Women of Invention is a Newscenter series of profiles of women at the University who hold international patents. More than half of the University’s patent applications from 2011 to 2015 include women.

Jannick Rolland took a big chance in 1984.

She had just received her diploma—the equivalent of a master’s degree—from the Institut D’Optique in Orsay, France. But she wasn’t sure whether she should pursue her aptitude for optics—or her talent for dance.

She wanted to come to the United States to become more fluent in English. But she was three points shy of passing an oral language exam to enter the University of Arizona.

She got on a plane anyway. She landed in Tucson, marched to the admissions office, and literally “talked her way” into the university.

Within months she was being encouraged to join the PhD program in optical engineering.

It was the turning point of her career.

A pioneer in freeform optics

Rolland is now the Brian J. Thompson Professor of Optical Engineering at the University of Rochester.

She directs the Center for Freeform Optics, a federally supported collaboration involving Rochester, the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and 18 companies and research institutes. The goal is to advance an emerging technology that uses lenses and mirrors with freeform surfaces to create optical devices that are lighter, more compact, and more effective than ever before.

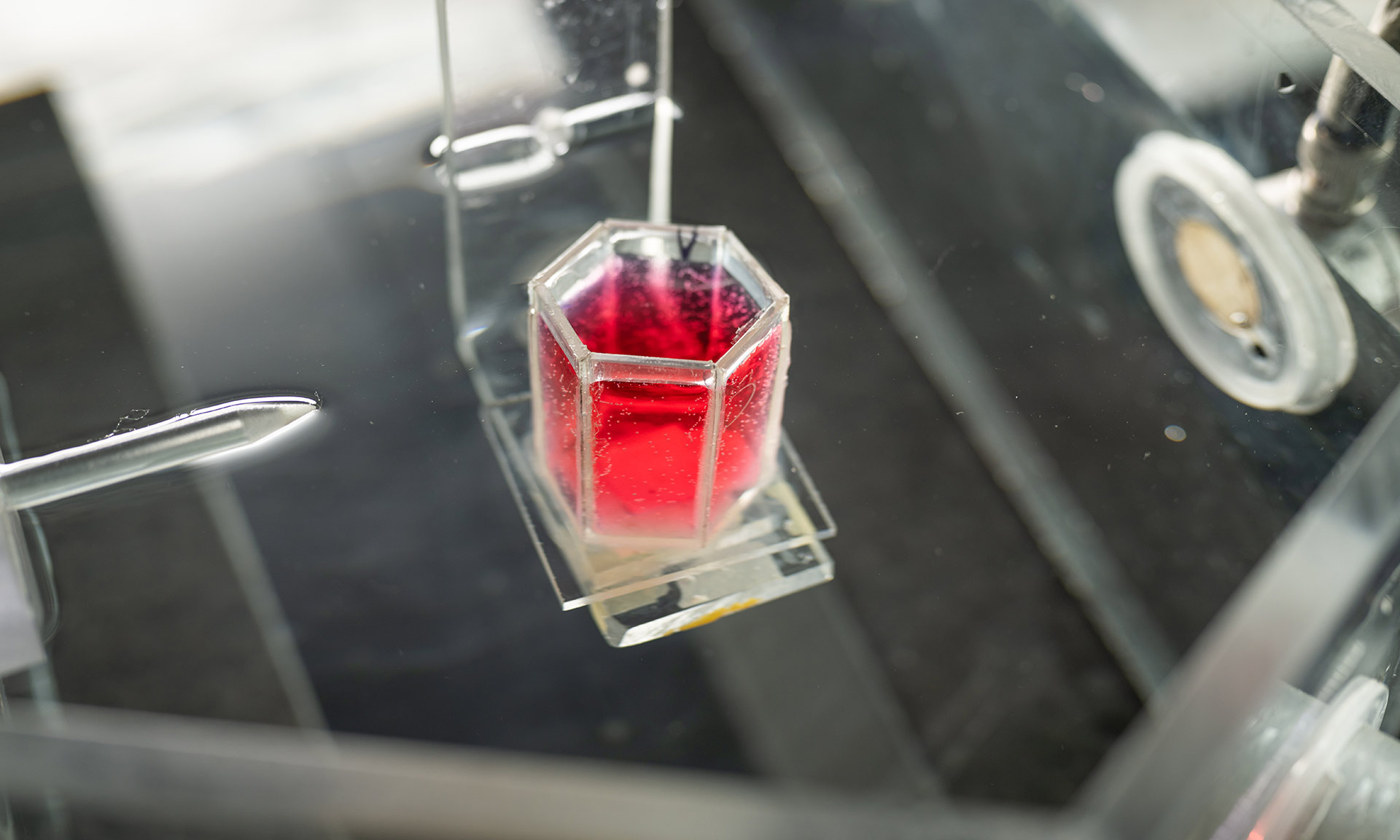

With her former PhD student Cristina Canavesi, she is also cofounder and chief technology officer of LightopTech, a startup commercializing one of Rolland’s inventions. The portable device uses a microscope with a liquid lens to image cells just below the surface of the skin, cornea, and other tissues. Among many possible applications, the device is targeted to help surgeons determine if they’ve successfully removed all of a skin cancer, without having to wait for the results of a traditional biopsy.

Rolland has 35 patents to her credit, and last year was listed among eight women pioneers in augmented and virtual reality by the organizers of the world’s largest AR/VR conference and expo.

Rolland may have had early doubts about pursuing optics as a career. But in retrospect, perhaps it is not surprising that she did.

When her mother took her at age 16 to a Parisian theater to see a production of Molière, it wasn’t the play that interested Rolland, but the special effects.

“During the whole play I was watching the back of the room, seeing how they used light and sound to create the play experience,” Rolland recalls.

At the end of the play she pointed at the back of the room and told her mom, “this is what I want to do.”

Optics or dance?

As a child, Rolland excelled in ballet, and eventually progressed to modern dance and jazz. Her parents were told she was talented enough to dance professionally.

Her father, despite a lack of formal education, was “naturally talented in physics.” So was his daughter, who showed an equal aptitude for math and computer science.

Rolland finished valedictorian of her class in a two-year physics program at the Institut Universitaire de Technologie in Orsay, and in the top 10 percent of her class at the Institut d’Optique.

But some of the instruction at the Institut d’Optique had been “a little too much ‘push button’ for me,” Rolland says. “We were not encouraged to ask questions outside the box, just solve the problem in the typical way, just get the results. I was hungry for more.”

Hence her doubts about optics as a career.

However, she experienced a far different approach at the University of Arizona’s Optical Sciences Center. “I was surrounded by researchers who were very excited about what they were doing, and really engaged in it,” Rolland says. “And the professors encouraged us to ask questions of all sorts. It took me awhile to adjust to this new kind of culture. But I really liked it.”

Her thesis was titled “Factors Influencing Lesion Detection in Medical Imaging.”

Postdoctoral and faculty postings followed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Central Florida’s College of Optics and Photonics (CREOL).

Working ‘at the boundaries’ of optics

During this time, Rolland was often working “at the boundaries” of her field, collaborating with computer scientists, for example, on the design of head-worn augmented and virtual reality devices. These relationships helped her develop new skills and unique areas of expertise.

But by “working at the boundaries,” she risked alienating colleagues in her own field, and even her chances of gaining tenure, Rolland says. So, she had to walk a careful tightrope.

After creating the technology for her liquid lens device at CREOL, she came to Rochester to join the faculty of the Institute of Optics in 2009.

The University’s Medical Center offered her a chance to collaborate with researchers on refining the biomedical applications of the device. And Rochester’s regional reputation as a center of optical manufacturing also attracted her.

“I felt the ecosystem would be better for what I am doing, and in fact, that’s what has happened,” Rolland says.

For the “first time in my life,” Rolland says, she finds herself surrounded by colleagues “who share common interests with me.”

Where before she worked alone, she now has collaborators who have been indispensable in helping her launch the Center for Freeform Optics.

“Communicating experiences people haven’t had before”

Rolland no longer takes to the dance floor. But she still likes to watch dancers.

“Dance is an amazing, nonverbal way of expressing yourself,” Rolland says. “It gives you a way to convey feelings and emotions that words cannot express.”

So do some of her current projects.

Her work in designing freeform optics for AR/VR glasses, for example, “is another way to communicate experiences that people haven’t had before, so there’s a commonality in all of this.”

In 1984, her professors inquired if she might be interested in pursuing a career in computer science.

“I might have gone into that as well,” Rolland says. “I was good at it. But at the time, all the news stories said there was no future in it.”

She chuckles about that now. And, no, she has no regrets about that career decision either.

Suffice it to say that her two grown sons are both computer scientists.

“And where do you think they got that?” Rolland says.