University of Rochester researchers have developed SOPHIE, a virtual ‘patient’ that trains doctors in explaining end-of-life options.

As many as 68 percent of late-stage cancer patients leave their doctor’s offices either underestimating the severity of their disease, overestimating their life expectancy—or both. These misunderstandings can hinder the ability of patients and their families to make realistic decisions about whether to continue aggressive treatments or instead turn to palliative care.

To address the problem, University of Rochester computer scientists, palliative care specialists, and practicing oncologists are perfecting SOPHIE (Standardized Online Patient for Healthcare Interaction Education)—an online virtual “patient” that helps physicians practice how to communicate effectively with late-stage cancer patients about their disease.

Effective communication in this context often means demonstrating empathy and understanding of the complex emotions that patients are experiencing.

“During difficult conversations about facing the potential of one’s own death, patients are frightened and don’t know how to ask the right questions, and clinicians may oversimplify, omit, or sugar-coat information, or feel too pressed for time to address patients’ emotions,” says Ehsan Hoque, an associate professor of computer science at Rochester’s Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. The COVID-19 pandemic has made effective communication even more difficult by causing increasing reliance on virtual rather than in-person interactions between patients and physicians, adds Hoque.

Hoque is a pioneer in the area of research that shows it is possible for people to learn and improve their social and interpersonal skills by interacting with automated systems. For example, he helped develop LISSA (Live Interactive Social Skills Assistant)—a tool that’s been used effectively by people on the autism spectrum—in collaboration with professor of computer science Len Schubert.

Practicing end-of-life conversations

SOPHIE is possible because of a body of nearly 400 conversations that were recorded between late-stage cancer patients and their oncologists, and initially analyzed by palliative care expert Ronald Epstein and his collaborators at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Epstein’s Center for Communication and Disparities Research focuses on how to improve communication between clinicians, patients, and their loved ones.

A paper in IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing describes how lead author Mohammad Rafayet Ali, a postdoctoral researcher, and PhD student Taylan Sen, both members of Hoque’s Rochester Human-Computer Interaction (ROC HCI) Lab, created algorithms that could be applied to the transcripts of these conversations, so the researchers could develop metrics to assess a physician’s ability to communicate clearly with patients.

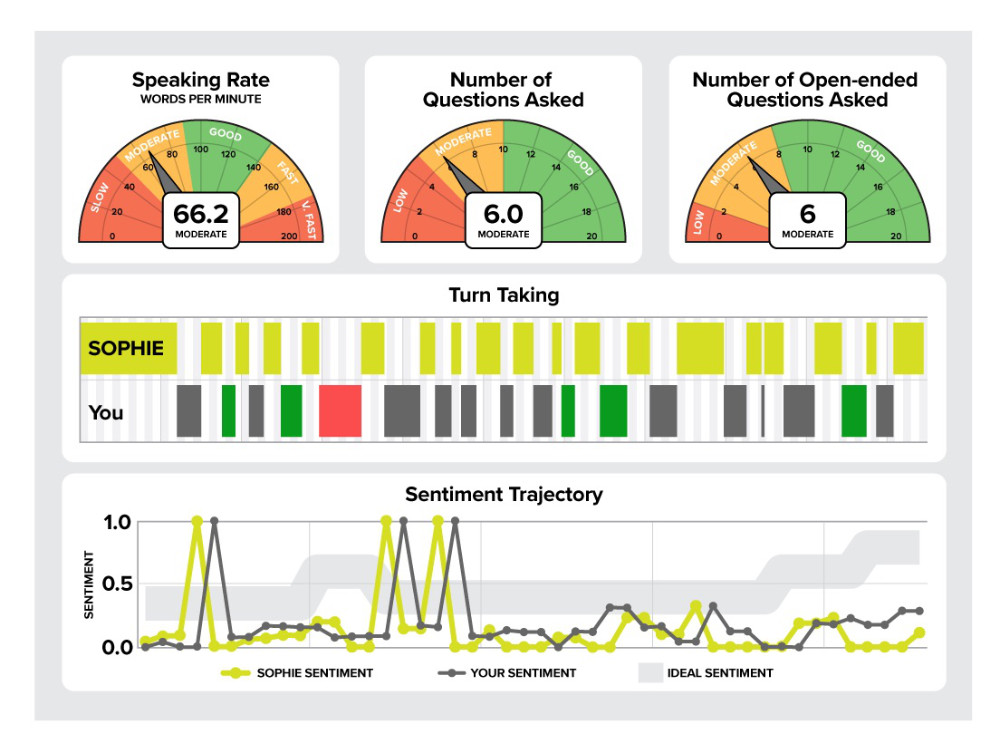

The metrics focus specifically on the extent that physicians engage in lecturing—delivering a lot of information without giving the patient a chance to ask questions or to respond—or, on the plus side, how well they employ “sentiment trajectory”—using positive words and phrases in ways associated with increased patient understanding.

The researchers used a physician communication training protocol, developed by Epstein and his collaborators, to script SOPHIE’s practice sessions, and enlisted nine practicing oncologists at the University to try the system.

“We received a lot of feedback from the doctors on how natural the conversation was, the kinds of questions SOPHIE should ask, and the concerns a typical patient might raise,” Ali says.

“In our prior research, physicians practiced with trained actors to learn how to bring up difficult issues, such as prognosis and end-of-life care,” Epstein says. “But actors can be costly. The online format can provide training at a fraction of the cost and be made available to physicians worldwide. And Ehsan Hoque’s group is on the cutting edge.”

The researchers are now fine-tuning SOPHIE. “Our hope is that once we have demonstrated its efficacy through a randomized controlled experiment, first-year students at the Medical Center can practice with it,” Hoque says.

The demo has been designed to be available through a computer browser, allowing physicians from anywhere around the world to practice their skills live and receive feedback on their speaking rate, turn-taking, type of questions asked and sentiment trajectory.

SOPHIE could help raise awareness of palliative care as an option. “In many parts of the world, there is no palliative care. People only focus on how to treat the cancer,” Ali says.

SOPHIE says

A sample conversation with SOPHIE works something like this:

SOPHIE appears as a real-life—albeit, AI-derived—human face on the user’s screen.

She introduces herself and mentions that she has lung cancer. Then SOPHIE raises the topic of her sleep pattern at night and asks if she needs to change her pain medication, allowing the physician to assess her perception. She states that her current pain medication, Lortab, is not working anymore.

As the doctor responds, SOPHIE begins collecting data so that she can provide the doctor with an end-of-conversation assessment resembling the image above.

SOPHIE then turns attention to her test results, giving the physician a chance to engage SOPHIE in more difficult topics, before asking more specifically about her prognosis.

SOPHIE next asks about other options and expresses some additional fears and concerns, providing the physician with opportunities to respond empathically.

Finally, she follows up by discussing whether chemotherapy remains an option, whether she should focus on comfort care, what the side effects of chemotherapy are, and how to break the news to her family, allowing the physician to summarize information and suggest a strategy.

Close proximity fosters collaboration

The SOPHIE project is a shining example of the research collaborations that are possible as a result of the close proximity of the University of Rochester Medical Center to the rest of the University. The River Campus, for example, is just a five-minute walk away.

The project had its origins seven years ago when Hoque, who had just joined the University, spoke to a digital media studies class on the River Campus. “An undergraduate student in the class was employed by Ron Epstein’s lab,” Hoque says. “She talked to Ron and suggested we should talk. We hit it off right away.”

Hoque and his lab members were impressed by Epstein’s work on improving communication between terminally ill patients and their physicians. They were especially excited by the research possibilities presented by the patient-physician transcripts that Epstein and his collaborators had begun analyzing.

“They did all the hard work in collecting high-stakes conversations of cancer patients,” Hoque says. “We were fortunate to be at the right place at the right time to leverage the data and their expertise.

“This wasn’t part of Rafayet’s and Tay’s thesis trajectories at all, and we didn’t have any funding to do the work. But we knew that we needed to find a way to do this exciting work.”

Other collaborators coauthors of the paper include Thomas Carroll, associate professor of medicine; Lenhart Schubert, professor of computer science; Benjamin Kane (advised by Schubert); and Shagun Bose, an undergraduate researcher in the Hoque Lab.

Read more

Ehsan Hoque named an ‘emerging leader’ by National Academy of Medicine

Ehsan Hoque named an ‘emerging leader’ by National Academy of MedicineThe director of Rochester’s Human-Computer Interaction Lab is one of ten leaders selected to work with the organization on “sparking transformative change to improve health care for all.”

Virtual reality app offers personalized psychotherapy

Virtual reality app offers personalized psychotherapyA multidisciplinary team of University doctors, engineers, and musicians worked together to create an immersive, customized experience that brings cognitive-behavioral therapy to a patient’s smartphone.

Machine learning advances human-computer interaction

Machine learning advances human-computer interactionResearchers at Rochester are developing computer programs incorporating machine learning to teach robots and software to understand natural language and body language, make predictions from social media, and model human cognition.