Beal ’85E and his wife, Joan Beal ‘84E established the Beal Institute for Film Music and Contemporary Media at the Eastman School of Music in 2015. Beal’s composition “The Pathway” premiered at the inauguration.

The Inauguration of

The University’s Eleventh President

On October 4, the University celebrated the inauguration of Sarah C. Mangelsdorf as Rochester’s 11th president with a ceremony in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theater.

Beal ’85E and his wife, Joan Beal ‘84E established the Beal Institute for Film Music and Contemporary Media at the Eastman School of Music in 2015. Beal’s composition “The Pathway” premiered at the inauguration.

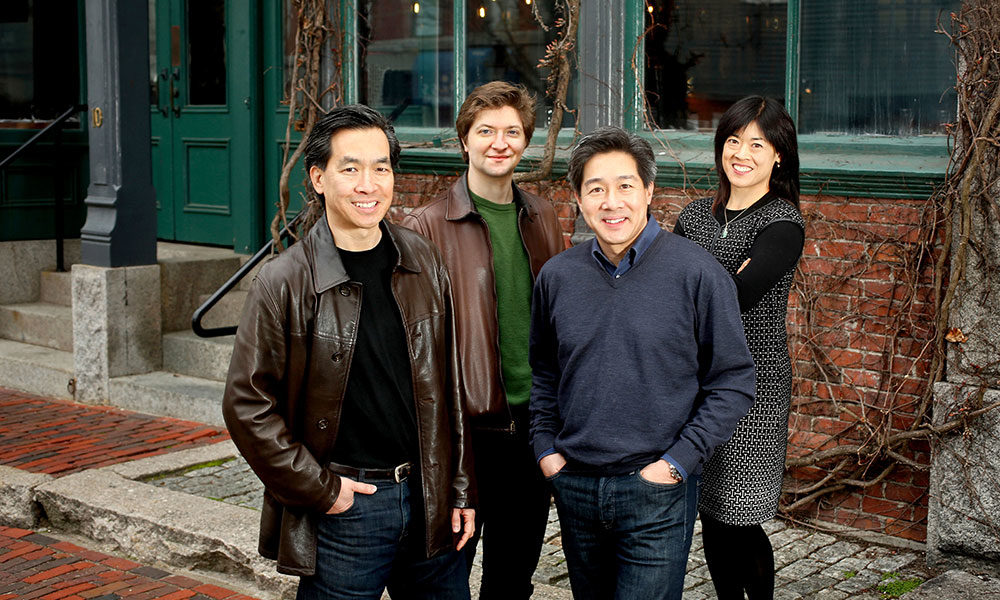

The Ying Quartet is the string quartet-in-residence of the Eastman School of Music. The ensemble formed at Eastman in 1988 and includes original members (and siblings) cellist David Ying ’92E (DMA), violinist Janet Ying ’93E, and violist Philip Ying ’91E, ’92E (MM), as well as violinist Robin Scott, who joined the ensemble in 2015.

The musical centerpiece at the inauguration of President Sarah C. Mangelsdorf on October 4 is a work by one of the contemporary masters of musical storytelling, Jeff Beal ’85E. The Eastman School of Music’s internationally recognized Ying Quartet performed the piece.

The University mace, newly engraved with the name of Sarah C. Mangelsdorf, was handed to the 11th president at her inauguration ceremony on October 4.

For generations, three ritual objects—the University mace, charter, and seal—have been the centerpiece of the presidential inaugural ceremony. Across many decades, these same insignia have invested authority in presidents with wide-ranging leadership styles, each of whom has also shaped their own ceremony—as President Mangelsdorf did with hers on October 4.

If you have questions about the inauguration, please email Inauguration@rochester.edu or call (585) 275-3297.