Walt Whitman poems figure prominently in American literature. In 2017, Ed Folsom ’76 (PhD) looked back on the legacy of the poet’s work.

March 26 is the anniversary of the death of Walt Whitman, one of the most influential voices in American—and world—literature.

Ed Folsom ’76 (PhD), the Roy J. Carver Professor of English at the University of Iowa, has devoted his professional life to understanding Whitman’s work. He’s the author of 10 books, including Song of Myself: With a Complete Commentary (University of Iowa Press, 2016), coedited with Christopher Merrill. He also coedits the Walt Whitman Archive, a resource for scholars and students around the world.

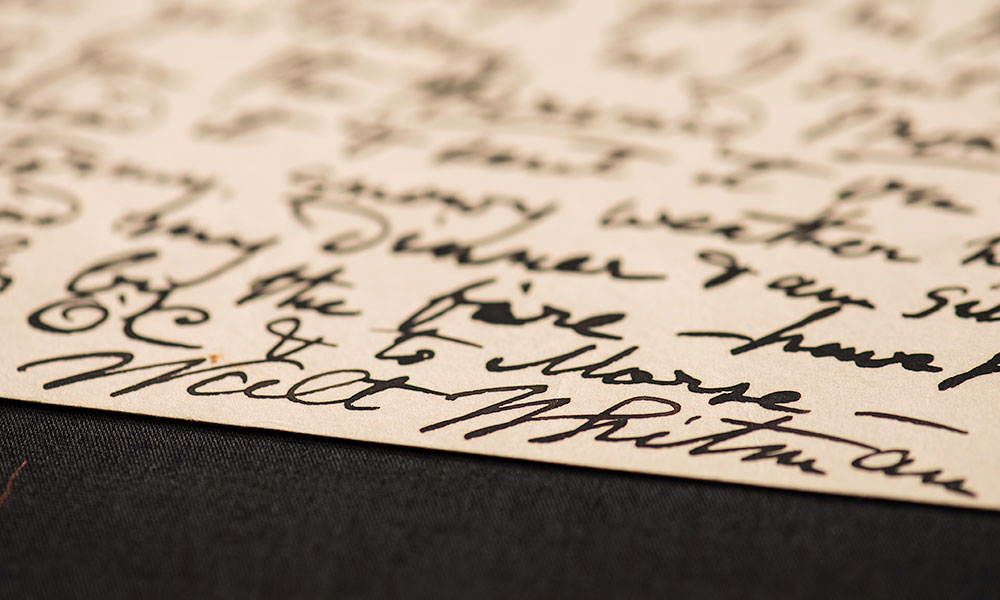

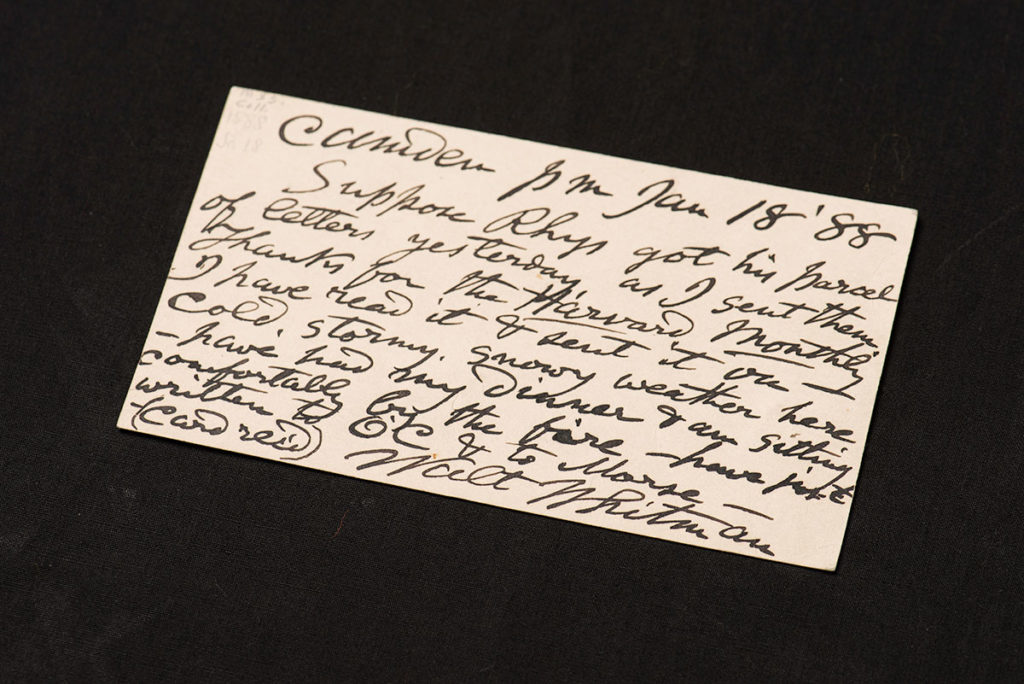

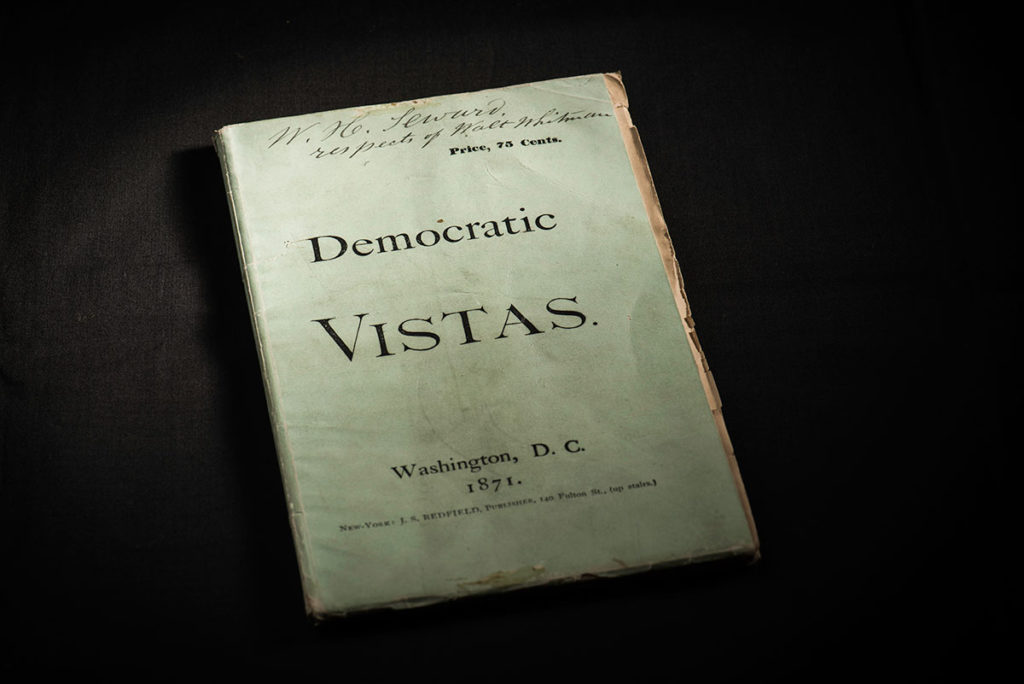

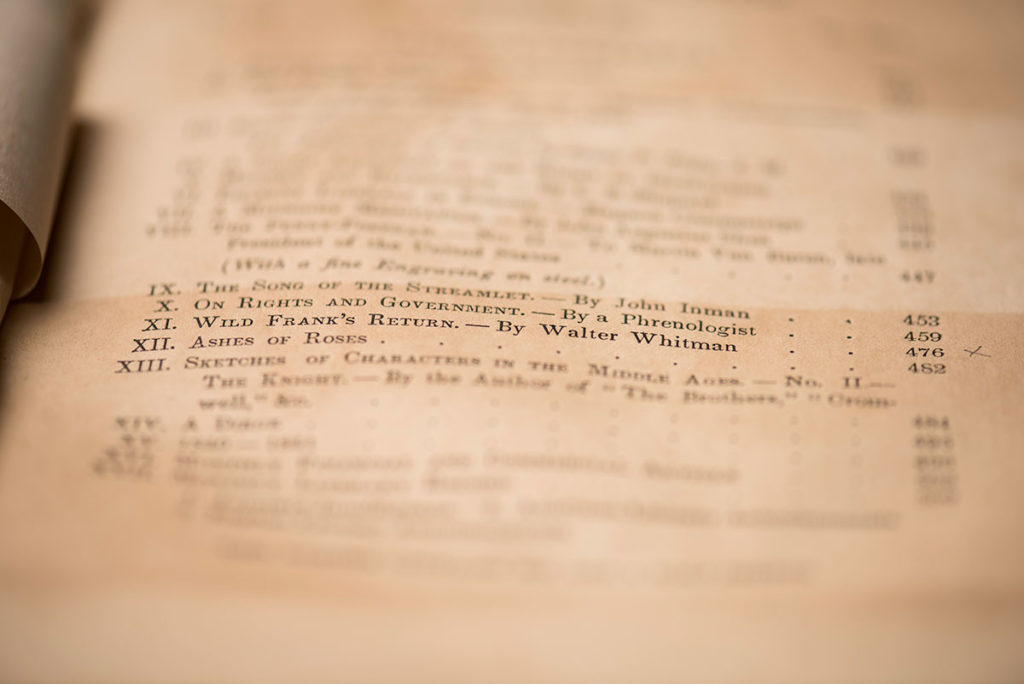

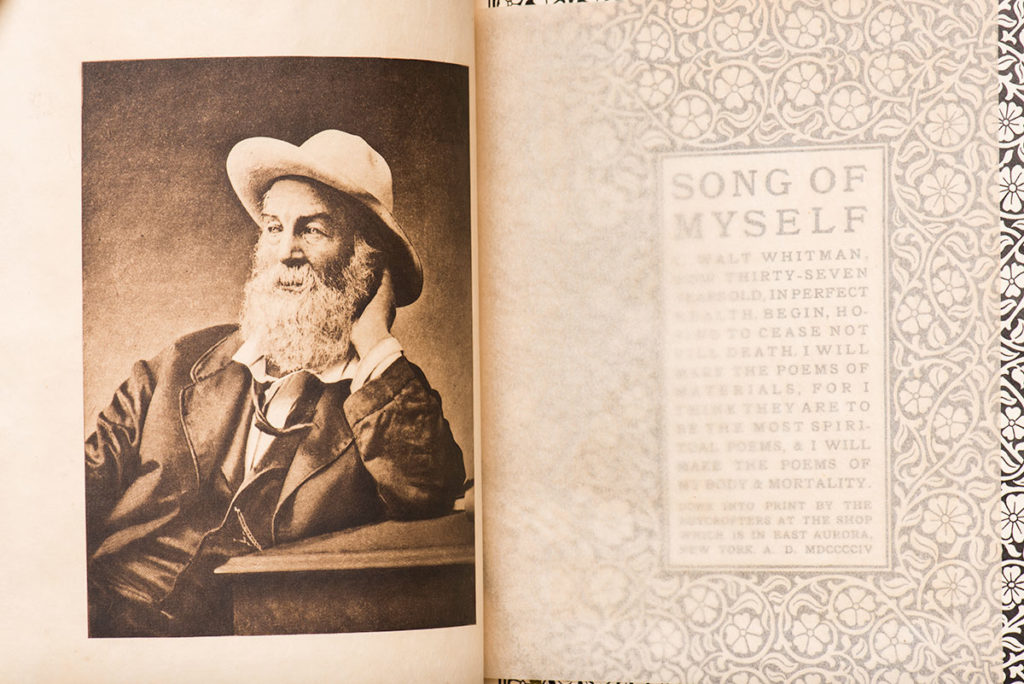

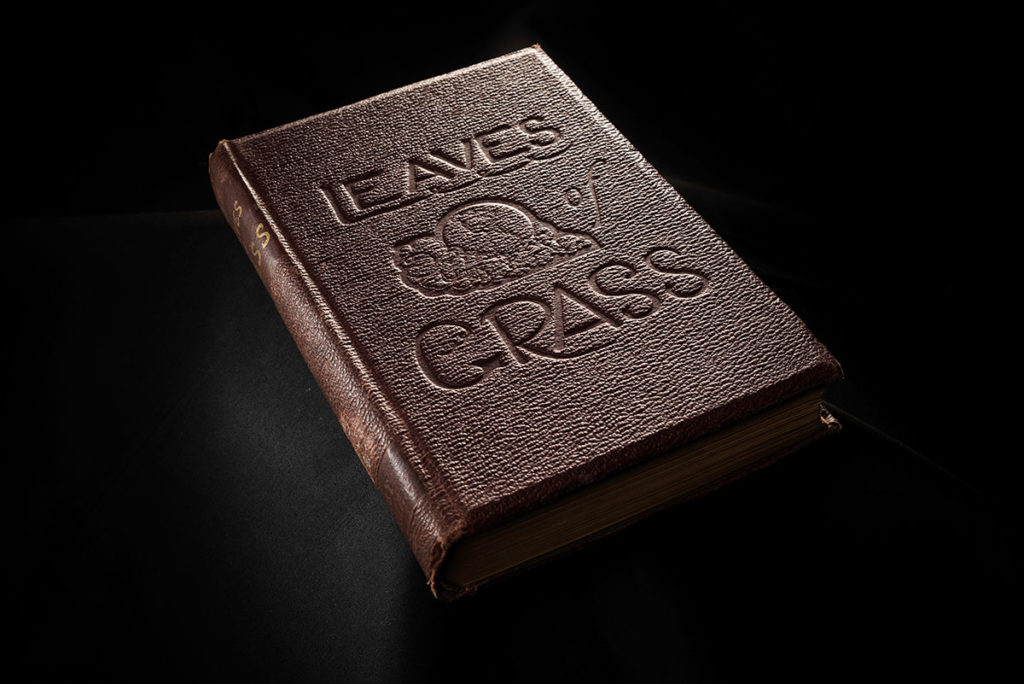

Walt Whitman poems, letters, and early editions are also available in the University of Rochester’s libraries.

(University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation / J. Adam Fenster)

What is Walt Whitman’s most enduring legacy?

Folsom: His impact on American literature over the past century and a half is incalculable. Virtually every American poet has at some point engaged Walt Whitman directly, often in a poem, as Hart Crane did in “The Bridge” or Allen Ginsberg in “A Supermarket in California.”

Whitman always addressed his poems to readers in the future, and American poets have talked back to him continually—arguing with him, praising him, questioning him about the diverse and democratic American future he promised. The list of American poets who have carried on this non-stop debate with him is endless: from Langston Hughes and Muriel Rukeyser to William Carlos Willams and Robert Creeley, from June Jordan to Yusef Komunyakaa to Marín Espada. American poets have viewed Whitman’s radical poetics as essentially intertwined with the national character, a kind of distinct and distinctive American voice.

This Whitmanian voice is heard throughout the broader culture as well—in films including Now, Voyager; Dead Poets Society; Sophie’s Choice; Bull Durham; The Notebook; Down by Law, and many more; in television series such as Breaking Bad, where Walter White’s name indicates the Walt Whitman connection, and where Whitman’s work plays a recurring central role; and in many recent ads, including those for iPad, Levi’s, and, most recently, Audi. Whitman has been set to music by over 500 composers, including Charles Ives and Ned Rorem, and his presence is felt in art installations everywhere, including Jenny Holzer’s recent New York City Aids Memorial, which features excerpts from “Song of Myself.”

What about his influence globally?

Folsom: Another poetic dialogue has been taking place outside of the country’s borders for the past 150 years, one that involves talking back to Whitman by an international group of writers—from Federico García Lorca to Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda, from Cesare Pavese to Czeslaw Milosz, from Fernando Pessoa to Artur Lundkvist, from Hermann Hesse to Thomas Mann, from Amin Rihani to Adonis, from Guo Moruo to Ai Qing, from D.H. Lawrence to Charles Tomlinson—as his influence has extended far and wide, not only across race and social class and ethnicity and poetic style, but across nationalities, languages, and continents. As the writer Michael Cunningham—whose book of novellas called Specimen Days focuses on Whitman—has noted, Whitman is now more like a public utility than a writer. His works and influence are so pervasive that artists in any medium view him as a source of power and sustenance that can be tapped into endlessly.

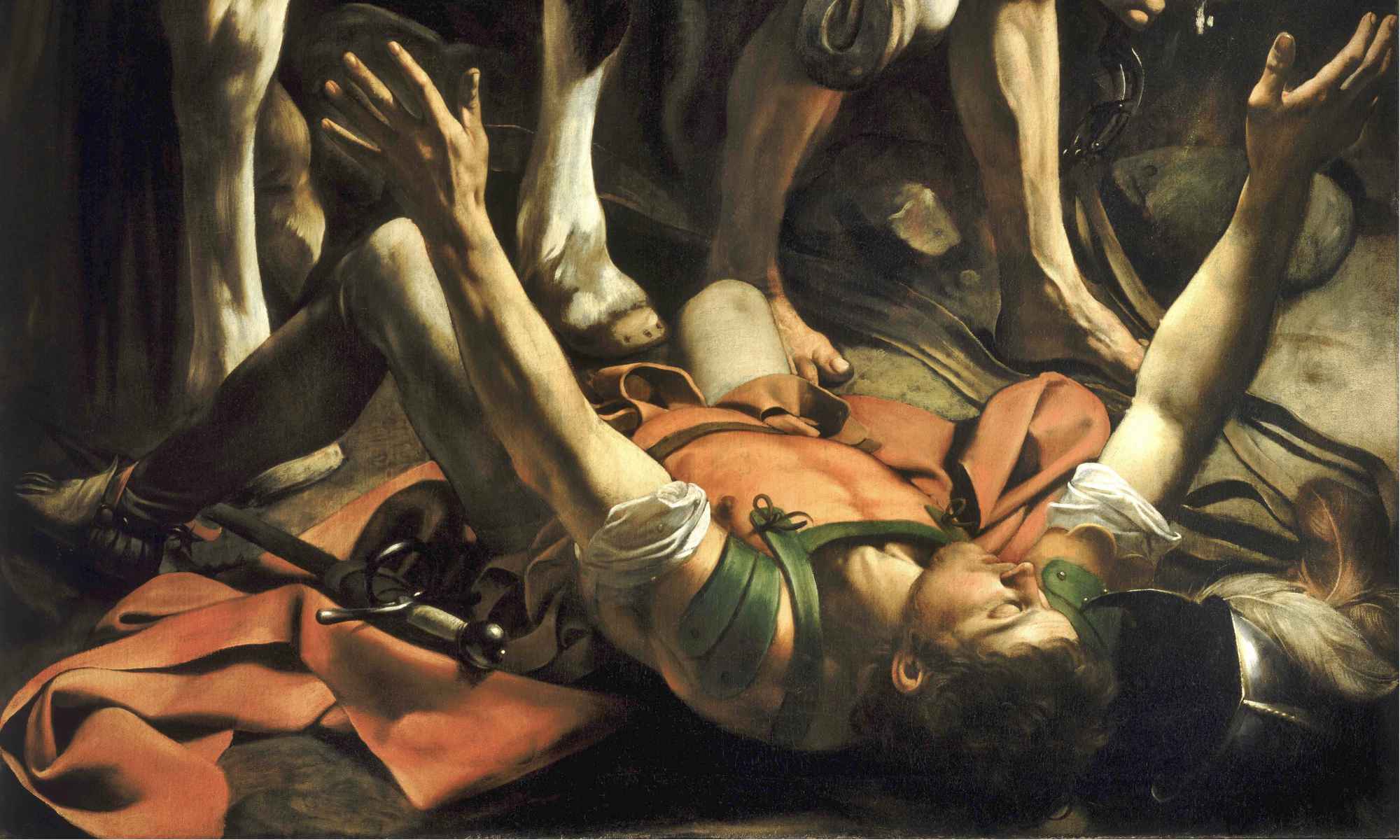

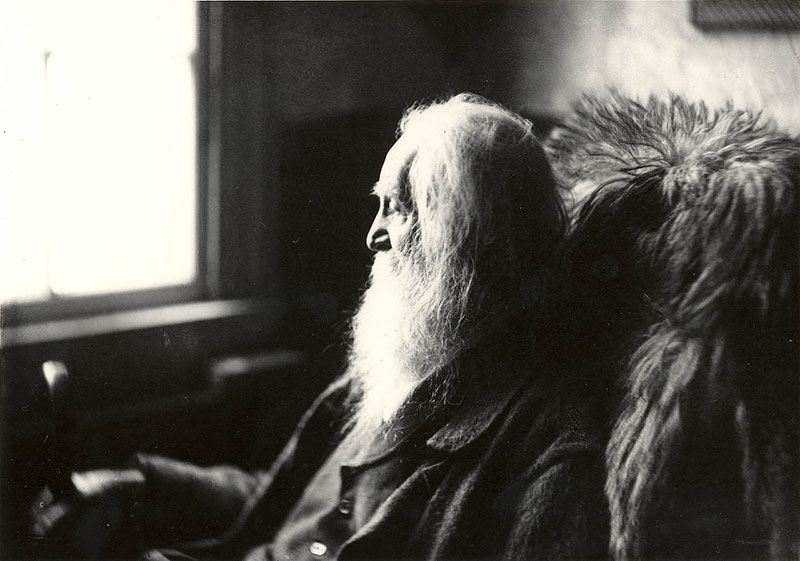

(University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation / J. Adam Fenster)

How did Walt Whitman become a poet?

Folsom: Whitman was an autodidact; he was done with his formal schooling by the time he was 12, and he learned by reading books he took out of lending libraries and by visiting museums and by walking the streets of New York and Brooklyn. He learned typesetting as a teenager and published his first newspaper articles in his mid-teens.

As he grew into the newspaper business, he developed a style of directly addressing his readers, something he would carry over with him to his radical new kind of poetry. That poetry drew from his journalism and from hearing orators speaking around the city. Whitman dreamed of becoming an orator himself and made notes for many speeches about America and democracy. He reshaped his journalistic voice and oratorical voice into a new kind of poetry that has traits of both journalism—an attentiveness to detail, an obsession with close observation of the world around him—and oratory—long lines that often have the cadence of a speech. It’s as if we’re hearing a spoken voice on the page, directly addressing the “you”—that slippery English pronoun that can mean a single intimate reader or a world of strangers.

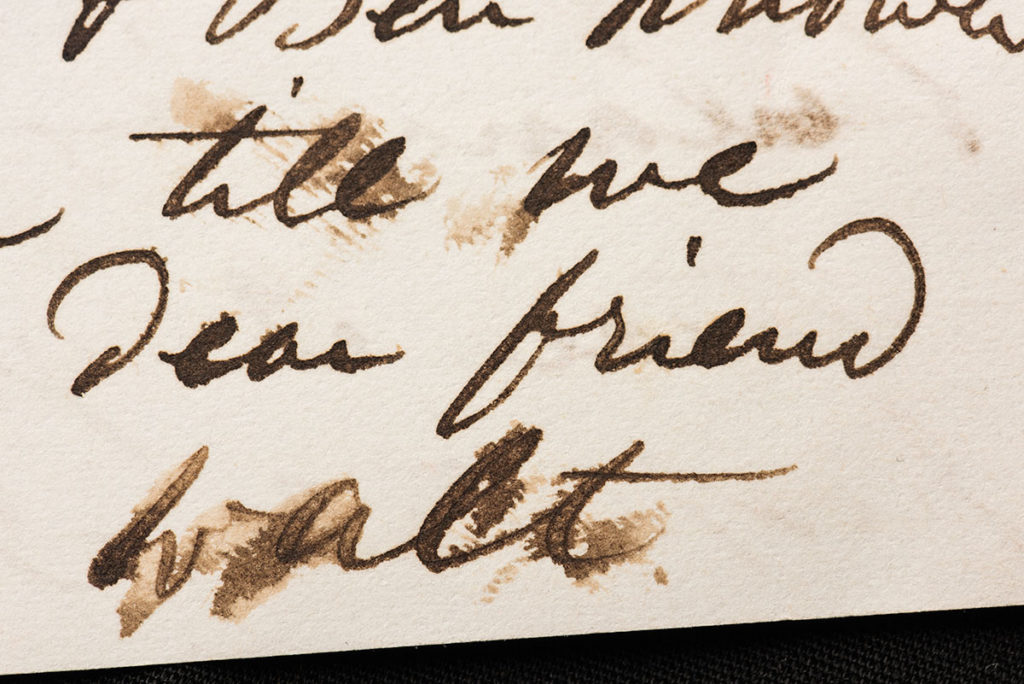

(University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation / J. Adam Fenster)

Where do you suggest someone begin when reading Walt Whitman?

Folsom: His poetry is about a celebration of the single, separate individual and, at the same time, the celebration of the “en-masse,” the wild diversity of a nation that manages to stay unified while “containing multitudes.” Nowhere is this fluctuation between self and cosmos, individual and nation, better seen than in his longest and best poem, “Song of Myself,” a work that every American owes it to herself or himself to read.

The new book I wrote with Chris Merrill is an attempt to help readers do just that: Chris and I talk about each of the 52 sections of the poem, so that readers can read the poem, then read our comments and begin joining in the give-and-take with Whitman that is the whole purpose of his work. Whitman demands that the reader actively talk back to the poetry and not accept it passively, and Chris’s and my commentaries set out to initiate that dialogue.

(University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation / J. Adam Fenster)

What do you make of Walt Whitman’s newly discovered novel, Life and Adventures of Jack Engle?

Folsom: The discovery of Jack Engle is extremely important because, for the first time, we have fiction written and published by Whitman after he had started writing the poems that would be included in his first edition of Leaves of Grass. Before this discovery, the latest known fiction by Whitman was published in 1848, and that always made it easy to assume that Whitman gave up fiction and took up poetry, since we had a convenient seven-year break between the last known fiction and the radical new poetry. Jack Engle was published in 1852, Leaves of Grass in 1855. Whitman had begun publishing his new free-form radical poetry in newspapers in 1850, so we now know that the poetry and fiction were mingling in ways we had never before known.

This makes us rethink everything we thought we knew about Whitman’s early writing career. Scholars and critics will be working on the implications of this for many years to come. We can now see that Whitman in the early 1850s was still unsure about what form his life’s work would take.

(University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation / J. Adam Fenster)

Is there any relationship between the novel and Leaves of Grass?

Folsom: The place in Jack Engle where we can see the themes of Leaves of Grass emerging is chapter 19, where the plot of the novel comes to a dead stop as Jack wanders through the cemetery at Trinity Church in Manhattan and contemplates the various grave plots around him. He begins to think about how all “plots” end in these grave plots, where inscriptions on gravestones give us only the bare outlines of a life.

Jack begins listening to the ongoing sea of life just outside the cemetery walls, and he realizes that life always flows past the places of death—it may be a different throng of people wandering past, but that flow of life is ever-changing and always ongoing. It’s here, at this moment, that we can feel Whitman losing interest in fictional plots—those things that begin, follow a trajectory, and have an ending—and beginning to become entranced with how to celebrate and focus on that ever-changing flow of life—that thing that has no beginning and no end and that transfers endlessly among shifting forms of matter.

The nature of democracy is under discussion around the world right now—and it’s a subject with which Whitman himself was deeply concerned. What could people learn from reading his work?

Folsom: When Walt Whitman first began making notes toward the poem that would become “Song of Myself,” he jotted down “I am the poet of slaves and the masters of slaves.” He was trying to assume a voice, in other words, that was capacious enough to speak for the entire range of people in the nation—from the most powerless to the most powerful, from those with no possessions to those who possessed others. If he could imagine such a unifying voice, he believed, he could help Americans begin to speak the language of democracy, because if slaves could begin to see that they contained within themselves the potential to be slavemasters, just as slavemasters contained within themselves the potential to be slaves, then slavery would cease to exist, because people of the nation would begin to understand that everyone is potentially everyone else, that the key to American identity is a vast empathy with all the “others” in the culture.

In “Song of Myself,” Whitman says “I am large, / I contain multitudes,” and this voice that is vast enough and indiscriminate enough to find within itself all the possibilities of American identity would become the great democratic voice, a voice for the citizens of the country to aspire to. Today, the nation is so divided in political and social and economic and racial ways that it has become impossible to imagine a single unifying voice that speaks for America. Every voice that claims to speak for the “American people” today is in fact a divisive voice, alienating as many Americans as it unifies. So Whitman seems more important now than ever.

It’s hard work to make the imaginative leap to a fully democratic voice, one that celebrates diversity and finds strength and unity in the wild variety that defines this nation. Whitman knew it would be difficult, perhaps impossible. During his lifetime, Whitman experienced a massive civil war, an entire generation of American men destroyed, when the union could not contain its multitudes and came apart at the seams. I think he would sense a similar danger today.

Editor’s note: This story was originally published on March 23, 2017. It has been republished to mark the 130th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s death.