Rochester economist Narayana Kocherlakota says a return to 1970s levels of inflation is unlikely—but offers a cautionary note.

A sizeable proportion of Americans today are old enough to remember the Great Inflation of the 1970s. Prices for everyday items soared, and at an increasing rate—peaking at 15 percent in early 1980.

So when the inflation rate, which has remained under 3 percent for a decade, nearly doubled from March to May of this year and continued to climb in June, it seemed reasonable to ask: will rising prices spin out of control again?

University of Rochester economics professor Narayana Kocherlakota, a former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, says that’s unlikely.

“The increase in inflation is a short-term blip,” says Kocherlakota, the Lionel W. McKenzie Professor of Economics. He attributes the blip to pent-up demand and a rise in hiring following the yearlong COVID-19 slowdown in production. He adds, “It’s a small price to pay for the fact that we’re providing more employment to so many more people.”

What is inflation?

Inflation refers to the rate of change in the prices of goods and services. But different goods’ prices change at different rates. That means the inflation rate depends on how one averages the prices of all of the goods and services in the economy. There are several different measures in common use.

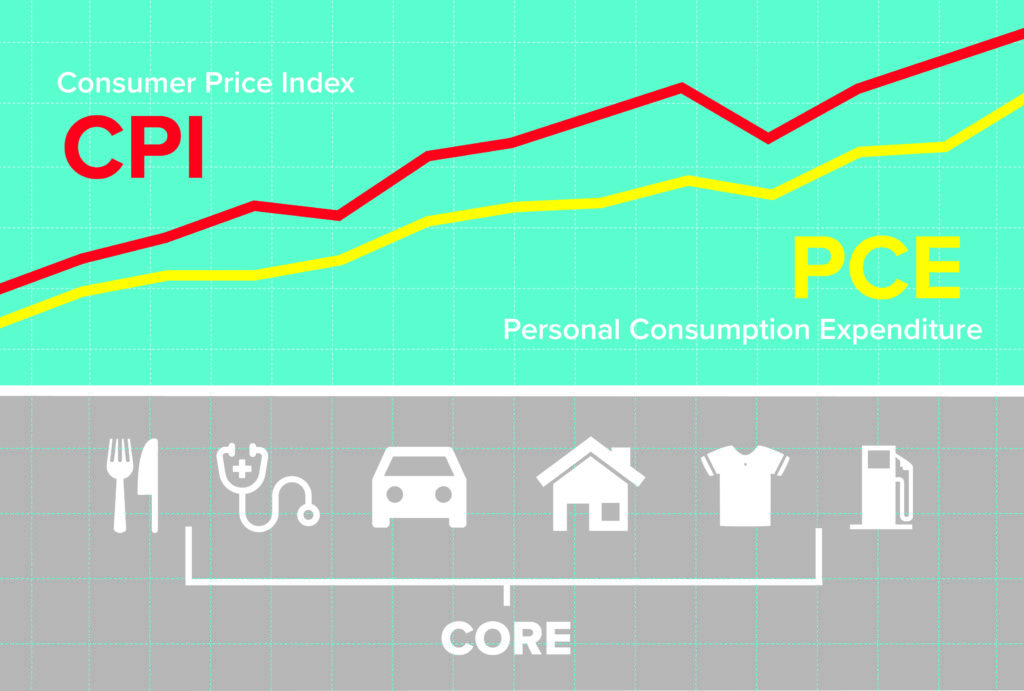

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The Consumer Price Index is calculated monthly by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. It includes several categories of everyday items that a typical household might buy: food, housing, clothing, health care, entertainment, education, and transportation. In constructing the CPI, the various items’ prices are weighted according to how much is spent on them by a typical consumer.

The CPI is the inflation measure most often reported in the media.

Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE)

The Personal Consumption Expenditure price index is calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis within the Department of Commerce. Like the CPI, the PCE price index contains an enormous range of goods and services. But it weights the various items according to their share in the national economic output (i.e., the value of all sales of goods and services), as opposed to just a typical household’s spending. It’s the inflation measure preferred by the Federal Reserve, and by Kocherlakota, who considers it the most meaningful measure.

In practice, the CPI and PCE price index tend to run closely together, Kocherlakota says, but the Federal Reserve’s preferred PCE inflation is generally, per year, about one half of a percentage point below the CPI. “When the Fed says it’s targeting a two percent inflation rate, that actually translates to 2.4 or 2.5 percent per year in terms of CPI.”

Core measures vs. headline measures

As defined above, the CPI and PCE price indices are what are called “headline” measures. But you might also hear references to so-called “core” versions of CPI and PCE inflation rates.

A core measure of inflation puts no weight on food or energy goods and services, including, perhaps most importantly, on gasoline prices. Policymakers and macroeconomists have generally found that core inflation is a more useful guide to the future evolution of headline inflation than is headline inflation itself. That’s because the fluctuations in food and energy prices tend to reverse themselves rapidly. For example, you might recall that in 2008, gas prices skyrocketed to over $4 per gallon in July and then fell to under $2 per gallon by the end of the year.

But Kocherlakota offers one cautionary note: if people begin to believe that high inflation will be a persistent, rather than a transitory, phenomenon, they will begin to act on that assumption, feeding a cycle of rising prices and wages. That’s the kind of crisis Kocherlakota hopes we can avoid with a better understanding of the current economic environment.

Q&A

Inflation today is roughly 5 percent. How concerned should we be?

The 5 percent figure refers to the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rate. I prefer to focus on the core PCE inflation rate (see “Defining inflation”), which was actually just over 3 percent in May. The Federal Reserve’s forecast calls for core PCE inflation to remain at 3 percent through the end of the year. I expect it may go up a little more, then come back down.

Is 3 percent large? For younger people, that’s significantly higher than where it’s been in the last 25 years. For those who remember the 1970s, 3 percent is small potatoes. The inflation rate ticked up into the double-digits during that period, and it took years for the Fed to bring it back down to 2 percent.

Two percent is the rate the Fed aims for. Why? It’s a way to balance out two problems. If people expect high rates of inflation, lenders will expect to be paid a very high interest rate in order to compensate them for the fact that the money they’re receiving is losing value over time. So if you had a ten percent rate of inflation in the late 1970s, then interest rates will be double digits, as they were. At the same time, if we have a low inflation rate, you’re going to have low interest rates, and that gives the Fed less room to maneuver.

Does it make a difference that inflation went up very quickly?

According to the Fed, inflation ticked up in recent weeks and months due to transitory factors. Used car prices, which went up dramatically, are a great example of a transitory driver of inflation; they won’t keep going up at that rate every month for the next year because the price increases were traceable to supply shortages, which, in turn, were traceable to COVID-19. You might even see them come down some. The fact that inflation has risen so rapidly is exactly the reason we might expect the drivers to be transitory.

So the rise in inflation is a short-term effect of the end of the pandemic?

That is absolutely the overriding factor. Consumer demand is outpacing the supply of goods and services. Everyone knew inflation was going to be high; the only question was how high.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t other factors. The extension of unemployment benefits mattered, but I don’t know how much. Those extensions do offer an incentive for people to be more selective in what jobs they’ll accept, which puts an upward pressure on wages and an upward pressure on prices.

But returning to the example of used car prices: that has nothing to do with unemployment insurance benefits; it’s just driven by supply-chain issues, traceable back to the pandemic, and to demand-side effects.

I went back and looked at the Fed’s discussions during the first SARS outbreak—which did not affect the United States materially—back in the early 2000s. And one of the things that was apparent was how much demand shot up in Asia after the pandemic was over. So what we’re seeing now was all forecastable.

How could this inflation blip, as you characterize it, become an economic crisis?

An inflation scare could influence people’s expectations going forward. If businesses and workers assume an inflation rate of greater than two percent when making wage determinations for the coming fiscal year, it can start to become self-fulfilling; workers will have to be paid more and, because of that, prices will have to go up. This is the cycle we saw in the 1960s and ’70s when rising inflation became baked into people’s expectations. This can become a big problem if we see it built into wage-setting practices and price-setting practices. Then what was a transitory phenomenon becomes a persistent phenomenon. That’s a much more complicated problem for the Federal Reserve and policymakers.

The money will soon be gone from the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package. Will that help bring down inflation?

Yes. That will bring down demand, which is one force behind inflation.

Is there anything the government or Federal Reserve can or should do to address inflation today?

I think the Fed is doing exactly the right thing. The big change at their recent meeting is that they announced that they now expect to raise interest rates by half a percentage point in 2023. It doesn’t lock them in to raising rates, but it sends a signal that inflation is coming a little hot, but they are ready to deal with it.

What keeps inflation expectations under control is that people agree with the Fed that this is a transitory phenomenon. And people agree with that because the Fed keeps talking their game— they will be willing to raise interest rates to keep inflation under control once the economy is back to full employment.

You’ve argued before that inflation has been too low. What’s the bright side of inflation?

A temporary inflation blip of the kind we’re seeing is a small price to pay for the increase in employment. If you cut demand, that means people don’t have jobs. The Fed is making the call, and the Congress has made the call, that we want to have jobs, and we’re willing to pay the cost of having slightly higher inflation for a short period of time. And I agree with that.

US housing prices have skyrocketed, with the median price of a house increasing more than 15 percent from May of 2020 to May of 2021. How much of an impact does the housing market have on inflation?

House prices have an asset side to them. These inflation measures are not directly driven by what’s going on with the price of a house, but it is an element of monetary policy. One of the goals of low interest rates is to drive up asset prices. If interest rates are low, people are motivated to move out of bonds and into other kinds of assets. In other words, it’s cheap to borrow in order to buy real estate, so houses will go up in value.

Read more

How the coronavirus recession will end

How the coronavirus recession will endUniversity of Rochester economics professor Lisa Kahn says the coronavirus recession is anything but typical.

What will it take to restore the economy after COVID-19?

What will it take to restore the economy after COVID-19?Narayana Kocherlakota, the Lionel W. McKenzie Professor of Economics at Rochester, offers his view on economic recovery during a pandemic.

A closer look at inflation

A closer look at inflationSimon Business School Dean Sevin Yeltekin addresses six key questions about inflation in the post-COVID-19 business world.