Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank says distrust jeopardizes the country’s future as an economic powerhouse.

When University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank was five years old, he found his father’s pulp science fiction magazines featuring pictures of bug-eyed monsters and lunar landscapes. That was the beginning of Frank’s love affair with the stars and science itself.

“For me, it was a quasi-spiritual thing,” says Frank. “I felt this powerful sense of awe and sacredness about the vast sky, and the fact that I was just one story out of an infinity of stories.”

Frank wishes everyone could look at science with the same kind of awe and wonder. But given the public’s growing distrust of scientists, he knows that’s a tall order, one with economic ramifications.

“The nation that controls the scientific high ground controls the future,” says Frank, who’s confident that the public’s faith in science will make a comeback—but it will take time.

Q&A with Adam Frank

What does it mean to be a scientist?

Frank: People go into science because they have intense curiosity. Every kid is basically a scientist; they like to poke things to see what happens. Fortunately, we can turn that curiosity into a lifetime’s work. If you loved watching ants as a kid, you become an entomologist. If you loved staring at the stars, you become an astronomer. Being a scientist also means being an engineer who likes to build things to see if they work. A scientist is just a person who’s willing to stay with a question for hours, days, weeks, or years. You go to sleep at night and can’t wait to wake up and get back to the problem you’re working on.

So, what appeals to you most? The question, the search for an answer, or the answer itself?

Frank: No matter what answer I get, I just go on to the next question, so it’s the inquiry—the absorption in the question—that matters. When I work on a mathematical derivation, I’ll put my head down and get started, then suddenly five hours have gone by and I didn’t notice at all. You just disappear into the work. I think the same happens with musicians and artists. And there’s this sense, especially with the deeper questions, that something extraordinary is waiting to be seen just over the horizon. So for me, it’s the journey that is so engaging.

What are the biggest misconceptions that people have about science and scientists?

Frank: I remember seeing a poll a couple of years ago that showed the public trusted scientists more than they trusted people in other professions. But in the same poll, the public said scientists don’t have feelings like other people do. They apparently got that notion from watching TV shows where scientists were portrayed like Mr. Spock on Star Trek. That, of course, is the biggest misconception. Scientists fall in love, we get pumped when our baseball teams win (the Mets, thank you very much), we’d throw ourselves in front of a bus to help our kids—there’s fundamentally no difference between a scientist and anyone else.

According to a Pew Research Center survey released in February 2022, the American public’s trust in scientists has dropped significantly in the last couple of years. What do you think accounts for that?

Frank: A lot of it has to do with the COVID pandemic. Because the data were new and constantly changing, the scientists couldn’t always get it right in the beginning. But then, very quickly, they figured it out, which is why we had a vaccine in less than a year. On top of that, the pandemic became politically polarized, with experts like Dr. Fauci being villainized. Also some very well-funded people have been leading efforts for years to subvert the public’s understanding of science. This is particularly true of climate science since it threatens the bank accounts of folks in the oil and coal industries. But sowing distrust in science is a very dangerous and slippery slope. You can’t just point to one area of science and call it a hoax. It will spill over into other areas of science. And the problem with that is that science is a central pillar of this country’s success. Now all this misinformation and science denial is being spread for purely political ends, and we’re going to pay a real price for that if we don’t correct it.

Some science skeptics cast doubts on the COVID vaccine because it seemed to have been developed too quickly. How do you respond to that concern?

Frank: The problem is they don’t understand that the technologies behind those new vaccines had been in the works for years because of government-funded research. We were lucky that these developing biotechnologies were easily turned into COVID vaccines. The problem is most people don’t understand how research works, how scientists as a community work together for years to establish what they know and what they don’t know.

What do people need to understand about the process of scientific research?

Frank: More than being able to quote the facts of science, what we really need is for people to understand its methods. I like to talk about the 3 “S’s” of science: spitballs, supertankers, and stadiums. Let’s take the question, “Is coffee bad for you?” Every other day you hear news of a research study showing it is bad for you or, no wait, it’s actually good for you. But every research paper is just a little spitball that’s being shot at the supertanker of science. It takes a supertanker seven miles to turn around. That means all those spitballs have to line up on the same side to make the supertanker change course. In other words, any individual research study doesn’t mean much by itself. Finally, who’s steering the science supertanker? Everybody!—a stadium’s worth of scientists. A consensus has to develop in the scientific community before you can say science “knows” something. What does this tell us about coffee and health? It tells us science doesn’t know yet. When you see all those reports going both ways it tells you the science isn’t decided. This is the opposite of something like climate change where all the studies have been saying the same thing for, like, 30 years. When scientists argue, it’s over things at the edge of research—over questions that have not yet been resolved. It takes time to resolve those kinds of questions.

What is the price that we pay for science misinformation?

Frank: The implications are very simple. The nation that controls the scientific high ground controls the future. Germany before World War II was a scientific powerhouse. It is, after all, the birthplace of quantum mechanics. With the Nazis, it was clear that the nation was moving toward authoritarianism and much of their scientific talent left for the United States. So if the United States continues down this road of science denial, the best and brightest of the world won’t come here. It’s really about our nation’s capacity to be an economic powerhouse.

What’s the best way to gain the trust of the skeptics?

Frank: I think they need to understand how science works. We don’t gain their trust just by telling them about results. They need to understand how scientists know what they know. Skeptics should also be encouraged to imagine life without science. They should think about the robotic hip replacement that allows their grandma to walk around again. It’s not like a special version of science is used to study climate and another used to make hip replacements; it’s the same science. The same process is used in the research that leads to medical devices, cell phones, computers, vaccines, and climate understanding.

It seems that the science deniers have been able to make effective use of social media and sound bites. How can you counteract that?

Frank: Maybe over time, we’ll become savvy media consumers, but right now we’re just in the grips of insanity.

But there’s one more problem which is even deeper. People used to be humble about their ignorance. I’m ignorant about many things, but I’m not going to parade that around. If I don’t know something, I’ll admit it. But somehow, we’ve gotten to a point where ignorance has become a hallmark of pride. And that’s a social matter. You wouldn’t want to fly in a plane piloted by a knucklehead who had no experience but was blowing off steam about how “he didn’t need experts telling him what to do.”

Are you hopeful?

Frank: I’m always hopeful, because what’s the alternative? But we may be in for a rough time for the next few decades as we try to sort this out. There are people gaining advantages both economically and politically from all the polarization, and they’re throwing science into the mix. Those are the forces that are going to take time to work out.

Astrophysicist Adam Frank

A self-described “evangelist of science,” Frank regularly writes and speaks about subjects like intelligent life forms in the universe, high-energy-density physics, space exploration and missions, climate change, and more.

Read more

Using data science to tell which of these people is lying

Using data science to tell which of these people is lying

Rochester researchers used data science to analyze more than 1 million facial expressions to more accurately detect deception based on a smile.

Genetically modified food: Would you eat it if you understood the science behind it?

Genetically modified food: Would you eat it if you understood the science behind it?

The short answer is “yes,” according to researchers who set out to discover whether more information about genetically modified foods could change consumers’ attitudes.

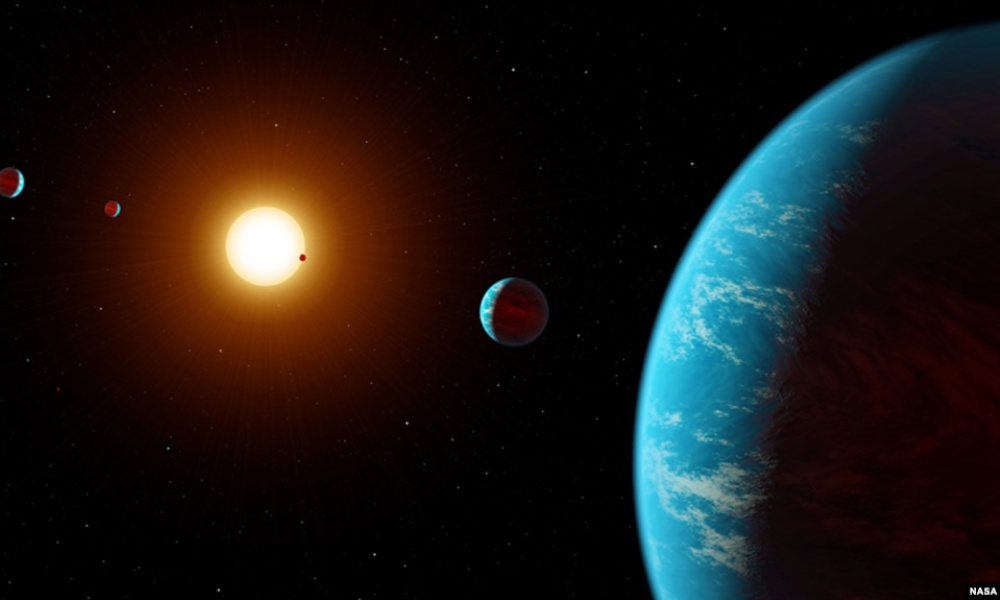

Are aliens real? Do aliens exist? Technosignatures may hold new clues

Are aliens real? Do aliens exist? Technosignatures may hold new clues

Adam Frank is searching for “technosignatures,” or the physical and chemical traces of advanced civilizations, among the 4,000 or so exoplanets scientists have found so far.