This never-before-seen style of collective motion isn’t the only finding that surprised Rochester researchers about the organisms.

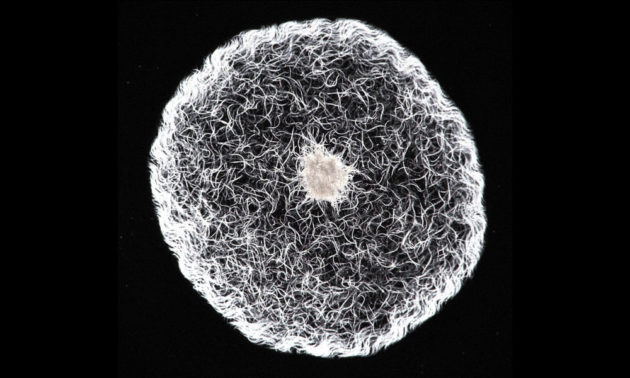

What happens when thousands of tiny vinegar eels are placed in a bead of water? According to researchers at the University of Rochester, they do the wave.

Anton Peshkov, a postdoctoral research associate in the lab of Stephen Teitel, professor of physics; Alice Quillen, a professor of physics and astronomy; and undergraduate student Sonia McGaffigan ’23 placed thousands of Turbatrix aceti, a species of millimeter-long nematodes (roundworms) commonly known as vinegar eels, in a drop of water. The small eels then exhibited several surprising behaviors, including coordinating their motions as they swarmed together. The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Soft Matter, liken the movement to a crowd doing the wave at a sporting event.

“This wavelike collective motion has not been seen before in any other organisms this large,” Quillen says.

Peshkov and Quillen have previously worked on models of active matter and granular systems, which are systems composed of many particles visible to the naked eye. They originally focused their research on briny shrimp—also known as sea monkeys—and how they move, but then decided to explore collective motion in a different type of organism.

A video recorded by the researchers shows that the vinegar eels swim randomly in the water droplet for a few minutes before some begin clustering in the middle while others move to the outer edge. Eventually, the individual eels at the border begin oscillating together and the swarm moves in an undulating, wave-like motion. The movement is a combination of swarming and synchronization.

Researchers have studied organisms that can move collectively, such as schools of fish or flocks of birds, or organisms capable of synchronization, such as flashing fireflies. But the nematode vinegar eels that Peshkov and Quillen studied are the first known species to combine both collective motion and synchronized oscillation in a single organism.

The special movement isn’t the only surprising thing the researchers found.

Once the vinegar eels began swimming in unison, the eels stirred up flows that pushed against the edge of the water droplet, preventing the droplet from contracting. This changed the physics of the water droplet’s evaporation by counteracting the surface-tension force. The researchers were able to measure the force exerted by the swarm of nematodes and found that each vinegar eel generated 1 micronewton of force. In other words, the tiny eels are capable of moving objects hundreds of times their own weight.

“These eels can produce new states of matter that were not explored before, like the collective moving metachronal wave that we present in our article,” Peshkov says. “By harnessing the strong fluid flows and propulsive forces that are produced, we could envision, in the future, displacing small objects inside fluids and creating on-demand fluid flows in microchannels.”

Read more

New data about asteroid surfaces will help explorers touch down safely

New data about asteroid surfaces will help explorers touch down safelyUsing sand, marbles, and mathematical modeling, Rochester physicist Alice Quillen studies what happens when objects touch down on complex, granular surfaces in low-gravity environments.

What sound does ice make when it’s dropped 90 meters into an Antarctic glacier?

What sound does ice make when it’s dropped 90 meters into an Antarctic glacier? Researchers in the University of Rochester’s Ice Core Lab shared a viral video that shows the “unexpected and fascinating” noise that ice makes when it hits the bottom of a borehole in Antarctica.

Firefly researchers mapping ‘world’s second-most interesting genome’

Firefly researchers mapping ‘world’s second-most interesting genome’Rochester biology Amanda Larracuente is a specialist in evolutionary genetics and genomics and has been involved in a project studying Photinus pyralis—or, the Big Dipper firefly.