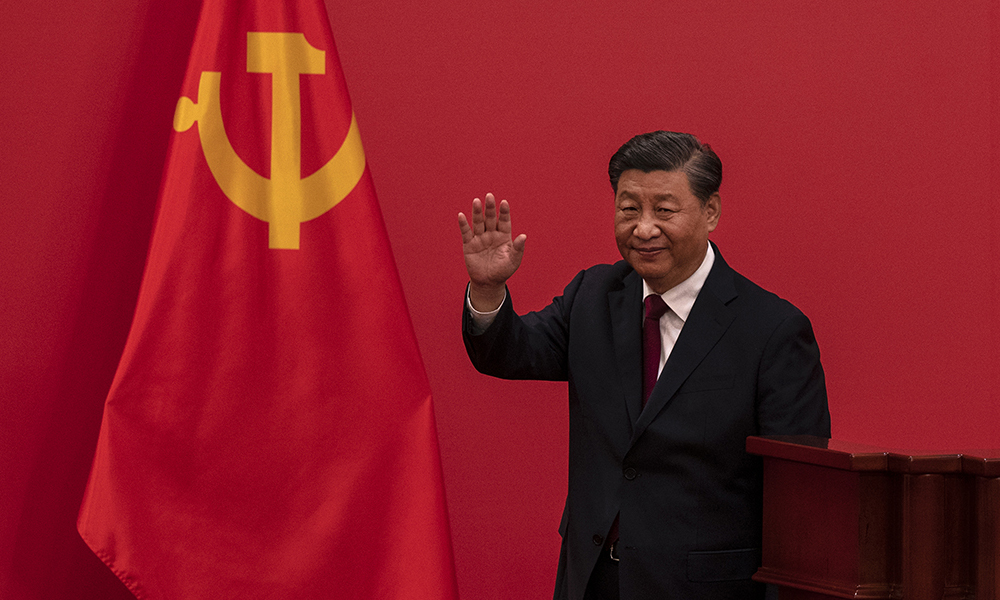

Rochester China expert says Xi Jinping risks blame for China’s mounting problems.

The reappointment of Xi Jinping by the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party to an unprecedented third term as president puts him in the role of leader until at least 2027. Given the problems facing China at present, University of Rochester China expert John Osburg says, “We’re entering a period even more unpredictable than usual.”

Osburg, an anthropologist, is the author of Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality among China’s New Rich (Stanford University Press, 2013), which examines the rise of elite business networks in China and documents the changing values, lifestyles, and consumption habits of China’s new rich and middle classes. That new wealth came about rapidly, following the post-Mao period that began in 1978 known as the Reform and Opening Period. It marked the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in modern history.

Now, however, China is facing a serious slowdown due to COVID restrictions and the reassertion of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) control over the economy. Osburg says people in China are getting tired of the lockdowns and travel restrictions resulting from the country’s zero-COVID policy. If the policies remain in place, Osburg says, “There will likely be a continued economic slowdown, along with growing frustration among ordinary citizens.”

Q&A with John Osburg

How closely does the average person in China follow the events of the Party Congress?

Osburg: It’s hard for the average person to avoid, as coverage of the event saturates the media in China. It isn’t like watching an election in the US, however. The outcome is usually known in advance. China watchers and members of the Chinese elite will be looking to see who is named to top positions as this often indicates shifts in factional power, but ordinary people probably don’t pay that close attention.

Will Xi Jinping now be president for life?

Osburg: This certainly appears to be the most likely scenario going forward barring unforeseen circumstances. In previous decades the successor to the current party secretary was usually known well in advance of a Party Congress. But Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have made no signs of appointing a successor.

How much has China changed under Xi Jinping? How much has it changed in the last five years alone?

Osburg: It has changed quite a bit under Xi Jinping, and especially in the past few years. China-watchers call the period from 1978 up until recently the Reform and Opening Era. During this time, China opened up to the outside world both culturally and economically after 30 years of relative isolation under Mao. Over the course of 40 years, China went from being a poor nation to having the second largest economy in the world, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Chinese students now study in all the top universities in the world, and China is the global center of manufacturing with significant trade ties to just about every country.

But all of this has started to change under Xi. At the start of the reform period, most people assumed that China’s continued social, political, and economic liberalization once begun would be unstoppable. Bill Clinton famously stated that China trying to censor the internet would be like “nailing Jell-O to the wall.” But under Xi, not only is the internet more heavily censored and monitored than a decade ago, Xi also views certain Western ideas as hostile and threatening to (his interpretation of) the tenets of Chinese civilization. In terms of economic reform, for the first time since 1978, after the largest continual economic expansion in modern human history, China’s economy is facing a serious slowdown, largely due to COVID lockdowns and debt problems in the real estate sector, but also partly due to CCP policies which have attempted to reassert state control over the economy.

What should people in China expect over the next five years?

Osburg: The big question is whether or not China abandons or alters their zero-COVID policy. If they don’t, there will likely be a continued economic slowdown, along with growing frustration among ordinary citizens. Lots of people are getting tired of the disruptions brought by this policy, from the lockdowns to not being able to travel abroad. A big component of the CCP’s legitimacy since 1978 has been an implicit bargain that offers citizens constant improvement in their material standard of living in exchange for political acquiescence. Now that the decades-long boom finally seems to be coming to an end, this bargain could be falling apart. Will there be growing anger at the CCP? Will the state attempt to assert even more control over the economy? Will we see opposition to Xi from other political and economic elites? Western observers of China frequently get their predictions about China’s future completely wrong, so I’m hesitant to make a prediction other than to underscore that with Xi beginning an unprecedented third term, the economy in bad shape, and COVID still a wildcard, we’re entering a period even more unpredictable than usual.

Is Xi Jinping’s reappointment an indication of support for him among the populace?

Osburg: Gauging public opinion in China is a difficult task given the very different political and media environment there. I would say that there was considerable support for Xi up until quite recently. The anti-corruption campaign he launched in 2013 was quite popular with ordinary people. In 2020 and 2021, many Chinese were proud of how well their country had managed COVID, especially compared with the US, in which over a million people have died. This all changed with the arrival of the Omicron variant and the growing number of lockdowns. Now people in China see life going back to normal in much of the world while their lives are increasingly disrupted. Lots of businesses are struggling, and youth unemployment is on the rise. The real estate industry is in very bad shape, and local governments have taken on a ton of debt, partly to pay for all the expenses related to covid testing and monitoring. As China’s “Chairman of Everything” Xi’s able to take credit for China’s successes, but his centralization of power puts him at risk of getting blamed for China’s mounting problems.

Is China completely authoritarian, as many outsiders assume, or are there any elements of democracy?

Osburg: China’s system of government is actually more complex than it might seem on the surface. There are no national or provincial level elections in China in which ordinary citizens can participate. In the countryside, there are village-level elections in which residents can choose their village chief, but the CCP sometimes attempts to block undesirable candidates. Local-level representatives are supposed to be elected in cities, but the candidates are pre-selected by the party, and few people participate in the voting process. Higher-level representatives are chosen from the governing body directly below them. Yet, despite not being a democracy, the party-state is very concerned with public opinion. While they almost always censor direct criticism, in some instances they can still be responsive to matters of public concern. Given that they have a centralized, authoritarian system, they can sometimes respond quite quickly and decisively to problems.

Read more

Expect another year of supply chain issues

Expect another year of supply chain issues

Rochester economist George Alessandria explains what is causing the shortages—and why government intervention would be counterproductive.

University links with WeWork to support undergraduates in China

University links with WeWork to support undergraduates in China

The Office for Global Engagement and Center for Education Abroad join with WeWork to provide work and study areas to Rochester undergraduates in China.