There’s an ease about Shaun Nelms ’13W (EdD) as he walks the corridors of East High School. At a commanding height of six foot three, in his navy blue suit and misty pink tie, he’s the face of reform in an institution that went adrift, the calm captain of a ship in rough waters.

When Nelms began his role as school superintendent two years ago, East’s projected graduation rate for 2015–16 hovered at around 20 percent—just one out of every five kids who started as a ninth grader in 2012 was on target to leave with a diploma in June 2016. By 2020, the New York State Education Department would expect the graduation rate to reach 80 percent.

As East navigates toward that distant target, it’s not just the state that’s watching. It’s hopeful East alumni, whom Nelms briefs and leads on tours of the school. It’s the nearby businesses and nonprofits that are contributing time, money, and expertise. It’s the city school district, and the local press corps that’s followed East’s long decline, as well as the emergence of the educational partnership organization—the University of Rochester—that agreed to manage the school, under revamped curricula, renegotiated labor contracts with teachers, and a host of new initiatives, crafted over a yearlong period beginning in the summer of 2014.

It’s now the beginning of year three—and some key numbers have started to move.

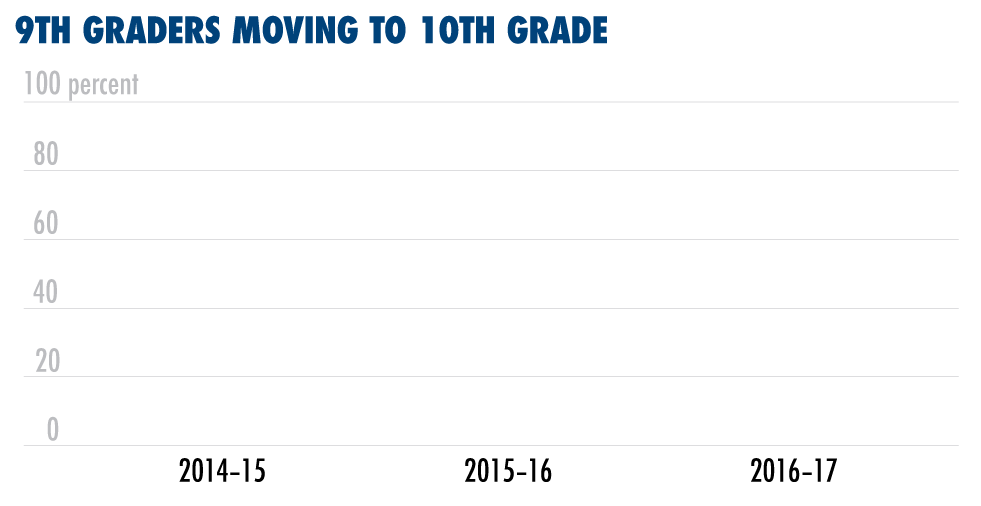

A major predictor of whether any student will graduate from high school is if that student passes the ninth grade. At the end of the 2014–15 school year, fewer than half of East's ninth graders did so. But in both years under the EPO, that number has climbed above 75 percent.

Meanwhile, suspensions and fights have dropped dramatically. More than 90 percent of students reported in a recent survey that they feel safe at East. Families have responded positively to new initiatives designed to support students socially and emotionally.

People who’ve worked at the school for years point to a discernable change in the whole culture and feel of the place. It’s less chaotic, says a social worker. The kids say “hello” more—and leave fewer messes in the cafeteria, a custodian observes. There’s less fighting, says a student. A teacher agrees. He hasn’t had to break one up in while—knock on wood, he says.

There are more bright spots. The partnership has brought expanded offerings and student participation in sports and the arts, and made improvements in culinary and optical programs that combine professional training and experience. The school newspaper, which had gone defunct, is back, under a new name, the Eagle Express. Eighth graders have traveled to Washington, D.C., and sixth graders to Montreal, on field trips that are par for the course in nearby suburban districts, but never before part of the curriculum at East. This past summer, three East High science students watched as NASA’s SpaceX Dragon spacecraft shot off to the International Space Station with their science experiment aboard—one of just 21 projects from high school students in the United States and Canada to receive the honor.

But despite all these achievements, there’s sobering news as well. The graduation rate, among the most important metrics the state uses to measure the effectiveness of its public high schools, is still a hair under 50 percent. It’s just one illustration of how deep the crisis had become at East.

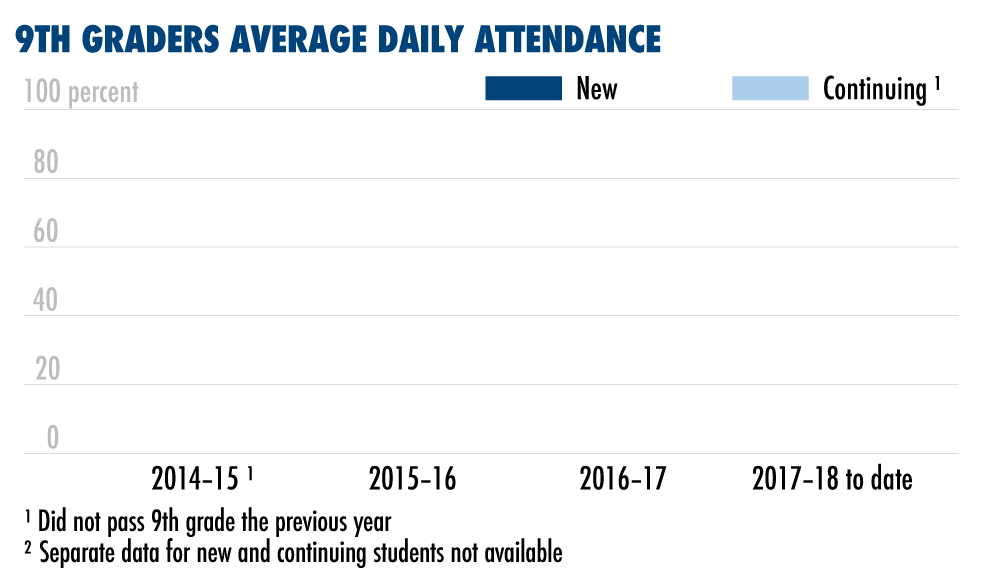

From his office in LeChase Hall, Stephen Uebbing, a professor of educational leadership at the Warner School of Education, watches the progress. Project director of the EPO, he was a key architect of the plan, and served as East superintendent in the first year of the partnership. He's buoyed by some of the progress. He notes, for example, that among the students in regular attendance for the past two years, the graduation rate last spring was closer to 60 percent. On the other hand, he concedes, “This is not risk-free. We can fail. We can fail in other people’s eyes even though we may succeed in our own eyes and in the eyes of the kids and teachers.”

Nonetheless, it’s the kind of project that a small number of universities with top-flight education schools are taking on. Johns Hopkins University has partnered with an East Baltimore K–8 school, now known as Henderson–Hopkins, while the University of California at Los Angeles has joined forces with multiple area schools.

Last spring, the University’s partnership with East attracted the attention of the leading trade publication, the Chronicle of Higher Education. In an interview, University President and CEO Joel Seligman explained the stakes—and why the complex project is so important to undertake. “The key is not to assume this is easy. This is really hard,” he said. But “if you only do safe projects, you don’t advance your communities.”

When you tell people where you work, almost without fail, someone you’re talking with either went to East High School, or knows someone who went to East High School. And nowadays, the first question they ask you is, “How are you guys doing?”

Larry Neal ’75

Chemistry teacher, Upper School

East High School Class of 1971

East High School, 114 years old, has an estimated 20,000 living alumni, and Larry Neal ’75 is one of them. After graduation, an NROTC scholarship enabled him to attend the University, where he studied chemistry. Since 1998, he’s been a chemistry teacher at East.

Neal served in the Navy for 20 years in roles that included flying planes off aircraft carriers. He shares the story with his students. “I’ve got a couple of videos I show them,” he says. “I tell them, ‘I used to do this.’ And they say, ‘whoa.’?” Neal also works in stories of his days delivering newspapers and working at a local grocer, the Star Market. “I kind of show them the arc of my life, so they know I came from someplace.”

After a brief stint in the private sector, he left his job, following some advice from his chemistry teacher at East, Jean Slattery ’74W (EdD), who had long before planted the idea in his mind of teaching in Rochester city schools. He sold his home in Virginia Beach and moved to Rochester so he could pursue his “sole objective of teaching at East High School.”

This kind of devotion to the school is not unusual, says Neal, whose siblings and in-laws all went to East, and whose son, Jeffrey, has started there as a teaching assistant this year. Rebecca Laske, a counselor in the Lower School, tells a similar story. One of six siblings, all of whom went to East, she graduated in 2005. Her brother, Paul Conrow, who graduated in 1995, now teaches science and directs the precision optics program at the school. “I’ve always been proud of where I went to school,” she says. “There have always been a lot of positive things going on in this building, back from when I was a student.”

Stories vary about exactly when it started, but at some point, this bedrock institution began to crumble. Over time, the Rochester City School District got a lot poorer. Middle-class “white flight” to the suburbs, which began decades ago, accelerated, while more recently, middle-class African-American and Puerto Rican flight have piled onto the district’s challenges. East is now the largest school in a district with a child poverty rate nearing 50 percent, which makes the Rochester City School District’s population the second poorest of any district’s in the nation, surpassed only by Detroit.

Laske notes that while city high schools such as the School of the Arts and the Joseph Wilson Magnet School have selection criteria, East has been—and remains—an open school. That won’t change under the partnership. “All you have to do is sign up, show up,” says Uebbing. “There’s no minimal score. You don’t have to have a clean record with the law.”

East reached a crisis point in March 2014, when the state’s education department, citing persistently low academic performance, issued an ultimatum to East that included the options of a phase out or closure. In response, the president of the city school board approached Warner School Dean Raffaella Borasi as well as Seligman about forming a partnership to manage East.

Uebbing says it’s an important point that the initiative came from the school board. Occasionally, a media outlet, or someone in conversation, will refer to the partnership as the University’s “take over” of East. It’s a linguistic shortcut that misrepresents the relationship that Warner School leaders worked hard to establish. Following the state’s approval of the partnership in the summer of 2014, a team of Warner School faculty members spent months conducting meetings and focus groups with teachers, parents, students, and others most closely involved with daily life at East. Those conversations were followed by sweeping changes, including a longer school day, overhauled curricula, a new approach to student discipline, mandated professional development for teachers, and a new collaborative approach to instruction. Partnership leaders also renegotiated contracts with three separate unions to account for the added work and responsibilities, requested a new budget from the district and state, and required in early 2015 that all staff members who wanted to continue to work at the school reapply for their jobs, promising commitment to a new motto, “All in, all the time.”

As an effort under pressure to show dramatic results, according to a predetermined set of measures, the partnership might easily have focused narrowly on enhancing academic supports. Those are important components, but the plan is much broader than that. It includes new measures to help students develop social and emotional skills, and practices designed to build strong relationships between and among teachers, students, school leaders, and families. It seeks, above all, a cultural transformation in which stakeholders achieve a sense of ownership in their relationship to the school. The idea is that for academic achievement to take place, there has to be an environment to support it.

People say, “So how’s East, what do you think of East?” And I’m always like, “I’m optimistic; I’m optimistic for so many reasons.” For me, personally, I live right down the street. These are our kids. If they’re not in school, and they’re out in the streets making bad choices, they’re on our streets. They’re in our community.

Michelle Garcia, LCSW

Lower School Social Worker

East isn’t a neighborhood school in the traditional sense, and hasn’t been since 2002, when the city school district adopted a choice model, allowing students and parents to apply to schools throughout the city. Most students at East don’t live in the Beechwood neighborhood that abuts the school’s sprawling building at the corner of East Main Street and Culver Road.

Neighborhood residents like Michelle Garcia, a Lower School social worker at East, hope that as the school makes progress, more kids from the neighborhood will seek to go to East, strengthening burgeoning ties between the school and its environs, expanding the community of stakeholders ready to go “all in” for East.

Garcia has been a social worker at East for five years, and elsewhere in the district for six years before that. Among her specialties is trauma-related counseling.

High numbers of students at East Lower and well as Upper School have experienced traumatic events. Since the partnership began, she’s seen a significant expansion in the staff of counselors and social workers.

“The staff and students always wanted to be successful, but the barriers to that success were immense,” she says, referring to her years at the school prior to the EPO.

Garcia cites a change in climate that she credits, in large part, to two major initiatives brought about by the partnership. One is an approach to discipline called restorative practices.

In contrast to more traditional methods of discipline, it recognizes that bad behavior—fighting, verbal abuse, and other forms of disrespect that can take place in a school setting—often happen because kids don’t have the skills to handle conflict in other ways. They also may not have formed relationships with the people around them that are conducive to building mutual respect.

When a conflict occurs between students at East, they’ll sit together, sometimes in Garcia’s office. “There’s a series of questions that we ask,” says Garcia, describing the facilitation that she and other adults at East initiate with the students. “What happened? What were you thinking and feeling at the time? What are you thinking and feeling now? Who was affected, and what needs to happen to make things right?” When adults take this approach, “kids often times will find the solutions themselves, as opposed to adults finding the solutions for them.”

The restorative practices approach is not new, and many schools and institutions have adopted it, says Laske, who works alongside Garcia as a counselor in the Lower School. She used it in her previous job as a K–8 counselor at the Urban Choice Charter School in Rochester. But under the partnership at East, in accordance with the school motto “All in, all the time,” every staff member has been trained in it, and Laske says that makes a big difference. There’s a consistency in the way that adults in the building address problems as they see them arise. “Kids pick up on that,” she says. “We’re modeling for them all the time.”

Nelms says the use of restorative practices is a means “to create a safe space for dissent to occur.” And students have taken advantage of it. He’s had students approach him to tell them they’re going to be in a fight—and they don’t want to fight. Students have taken to giving teachers a heads-up if they think some of their peers may be brewing for a fight. And those teachers, now trained in restorative practices, are equipped to help diffuse tensions, and steer students toward more productive ways of addressing disputes. The effects have been dramatic, as the numbers of fights in the Upper School, as well as suspensions, have plummeted.

Working in tandem with restorative practices is a second initiative, the family group. Every student at East is assigned to one. Family groups are groups of around 10 students who meet daily with their “carents”—a pair of teachers or staff who relate to the group as “caring parents.” For students who may have few caring adults in their lives, the group is designed to provide consistent social and emotional support in a quasi-family structure. For those students who don’t lack for caring adults in their lives, the group is an important means of finding a place among the nearly 1,300 students bused to the school from all over the city.

Family groups are composed so that, ideally, all students will find in them some comfort of the familiar, but also some reflection of the diversity of the student body.

Sofia Gazali, a senior who came to East last year, says in family group “we talk about different subjects—everything.” At her previous school, Gazali, a Muslim, says some of the students would make fun of her headscarf. But it hasn’t happened at East, something she attributes in part to the climate established through family groups. There have been other benefits. Although family groups aren’t designed to offer academic support directly, carents are attentive to students’ academic progress, and Gazali, who is applying to colleges this year, says her carents have provided her helpful advice on her applications.

For students less focused than Gazali, the family group is one more means through which adults and peers can deliver a collective message—that they’re important, their futures are important, and there’s a community right there that wants them to succeed.

As a ninth grader, I really made a big change... I had a lot of people telling me that ninth grade was a very important year. I didn’t really take [school] as seriously until I actually made it to ninth grade. They told me that if I didn’t have certain credits, I wouldn’t make it to the 10th. And I knew that I didn’t focus, which is why I stopped surrounding myself with negative people.

Nashalie Guzman

10th grader

When Nashalie Guzman started at East as a seventh grader, “there were a lot of fights,” she says. And “a lot of drama, constantly.” She allowed herself to get drawn in. And then, last year, as a student in the Freshman Academy, she changed her attitude. “Now I have a lot of people who look up to me, they ask me for help,” she says.

Created under the EPO, the academy surrounds ninth graders with intensive support. Academy classrooms occupy their own wing of the sprawling school building, keeping older students, for the most part, at a distance.

While the criteria for moving from one grade to the next include parental discretion in the lower grades, that changes once students reach the ninth grade. In order to advance to 10th, students must pass five classes. Among the classes ninth graders typically take are Algebra and Global History, and in New York State, students are required to pass statewide regents exams in both subjects in order to graduate. These exams, which constitute two of the five regents exams required in New York State, are considered by many teachers among the steepest hurdles to high school graduation.

Leda Williams-Matthews ’88, ’89W (MS) has been teaching social studies at East High since 1989, and she teaches Global History in the Freshman Academy. She’s among the educators who’ve long known that there’s a big developmental gap between kids ages 14 and 15, and kids ages 16. “Many students come into the ninth grade without the habits and skills they need to have,” she says.

That’s true of ninth graders from highly educated, affluent families as well, who often arrive in high school with nascent organizational skills and a high level of distractibility. But those traits have deeper consequences for many students at East, who often arrive at high school lacking the reading and writing skills that Williams-Matthews says are critical to passing the Global History regents exam, and the foundational math skills that her colleagues in the math department say are equally essential to the Algebra exam.

The EPO has taken a number of steps to address the problem. The addition of sixth grade to the Lower School allowed teachers at East an extra year under the new model to work with students on basic skills. Support periods were added to students’ schedules, taking place in designated rooms staffed by people like Nicole Bak, a special education teacher with multiple certifications, as well as a doctorate in educational psychology. In year one, says Bak, who works mainly with the Freshman Academy, she had one room.

Halfway through that year, she got a second room. Now, in year three, she circulates through three rooms, adjoined by a narrow hallway, where she, two other support teachers, a literacy consultant, and a group of volunteers, provide homework help, test preparation, practice in foundational skills, and track the overall progress of each student.

“Kids actually want homework, oddly enough,” says Bak, who fielded many requests for homework in the first weeks of the school year. “I think part of the reason is that we’ve created this environment where they can come and get help, and so it’s not piling up.”

Williams-Matthews says the support rooms and other new resources have provided much of what teachers have long said they'd need to help their students achieve state benchmarks. “In years past, it was always about not having the supports that we needed to have our kids be successful,” she says. “They needed more counselors, more social workers, more teachers. Now we have it all.”

Still, it will require teachers like Williams-Matthews to be “all in, all the time,” to continue the dramatic improvements that have taken place in the Freshman Academy. Raised in Syracuse and the self-described product of urban schools, she says she made it to the University because of the teachers and family members who made it clear that “great things were expected of Leda.” As she moves about her classroom of 10th-grade Global History students—the ones who didn’t pass the class the first time around—she has one message to deliver. “I get it. Life can get tough. But they must believe that their circumstances can change, and will change, if they’re willing to work hard. And consistently work hard.”

Every step of the way, we keep asking ourselves, how can we make a school that’s failing better?

Shaun Nelms ’13W (EdD)

Superintendent,

East Upper and Lower Schools

There’s been little about the work at East that’s been written in stone. The partnership has functioned like an ongoing conversation with a simple ground rule: that the topic is how to improve the lives of students at East, and no one gets to deviate from it.

The conversation hasn’t always been simple or easy. “We worked hard to give teachers a voice, give students a voice, and give staff a voice, in ways that surfaced the real issues,” Nelms says. “After year one, we made a ton of changes based on those recommendations.”

In the second year, Nelms presided over the evolution of a leadership structure that placed significant authority in faculty identified as teacher leaders. And while he’s highly visible about the school, the Upper and Lower Schools each have principals who serve as the building leaders. In a climate survey conducted by an outside organization last spring, more than 90 percent of faculty respondents reported trust in their building leader and confidence that their leaders cared about them and the challenges they faced. At the close of year two, Nelms declared East “a school that they now call their own.”

Mutual trust will continue to be important, as these partners are together for the long haul. Although the EPO is technically a five-year plan, it’s likely that it will take longer than that for East to reach all the key benchmarks the state has set.

Nelms won’t venture any predictions about where many of the metrics will land, either at the end of this year, or at the end of the five-year period. But he’s watched as students in the lower grades have come up through the school, and are now reaching the upper grades. “I love when teachers who now are receiving these students are saying, man, these kids can really write,” he says. “Or these kinds think very differently. Or these kids are causing me to plan lessons much differently than I did in the past. That excites us.”

Read more about the University's community collaborations

Read more about the University's community collaborations

Students say the atmosphere at Rochester's East High School two years ago was "a hot mess" and disrespect was rampant. That's when the University of Rochester entered into an educational partnership with East High and began working to change the culture in the struggling school threatened by closure.

Professor Joanne Larson is part of the leadership team for the educational partnership organization (EPO) between the University of Rochester and East High School. She says the prospect of helping turn around a school that was struggling with inadequate performance was one of the hardest things she's ever done.

A Department of Biology initiative introduces East High students to fruit flies -- and the excitement of science.

The School of Nursing provides free medical care to East High and other students in the Rochester city schools.

The SMILEmobile -- the Eastman Institute for Oral Health's dental office on wheels -- brings dental care to East High.

A Rochester program helps provide free glasses to students in Rochester city schools.