When Joanne Bernardi, associate professor of Japanese, was an undergraduate pursuing a degree in photography and film at the Kansas City Art Institute in the mid 1970s, she entered a national photography competition. It required her to say what she would do with the money if she won. She had recently seen some acclaimed Japanese movies, such as Rashomon and Ikiru, and was taking classes in Japanese literature and history — so she wrote that she would visit Japan.

“Then I got the money, and I had to go,” she says jokingly.

It was a transformative visit, spurring her decades-long interest in uncovering a side of Japan that few Westerners knew about — a cosmopolitan, modernizing nation that was already making its mark in film and experiencing a boom in tourism well before World War II.

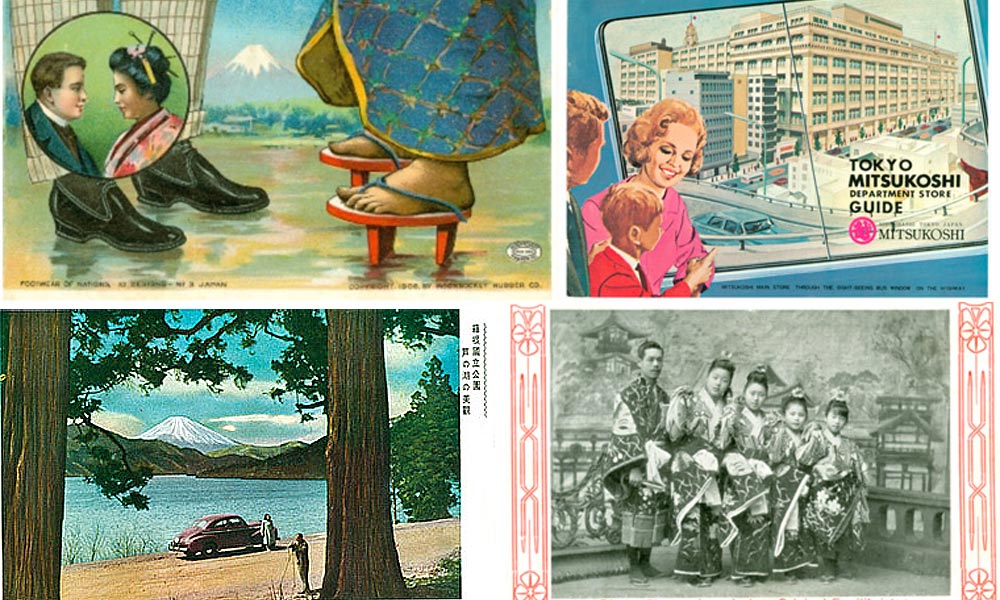

Bernardi has documented this with hundreds of early 20th century postcards, films, brochures, advertisements and other objects now on display at an interactive online archive and research project developed with the help of the Digital Humanities Center. “Re-envisioning Japan: Japan as Destination in 20th Century Visual and Material Culture” uses travel, education, and the production and exchange of images and objects as a “lens to investigate changing representations of Japan and its place in the world in the first half of the 20th Century.”

For example, Bernardi uses the material in a University course she teaches called Tourist Japan, in which tourism and tourist culture is used to illuminate “endless ideas, problems, and questions about the relationship between modernization processes and identity formation.” Bernardi hopes her project will also be an interactive resource for other scholars.

“What a lot of people have in their minds about prewar Japan is rising fascism,” Bernardi notes. “And yes, there was that. But there was also a very vibrant popular culture.

“What a lot of people have in their minds about prewar Japan is rising fascism,” Bernardi notes. “And yes, there was that. But there was also a very vibrant popular culture.

“There’s been this assumption, for example, that everything significant in the Japanese film industry happens after the Second World War. There were a lot of articles written about how Americans started the Japanese film industry then because we introduced them to Hollywood movies. That’s not true at all.”

Japan’s thriving film industry, dating back to the silent era, had become one of the world’s largest by the 1930s, Bernardi discovered during two subsequent, extended stays in Japan to do her dissertation research and to teach as an associate professor at Ibaraki University. Moreover, Japan was already very familiar with Hollywood movies, which sometimes made their way to Japan because they were shown on ships bringing American tourists to the country before the war.

“People often assume Japan before the war was pretty inaccessible,” Bernardi said. “But it was very much on the international map.”

The modernization of Japan “is a really interesting topic,” Bernardi adds. “It’s always been conflated with westernization, but that really doesn’t tell the whole story. There’s always been a modernization trend in Japan that’s really its own, based on indigenous forms of transformation. The war created a kind of artificial point in history; it’s taken a long time, but people are now able to see more continuities between post-war and pre-war Japan than they were able to before.”

Digital Humanities “unleashes collection’s potential to make meaning”

For the last 15 years, Bernardi has been on a mission. She’s been collecting postcards, brochures, films and other visual representations of early 20th century Japan — often at her own expense — as part of scholarship investigating representations of Japan and its place in the first half of the 20th century.

But her very success — her collection now includes several hundred postcards and more than 1,150 film prints, brochures and other objects — posed a dilemma: How to present all this in a way that would allow the collection to grow AND would allow other scholars to register and contribute content, “creating a dynamic community of users who can share ideas and related research”?

“I knew all along I would have a problem with a book manuscript,” Bernardi said, noting that the cost of color reprints alone would be prohibitive. “So a web presence seemed like the way to go.”

“I knew all along I would have a problem with a book manuscript,” Bernardi said, noting that the cost of color reprints alone would be prohibitive. “So a web presence seemed like the way to go.”

She approached Nora Dimmock (currently assistant dean for IT, research, and digital scholarship, who was then directing the Multimedia Center),assuming that the design and launching of a web presence would require a lot of Bernardi’s time and expense, and was stunned when Dimmock replied: “We’ll do it for you.”

“I thought: ‘Oh my god,’ ” Bernardi recalled. “They (Digital Humanities Center) have been with the project from the beginning in terms of getting on the web.”

“They’ve helped me develop the site, and think of ways in which the material will be best presented, ways which make the most of its meaning, and ways that will enable viewers to access the material and further scholarship and teaching in this area.”

“This was a huge turning point in the project. In turning this project into an online archive, digital technology acted as the catalyst, unleashing my collection’s potential to make meaning.”

The Digital Humanities Center applied for and received a Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) Postdoctoral Fellow award for 2015-2016, which will help migrate the site to an Omeka platform that is more conducive to community interaction. In the meantime, Bernardi is also grateful for a PumpPrimer II award from the Arts, Sciences and Engineering Dean’s office in April that enabled her to digitize film prints and hire musicians to record the sheet music in her collection.

She now has the perfect tool to continue her research and publish her scholarship. “There are so many areas I can investigate just within this one project. I am very happy to continue with this forever.”