Children diagnosed with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD)—caused by prenatal alcohol exposure—often face lifelong developmental, cognitive and behavioral problems. Without the right support they are at high risk of mental health disorders and other life problems. Affecting around 2 to 5 percent of school-aged children in the United States, FASD is a major public health problem.

But children with FASD are not the only ones who struggle; often their parents and caretakers do, too. What can make the job of parenting a child with the disorder especially hard is the general lack of awareness surrounding FASD, and the dearth of available resources and specialists.

Unsurprisingly, these barriers contribute to the already high stress levels that go hand-in-hand with parenting a child with disabilities. Stress, of course, can have a direct bearing on family cohesion, as well as the caregivers’ mental and physical health. That’s why, according to experts, self-care for parents is a critical resource.

A new study by a team of University of Rochester researchers, published in the journal Research in Developmental Disabilities, examines how FASD caregivers’ perceived confidence in and the frequency of self-care is related to stress, parenting attitudes, and family needs.

“We know that parents who are stressed tend to feel less effective and less satisfied as a parent,” says lead author Carson Kautz, a graduate student in the Rochester Department of Psychology.

Kautz is working on interventions to reduce the adverse outcomes for children with developmental disabilities, particularly FASD, together with her faculty mentor and recognized FASD expert Christie Petrenko, an assistant professor and research associate at the University’s Mt. Hope Family Center. Petrenko is a co-author of the study, as is Jennifer Parr, a graduate student at the University’s Warner School of Education and a project coordinator and therapist at Mt. Hope Family Center.

“Of course, stress reduction is important for all parents,” acknowledges Parr, “but it’s especially critical in caregivers of children with special needs, given that we know of their already high stress levels.”

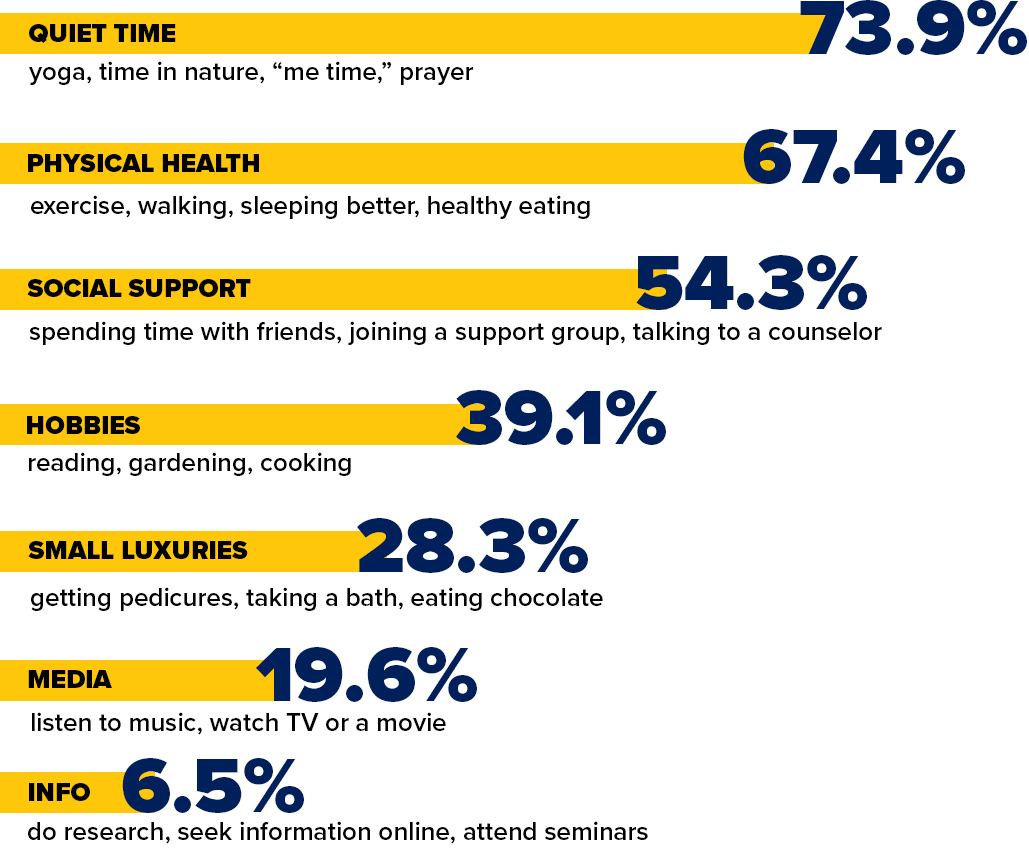

Most-used strategies for self-care

Source: University of Rochester researchers

This paper is the first to describe caregiver strategies for self-care and the obstacles and barriers parents face in raising their children while trying to care effectively for themselves. Based on interviews and questionnaires given to 46 caregivers of children with either an FASD diagnosis, or confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure, the researchers checked for child behavioral problems, parental stress levels, and grouped the various self-care strategies (such as practicing yoga, maintaining physical health, engaging in hobbies, and treating oneself to small luxuries) into seven categories.

“A strategy that really works well for one person may not work well for another, so it’s good to see people figuring out what works for them,” says Kautz.

Key findings

- Caregivers who report greater confidence in their ability to use self-care also report reduced parental distress, higher family needs being met, and greater parenting satisfaction.

- The frequency of self-care increases a caregiver’s confidence that self-care really helps.

- However, the frequency of self-care does not show a positive effect on any other measure of child or family functioning, such as child behavior, parent-child interactions, or perceived parenting effectiveness.

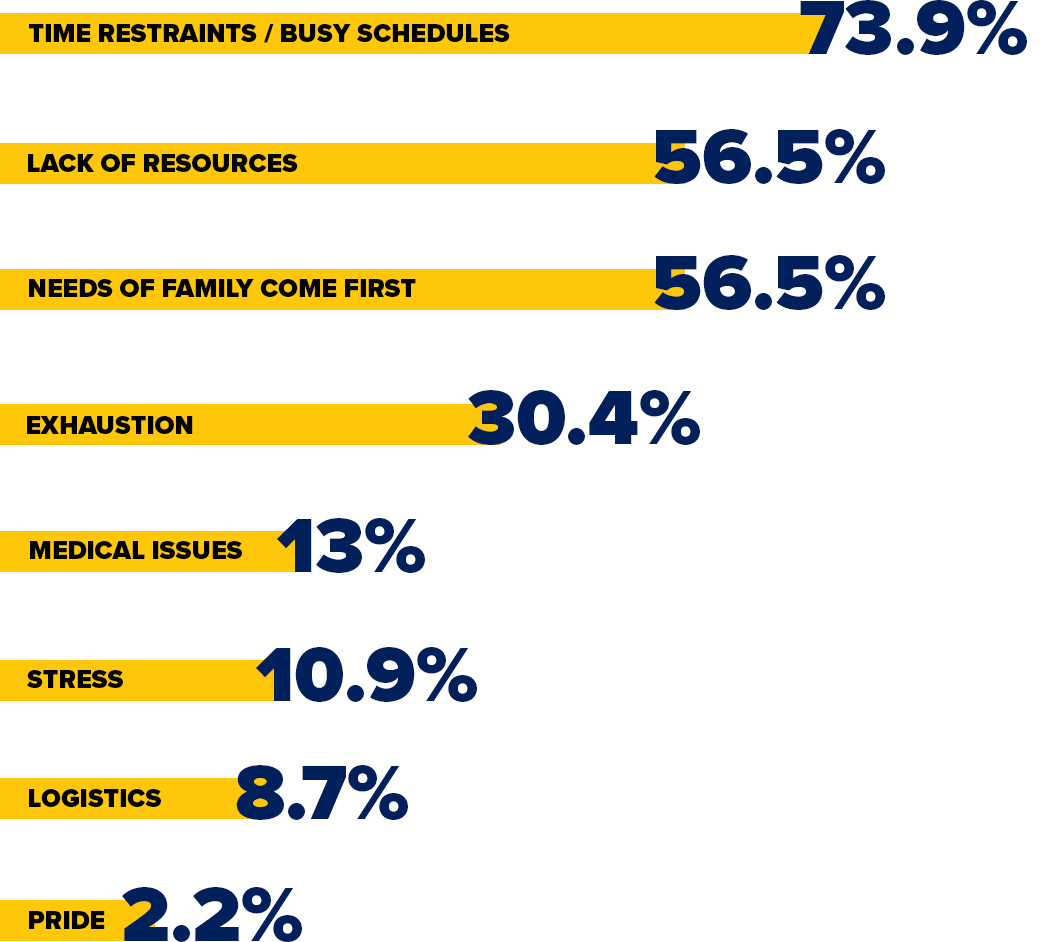

- Caregivers report a range of useful self-care strategies, but say they can be hard to fit into busy lives.

Most-frequently cited obstacles to engaging in self-care

Source: University of Rochester researchers

Previous research has shown that stress-reduction interventions, such as behavioral parent training, coping skills education, and particularly mindfulness exercises have shown promise in reducing the stress levels of parents of children with developmental disabilities.

The Rochester team hopes that the findings in this study, which was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, will inform future clinical work with parents of children with FASD.

Read more