University of Rochester music theorist explores the interrelationship between poetry, lyrics, and music.

Reading the opening lines of Van Morrison’s “Into the Mystic,” Matt BaileyShea, an associate professor of music theory at the University of Rochester, notes that “the song is widely viewed as a classic and a great song. However, it is not great poetry.”

Concurring in that view is Morrison himself. When Rolling Stone magazine interviewed him for a 1978 article about the lyrics, he suggested people take them too seriously, and the words might even be “irrelevant.”

We were born before the wind

Also, younger than the sun

‘Ere the bonnie boat was won

As we sailed into the mystic.

Someone studying Morrison’s songs could be convinced they should overlook the lyrics to focus on other elements, like harmony, texture, vocal timbre, rhythm, and meter. But BaileyShea shows in his new book that with close attention, there is a great deal to savor in Morrison’s words.

In the book, Lines and Lyrics: An Introduction to Poetry and Song (Yale University Press 2021), BaileyShea takes a basic understanding of poetry to explore and draw attention to words, and the sounds of the language to get a deeper interpretation of songs from a wide variety of music styles, from hip-hop to rock to art songs. The goal of the book, he says, is “to get people thinking more carefully about the subtle, sophisticated details of song lyrics, especially in how they relate to the music.”

BaileyShea has been teaching music theory in both the Arthur Satz Department of Music and the Eastman School of Music since 2003. The relationship between poetic texts and their musical settings has long been a focus for BaileyShea, who organized a symposium for the University’s Humanities Center to explore the topic. The interdisciplinary gathering engaged scholars from the Eastman School, the Department of English, and the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures.

Q&A with Matt BaileyShea

When did you first start thinking about the connection between poetry and song lyrics?

When did you first start thinking about the connection between poetry and song lyrics?

BaileyShea: I’ve been studying vocal music for decades, but about 10 years ago I began thinking more seriously about the question “Who sings to whom?” in song. I was recognizing that songs often shift pronouns in ways that make this question a bit complicated—“he” becomes “I” becomes “you,” and so forth. I asked [the Joseph Henry Gilmore Professor of English and renowned poet] Jim Longenbach for some help with this and he graciously agreed to meet with me. He gave me excellent advice about lyric poetry in general, and I eventually sat in on one of his poetry courses, which was especially eye-opening. It really changed the way I think about poetry and song. The book mainly emerged from those early discussions with him.

There’s an ongoing debate about whether song lyrics should be treated as poetry. You’re interested in both song lyrics and poetry, but are not especially interested in this debate. Why not?

BaileyShea: In most cases, song lyrics are conceived and written in lines, using rhymes, metaphors, imagery, and much else that we often find in poetry. Pop songwriters don’t usually intend to have people read them aloud as if they were poems—it would usually sound silly if we did—but we can certainly benefit from thinking about the poetic elements of a song. That’s the main goal of my book: to get people thinking more carefully about the subtle, sophisticated details of song lyrics, especially in how they relate to the music.

Yet Bob Dylan was a recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, and we often see written collections of lyrics by people like Leonard Cohen, Jay-Z, or Kurt Cobain. Do you think it makes sense to see certain lyricists as great poets?

BaileyShea: Personally, when I want to read poems, I’d rather pick up a book by a contemporary poet like Terrance Hayes. When I want to experience lyrics—whether by Joni Mitchell or Jay-Z—I’d rather listen to the songs. That’s the thing about lyrics; they must work well with music. Also, I think we get caught up too often in silly stereotypes about artistic value. People sometimes suggest that calling a songwriter a “great poet” is the ultimate compliment. The implication is that writing song lyrics is inherently inferior to writing poetry. But why? They’re both very hard to do well.

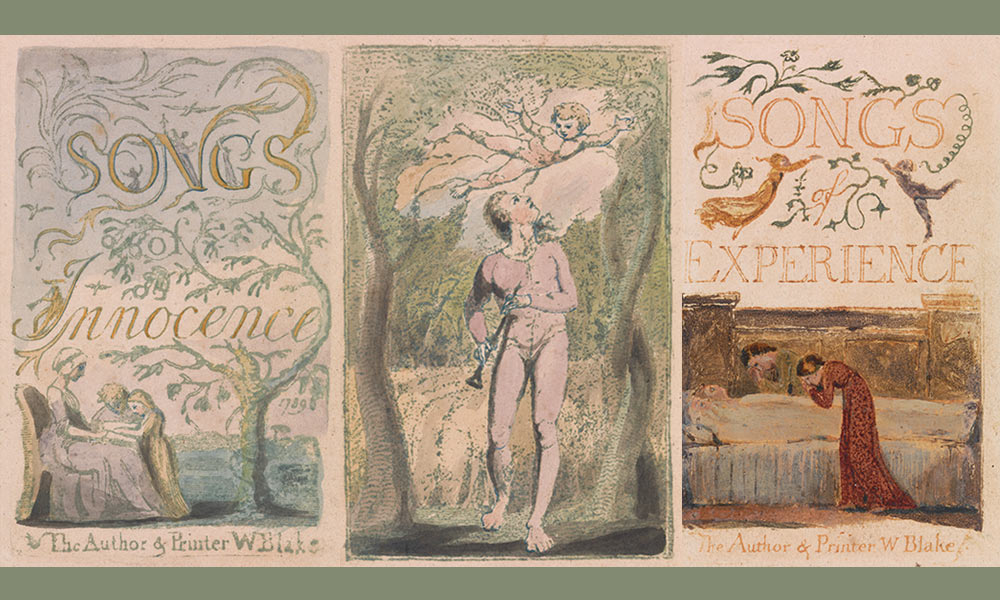

Throughout your book, you engage your readers in discussions of songwriters and musicians that span a range of musical styles, such as Kendrick Lamar, Patti Smith, Benjamin Britten, and Björk. You also look at poetry by people like Anne Sexton, Robert Frost, and William Blake. Was there difficulty in choosing which works and artists to focus on? What was the process like?

BaileyShea: I mostly drew from poetry and songs that I was listening to at the time. I have relatively broad tastes, so the playlist for the book ends up looking somewhat haphazard. But I think it’s a good thing. Most readers will probably recognize a least a few songs and poems that they already know and enjoy. And the diversity of repertoire is crucial for another reason: it allows us to identify similar patterns and strategies across a wide range of texts.

What do you want readers to gain from your work?

BaileyShea: I mostly just hope the book makes people enjoy reading poetry and listening to songs more than they already do. I imagine many of my readers will be coming at this from either the poetry side or the music side. Hopefully it helps poetry fans listen more closely to lyrics. And hopefully it makes musicians into fans of poetry.

Read more

William Blake has left fingerprints all over pop culture

William Blake has left fingerprints all over pop culture

The Romantic-era poet’s influence pervades modern writing, music, film and TV. The University’s William Blake Archive has digitized nearly 7,000 images from Blake’s creations, making them accessible to scholars and fans alike.

We rely on words to carry out even the most mundane acts of communication. Those same words are poets’ medium of creation. In How Poems Get Made, James Longenbach asks how poets turn bare utterance into art.

Teaching the complexities of the Nobel Prize in Literature

Teaching the complexities of the Nobel Prize in Literature

English professor Bette London introduces students to Nobel-winning authors and the controversies surrounding the prize.

How do you make a poem?

How do you make a poem?