Here are a few things to know about the literary masterpiece that has exhilarated and confounded its readers for 100 years.

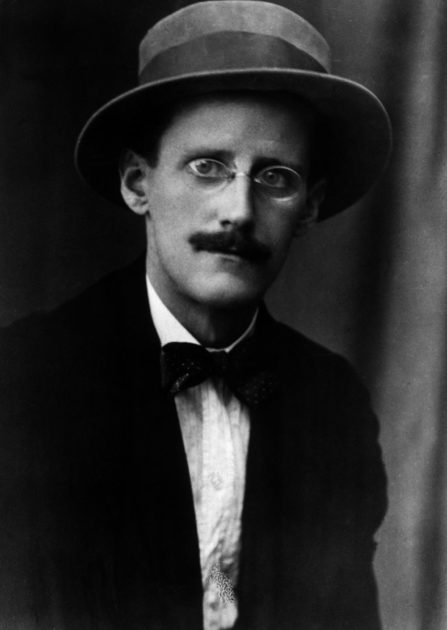

In the century since its publication, James Joyce’s Ulysses has been described as beautiful, overrated, experimental, pornographic, dull, and genius.

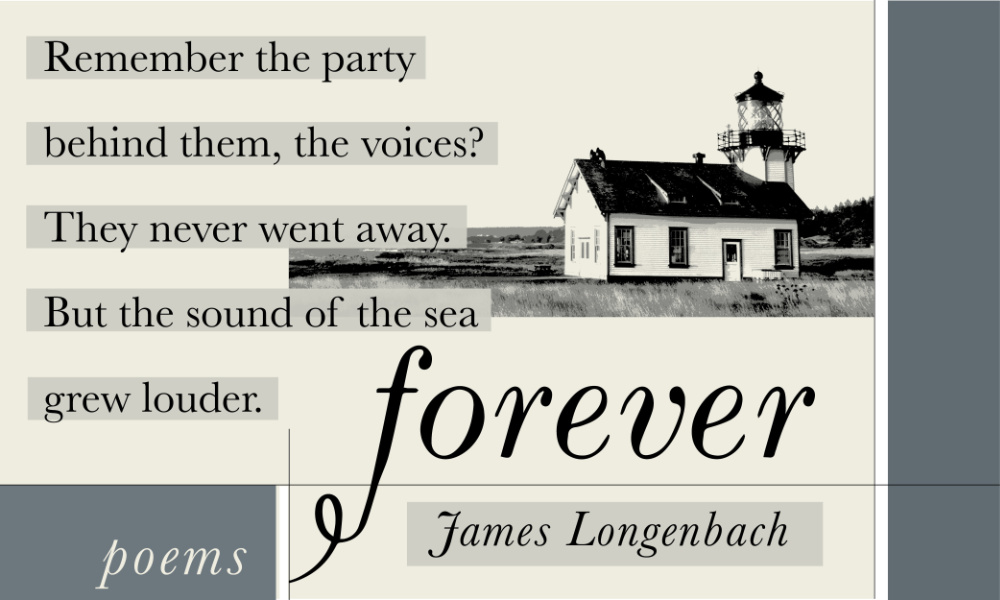

“It’s also a great leveler,” says James Longenbach, the Joseph Henry Gilmore Professor of English at the University of Rochester. He has taught the book since the late 1980s as part of various undergraduate and graduate courses on literary modernism.

“I studied with A. Walton Litz, a great Joyce scholar, and I realized that if I didn’t teach Ulysses, I was squandering that experience,” he says.

Based on insights from Longenbach’s years of reading, teaching, and writing about Ulysses, we’ve highlighted a few things you might not know about the 700-plus-page novel that regularly ranks among the greatest—and most challenging—English-language works of fiction.

What is Ulysses by James Joyce about? “Two things at once,” argues Longenbach, one of which is language itself.

Published in 1922, the story traces a single day, June 16, 1904, in the lives of several characters in Dublin, Ireland. The main protagonists include “everyman” Leopold Bloom, Stephen Dedalus (a young man—Joyce’s literary alter ego—struggling with the death of his mother), and Leopold’s wife, Molly.

Most of the novel follows Bloom as he traverses the city, endures an antisemitic tirade, crosses paths with Stephen, and ends his day back in bed alongside Molly, whose famous monologue concludes the novel.

But a plot summary doesn’t do the work justice. Here’s how Longenbach, in a 2013 article for The Yale Review, summed up Joyce’s most famous work:

Ulysses is two things at once. On the one hand, it is a realistic novel, an unrelenting exploration of the inner and outer lives of three major characters and a multitude of minor ones. On the other, it is an elaborate verbal confection, an intricately designed work of art that draws attention to its linguistic surface, sometimes at the expense of the very illusion of inner life that it also creates.

There is no definitive edition of Joyce’s Ulysses. But there’s a reason the “Gabler edition” may stand above most others.

Ulysses, which was initially serialized in the United States in The Little Review, “had no editor, no publisher that existed prior to the moment of its publication, no typesetter who understood English,” wrote Longenbach in The Yale Review.

The first edition was published in its entirety was in 1922 by Sylvia Beach, an American-born champion of Joyce and his work, as part of her Paris bookselling business Shakespeare and Company. Since then, more than a dozen versions have been published, many purporting to correct non-intentional errors and mistakes.

For his part, Longenbach has students read the version edited by Hans Walter Gabler and released in 1984, which attempts to produce an accurate and complete version of the book. That’s no easy task, however, given that Joyce wrote nearly a third of the work on the print proofs, notes Longenbach.

Pre-Gabler editions, for example, have Stephen Dedalus receiving a telegram that reads, “Mother dying come home father,” correcting the original manuscript’s “nother” to “mother,” assuming a typo. “The Gabler edition, though, says nother, as Joyce did originally, leaving readers to ponder this ‘error,’” says Longenbach. “Now, are there mistakes in Gabler? Yes, but fewer.”

The book’s chapters, which Joyce called “episodes,” are based on The Odyssey by Homer—but using the epic poem to interpret the work is misguided.

Ulysses is the Latinized version of the Greek name Odysseus, and the book’s eighteen episodes are loosely based on Homer’s epic poem Odyssey. So, that means Leopold Bloom is Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus is Telemachus, and Molly Bloom is Penelope, right?

Longenbach cautions readers against using the Homeric poem as a Rosetta Stone to decipher meaning. “In the critical history of Ulysses, attempts to find a key often only succeeded in turning Ulysses into a lock,” he says.

Instead, Longenbach invites readers to revel in the book’s panoply of literary and linguistic styles. These include the journalistic headlines interrupting the “Aeolus” episode; the florid, romantic language in “Nausicaa”; the stage directions in “Circe”; and Molly Bloom’s famous, mostly unpunctuated final soliloquy. Even the realism that characterizes the early episodes is a consciously crafted artifice, as in any novel, but that reality is thrown into high relief by the explosion of styles that follow.

Though he’s the target of antisemitism, protagonist Leopold Bloom is not really Jewish.

In the “Cyclops” episode, Bloom is the target of an antisemitic tirade by a cartoonish Irishman referred to as “the citizen.” To this assault, Bloom responds, “Your God was a jew. Christ was a jew like me.” He later admits he was only pretending to be Jewish: “So I without deviating from plain facts in the least told him his God, I mean Christ, was a jew too and all his family like me though in reality I’m not.”

In other words, Bloom is not really Jewish—nor does he consider himself to be Jewish, despite his father being a Hungarian Jew (one who converted to Protestantism before his son was born).

“You could fill a page with the evidence,” Longenbach says, who cites Bloom’s being baptized twice (once as a Catholic, once as a Protestant) as well as his not being circumcised. “The first time we see him he’s cooking a pork kidney!” he adds. “But all of this information is scattered and buried and easy to overlook, so we as readers are allowed to make the same mistake as the citizen.”

Although Ulysses is now often identified with Dublin, Joyce was no Irish nationalist.

The book has come to be identified closely with not only Dublin, but also Ireland. For example, June 16 is known as Bloomsday, an annual commemoration and celebration of the life and works of Joyce. Named after protagonist Leopold Bloom, the day is marked in Dublin (and elsewhere) with various celebrations, such as participants retracing Bloom’s route around the city and marathon readings of the novel.

Yet Joyce’s feelings about Ireland were complicated. An unabashed anarchist, “he thought it was an extremely backward and closed culture because it was pinched between the British Empire and the Catholic Church,” explains Longenbach. “And he abhorred the teaching of Irish as well as Irish nationalism, which he considered racist and sexist, like all nationalisms he knew.”

The novel influenced other modernist writers, including T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf.

“It’s important to remember that Ulysses begins to be really influential long before it was published in 1922,” Longenbach says.

Take, for example, T.S. Eliot, a contemporary and an admirer of Joyce’s, and one of modernism’s major writers. Heavily influenced by Ulysses and published later that same year, Eliot’s poem The Waste Land is more than 400 lines long and similarly abounds with references and allusions.

Yet Longenbach doesn’t want students bogged down in the poem’s annotations and explanations: “I’ve taught The Waste Land probably a thousand times, and I’ve never mentioned anything but form. You need to feel the multiplicity of sources, the weirdness coming in. But ultimately every part of that poem is lyrically pure—what matters is how it sounds.”

Another leading modernist writer, Virginia Woolf, publicly praised Ulysses while criticizing the book as “pretentious” and “a mis-fire” in her diaries and letters.

Among her best-known works is Mrs. Dalloway, which details a day in the life of the protagonist and several others in post–World War I England. Published in 1925, the novel is “unbelievably beautiful,” says Longenbach, but also “unthinkable without the precedent of Joyce.” Both novels explore their characters’ interiority while highlighting the importance of the seemingly inconsequential. “Except that Mrs. Dalloway associates that with femininity, culturally speaking, to a degree that Ulysses does not,” Longenbach says.

Is Joyce’s Ulysses hard to read? Yes, but don’t let that stop you.

The book is definitely worth reading in Longenbach’s estimation.

“After all these years of teaching it, I still notice things I hadn’t before,” Longenbach says. And although the text rewards readers, students, and scholars alike, it will almost inevitably frustrate them, too.

He adds, “At a certain point, you’re going to want to take the book and throw it across the room. That’s OK. It’s part of the reading process. It’s just that Ulysses might force you to confront that feeling more than other texts.”