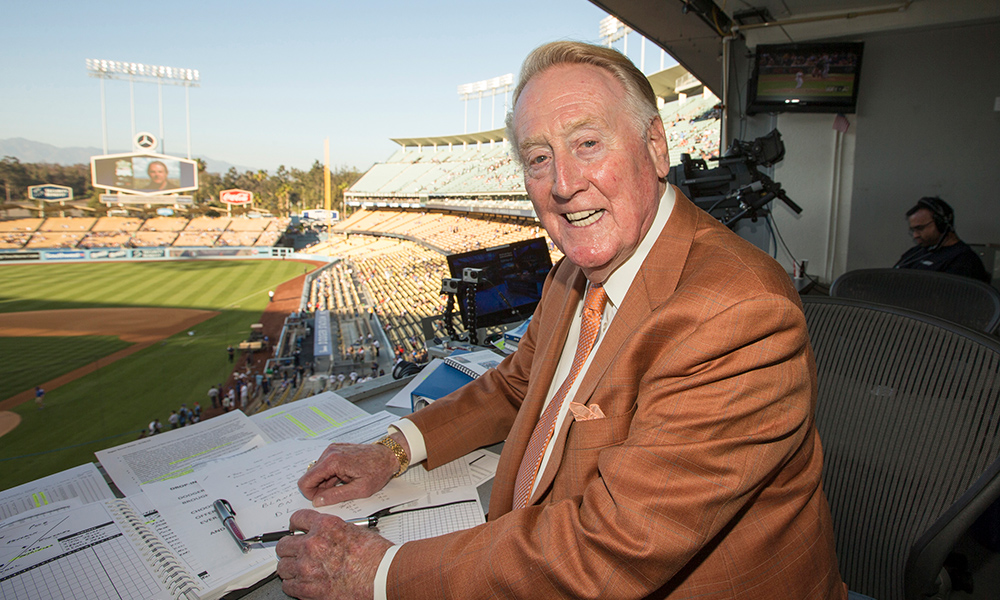

The author of multiple books on baseball, its storied stadiums and legendary broadcasters, recalls a baseball broadcasting legend.

Curt Smith is a senior lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Rochester. His 18 books include Voices of The Game and Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story. USA Today called him “the voice of authority on baseball broadcasting.” Smith was also a speech writer for President George H.W. Bush, with whom he worked for 14 years.

In 1945, journalist Edward R. Murrow said of World War II that Winston Churchill “had mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” From 1950 to 2016, Vin Scully mobilized that language to reach a new peak of radio and television brilliance, daily asking us to “Pull up a chair.”

Vin died on August 2 at 94, having announced the Brooklyn, then Los Angeles, Dodgers for 67 years—the longest such broadcasting streak. For a time, fans knew Vin from a network World Series here, an All-Star Game there. Later, we listened to Scully on 1970s CBS Radio, the 1983–89 NBC TV Game of the Week, then XM satellite radio. To paraphrase film’s The Natural, Scully was “the best there ever was.”

Born in 1927 in Manhattan, Vin at age eight discovered a magic place beneath an Emerson radio “that sat so high off the ground that I was able to crawl under it,” he told me in a 1986 conversation. Each Saturday, Vin put a pillow on its crosspiece and listened to college football broadcasts. “I shouldn’t have cared about a game like Florida-Tennessee,” said Scully, “but I did, getting goose bumps from the roar of the crowd.” He was hooked.

After high school, Scully joined the Navy, then entered Fordham University, where a classmate recalled him as “everywhere, recording himself.” At 21, he met famed Brooklyn baseball and CBS radio voice Red Barber, who hired him to call football and soon the Dodgers. In 1953, Barber left the team, and Scully replaced him—at age 23!—on World Series TV. Trying to “play it cool,” Scully ate breakfast with his parents the day of the Series opener. “Then I went upstairs and threw up.”

‘Ladies and gentlemen, the Brooklyn Dodgers are the champions of the world.’

In 1955, Scully called Brooklyn’s first World Series title after the team had lost six times to the Yankees: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Brooklyn Dodgers are the champions of the world.” All winter, people asked how he stayed so calm. “If I had to say another word, I think I would have cried,” Scully said.

In Brooklyn, the Dodgers televised each game. In late 1957, moving them to Los Angeles, owner Walter O’Malley banned TV broadcasts. Interest turned to radio, of which Scully was a wiz, the Fordham English major routinely coining phrases like “it was so hot today the moon got sunburned” and “he catches the ball gingerly, like a baby chick falling from the tree.”

—Vin Scully

While Dodger Stadium was being built, the club occupied huge Memorial Coliseum, with a capacity of more than 90,000. Thousands brought radios to a game, hearing Scully report what they couldn’t see. One day in 1960, Scully noted that it was umpire Frank Secory’s birthday. “I’ll count to three, and everybody yell ‘Happy birthday, Frank!’” Scully told his listeners. He counted, and the crowd yelled, “Happy birthday, Frank!” Secory almost fainted.

In the 1959 World Series, Scully and NBC reached a composite record 120 million of America’s then-150 million people. In 1965, Vin described Sandy Koufax’s perfect game—all 27 batters retired without reaching base—so flawlessly that a writer wrote, “It read like a short story” composed not with a pen but on the air.

Scully often likened play-by-play to starting each game with an empty canvas. “With radio, you come into the booth, bring your brushes and pallets, and you mix the paint and put things together,” he said. “And at the end of three hours, you say, ‘Well, that’s the best I can do today.’ On TV, the picture’s already there. So, what you’re doing is shading.”

In the ’70s Vin broadcast tennis, golf, and pro football for CBS. Increasingly, he also used silence as a dramatic tool. In 1974, calling Henry Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run in Atlanta, Scully hushed for nearly half-a-minute, then said, “A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol”—majesty to match the moment. It became a trademark of his, especially in his time at NBC.

Scully broadcast a nonpareil 25 Series; made every major radio/TV Hall of Fame; received an Emmy Lifetime Achievement Award, Commissioner’s Achievement Award, and Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame; and was named “most memorable [Los Angeles Dodgers] franchise personality” and in 2000, “Sportscaster of the Century” by the American Sportscasters Association, which voted him “Top Sportscaster of All Time” in 2009.

Scully brought eloquence, modesty, and literacy to each broadcast

Scully eventually cut his Dodgers slate, still daily saying, “Hi, again, everyone, and a very pleasant good afternoon to you wherever you may be. It’s time for Dodger baseball!” In 2016, he ended his last game by telling the audience, “I’ll miss our time together more than I can say,” the public feeling the same. Scully’s death a year after his wife Sandra’s in 2021 left 32 children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren—more than the combined starting lineup of three big-league clubs.

In the end, what made Scully, Scully? Other sports carry the announcer. The announcer carries baseball. A three-hour game may see the ball in play 10 minutes. The Voice must navigate a sea of dead air, persona his paddle. Scully tied eloquence, modesty, literacy, a voice less rock ‘n’ roll than easy listening, and extempore ability to haul a story from the shelf, likening statistics to a drunk “using a lamppost for support, not illumination.” Hearing Vin was even better than being at the game.

Read more

Curt Smith: Vin Scully ‘the best there ever was’

Curt Smith: Vin Scully ‘the best there ever was’

Smith’s 2009 book, Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story is the only biography written on the iconic broadcaster. “He’s a very humble man, and I think he feels his work speaks for itself,” Smith says. “Nobody says a bad word about him. Nobody.”

A national pastime must have a national presence

A national pastime must have a national presence

As the baseball season opens, the league is looking to change some rules to speed up the game. English lecturer and baseball authority Curt Smith presents his own five-point plan to save the sport he loves.

The story of baseball in the United States is intertwined with that of the presidency, says senior English lecturer Curt Smith. He traces the points of connection from the colonial era to the present.

Pitching politics

Pitching politics