Editor’s note: As of 2024, the therapy discussed below remains experimental and is available only as part of a clinical trial. You can register via ClinicalTrials.gov or email christine_callan@urmc.rochester.edu to find out more about ongoing or upcoming trials.

Maybe you’ve recently suffered a stroke and are now starting therapy, trying to regain speech, motor functions, and possibly improve memory. But your vision is damaged, too, and there’s no therapy available.

Yet.

Krystel Huxlin, director of research and the James V. Aquavella Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Flaum Eye Institute, has been working in her lab over the last ten years to change that. Here’s how she sums up her latest results, published earlier this year in the journal Neurology:

“If people do exactly what we tell them and they don’t cheat, the success rate has been in our hands a 100 percent.”

Listen here to the full QuadCast interview with Professor Krystel Huxlin.

podcast transcript (.docx)

Huxlin spoke at the inaugural Light & Sound Interactive conference in Rochester, jointly sponsored by the University of Rochester and the Rochester Institute of Technology, as part of a panel on blindness and visual impairment that addressed corrective, restorative and rehabilitative approaches.

According to Huxlin, rigorous visual training can restore some of the basic vision lost in stroke patients with damage in the primary visual cortex. Damage to this area of the brain prevents visual information from getting to other brain regions that help make sense of it, causing loss of sight in one-quarter to one-half of the person’s normal field of vision.

“Traditionally it was thought that you cannot do anything about this. But one of the things we have discovered is that strokes rarely destroy the entire parts of the brain that process visual information,” Huxlin says. Her therapy involves training other, undamaged parts of the brain to take over—in a way, like starting a backup system.

The downside of pioneering a therapy is that Huxlin has a long waiting list of patients eager to be enrolled in her next vision restoration therapy study. So, if you are looking for a vision therapist today, your chances are slim.

“We feel like the lone voice in the wilderness,” she says. “It’s my hope that in the next few decades there will be more scientists who turn their attention to this problem and ways of resolving it.”

The good news is that her team is about to start a clinical trial for her therapy, funded in part by the University of Rochester, NYSTAR, the Data Science Institute, and Envision LLC. An FDA approval process for the treatment is to follow. Huxlin hopes the therapy can be rolled out to stroke victims across the United States within the next two years.

“We really have no time to waste,” she says. “There is a saying in the neurology community that time is brain. And I would say in this case—time is vision.”

The therapy is geared toward those whose visual system in the brain is damaged from traumatic brain injury, stroke, or a tumor. It’s not really designed to help those whose eyes are physically damaged, although Huxlin says it might also improve the ability to use vision in the latter group.

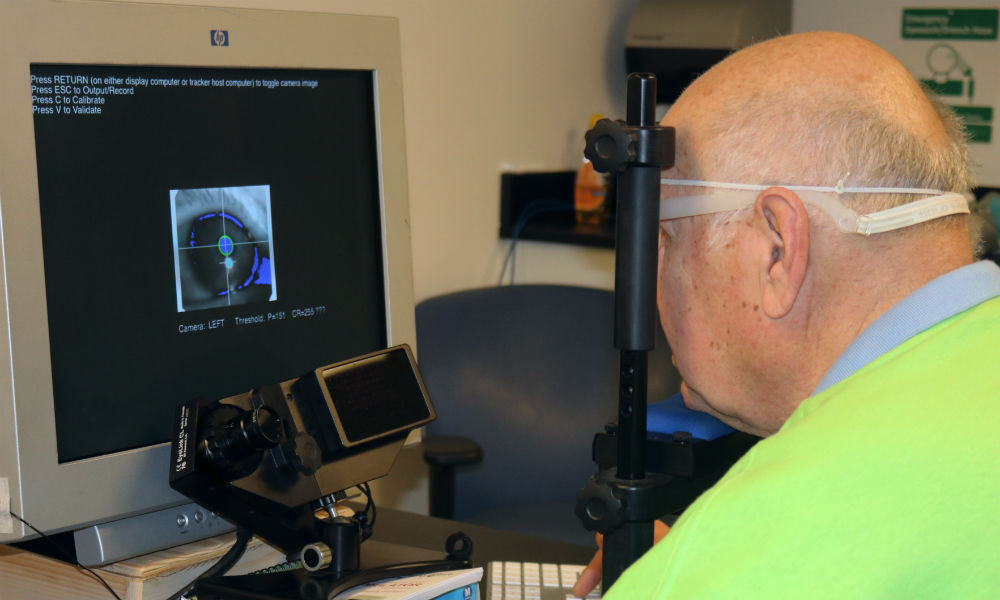

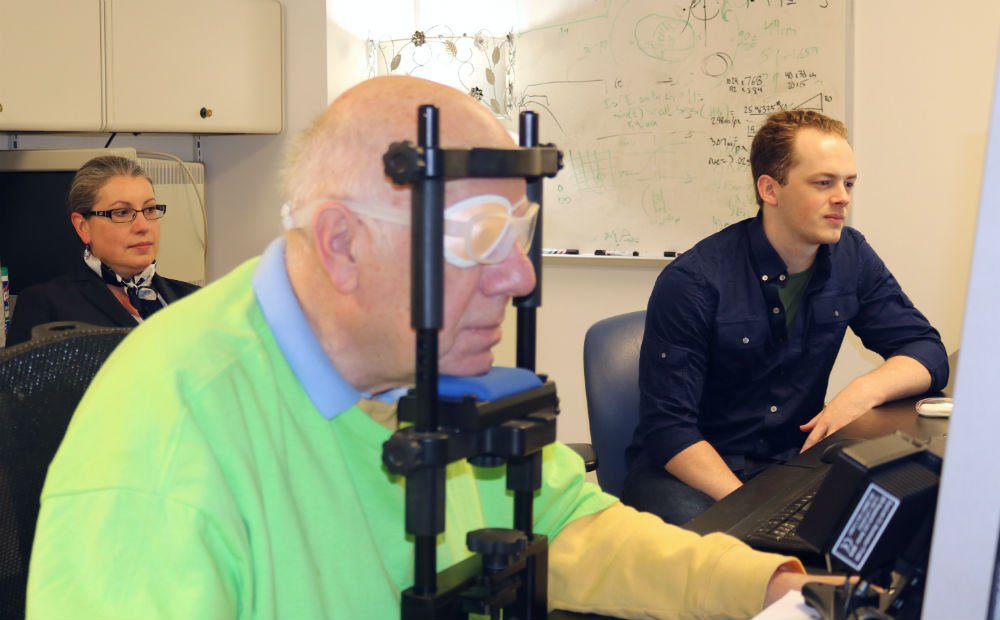

During the therapy, patients, steadied by a headrest, fix their eyes on a particular spot on a computer screen, in order to follow a visual stimulus that moves markers across the screen into the patients’ blind field. They try to locate and describe the marker’s attributes–whether it’s moving left or right, horizontally, or vertically—without moving their eyes and receive immediate feedback about their accuracy. Done for about an hour each day, for weeks, sometimes months, this approach trains patients’ brains to relearn to see correctly within those blind fields.

“We give them feedback and make them do it thousands of times,” explains Huxlin.

Now Huxlin is hoping to get the word out—to both patients and the medical community at large—that there’s real hope for restoring and relearning vision.

“Honestly, it should be administered just as automatically to patients with strokes as physical therapy is.”