On April 14, 1865, Albert Barrett, a member of the University’s Class of 1869, was in Ford’s Theater, celebrating his birthday two days before. His seat in the balcony box immediately opposite President Lincoln’s afforded him a clear view of the Lincoln assassination.

Witnessing the Lincoln assassination

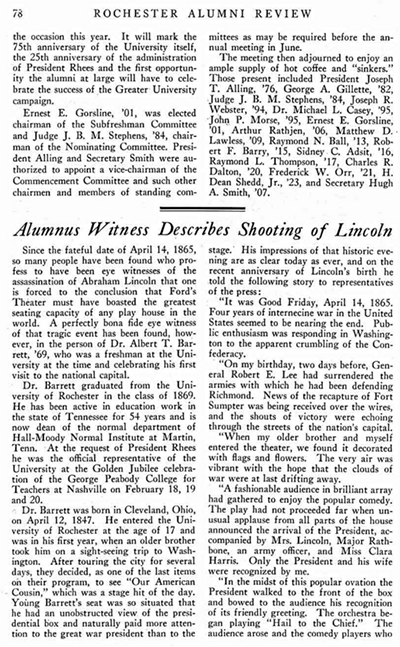

In the February-March, 1925, issue of Rochester Review, he recalled the experience. “The crack of the gun was the first intimation any one save the murderer had of the horrible crime being enacted,” he recalled. And while legend has it that Booth cried out “Sic semper tyrannis” as he fled the theater, Barrett heard no exclamation: “…no halt was made that could be seen, no word spoken that the audience could hear. Despite his stage antecedents, it was no time for classical quotations and rhetorical gesticulation.”

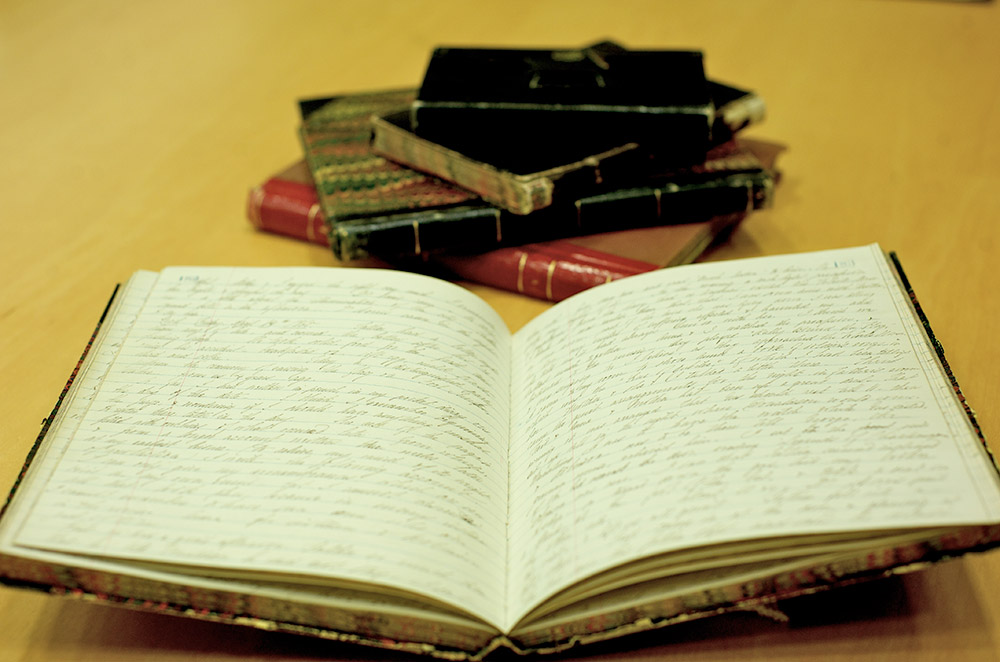

Throughout the Civil War, Fanny Seward, daughter of Secretary of State William Henry Seward, kept a diary of her life in Washington, D.C. On the night of Lincoln’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth, a co-conspirator, Lewis Powell made his way into the Seward home. He attacked Secretary Seward—who was bedridden, recuperating from serious injuries sustained in a carriage accident nine days before—and four other men in the house, including Seward’s sons Frederick and Augustus.

Fanny describes the harrowing scene: “I do not remember how [Powell’s] face looked, his arms were both stretched out, he seemed rushing toward the bed. In the hand nearest me was a pistol, in the right hand a knife. I ran beside him to the bed imploring him to stop. I must have said “Don’t kill him,” for father wakened, he says, hearing me speak the word…”

All the injured survived. Powell, who also used the surname “Payne,” was captured the next day at the boarding-house home of Mary Surratt and was executed in July 1865, along with the other convicted conspirators in the Lincoln assassination. On April 26, Booth was found hiding in a barn in Port Royal, Virginia, and was fatally shot by a Union soldier.

Fanny Seward’s diary, along with other official and personal papers of the Seward family, are held by Rush Rhees Libary. An online archive of the family papers launches on April 13.

First-hand accounts of the Lincoln assassination

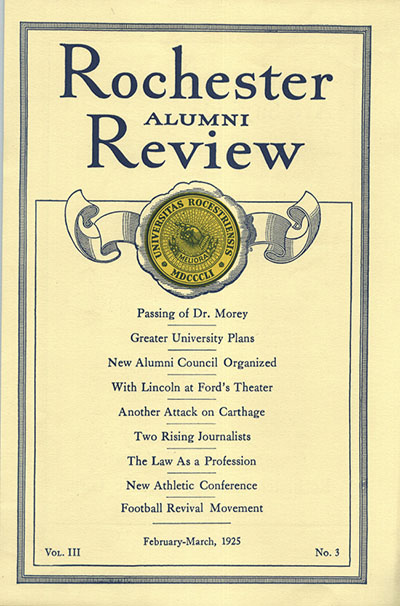

Albert Barrett: “Alumnus Witness Describes Lincoln Assassination,” Rochester Review, February-March 1925

Albert Barrett: “Alumnus Witness Describes Lincoln Assassination,” Rochester Review, February-March 1925

“It was Good Friday, April 14, 1865. Four years of internecine war in the United States seemed to be nearing the end. Public enthusiasm was responding in Washington to the apparent crumbling of the Confederacy.“On my birthday, two days before, General Robert E. Lee had surrendered the armies with which he had been defending Richmond. News of the recapture of Fort Sumpter was being received over the wires, and the shouts of victory were echoing through the streets of the nation’s capital.

“When my older brother and myself entered the theater, we found it decorated with flags and flowers. The very air was vibrant with the hope that the clouds of war were at last drifting away.

“A fashionable audience in brilliant array had gathered to enjoy the popular comedy. The play had not proceeded far when unusual applause from all parts of the house announced the arrival of the President, accompanied by Mrs. Lincoln, Major Rathbone, an army officer, and Miss Clara Harris. Only the President and his wife were recognized by me.

“In the midst of this popular ovation the President walked to the front of the box and bowed to the audience his recognition of its friendly greeting. The orchestra began playing ‘Hail to the Chief.’ The audience arose and the comedy players who were on the stage at the time stood silent until the music ceased.

…

“The play was resumed where it had been interrupted by he arrival of the President. Nothing unusual occurred as the play proceeded through the first and second acts, until the second scene of the third act began.

“From where I sat in the balcony box immediately opposite, every member of the President’s party was plainly visible. Suddenly a man not before noticed, but who later proved to be J. Wilkes Booth, rushed to the front of the President’s box, brandishing a dagger. Major Rathbone caught him by the coat. Booth turned upon him and struck him on the arm with the dagger, inflicting a serious wound.

“In jumping to the stage some ten feet below, the assassin’s spur caught in the folds of the flag which draped the front of the box. He fell heavily on one leg, fracturing it; however, he rose and hobbled rapidly across the stage. Then he disappeared from the sight of those in the theater.

“That is all anyone in the theater could see. Subsequently it developed that Booth had crept up the stairway to the balcony, entered a short, narrow hallway back of the presidential box and opened the box door. He was then immediately behind the president, who sat in a rocking chair facing the stage.

“The crack of the gun was the first intimation any one save the murderer had of the horrible crime being enacted. The head of Lincoln fell slightly forward, his eyes closed. He never regained consciousness. It seemed less than a minute before Booth had fled. He was shot to death near Fredericksburg, Va., we learned later.

“It is said that Booth stopped, faced the audience and shouted from the stage ‘Sic semper tyrannis’ (the motto of Virginia.) This must be false, for no halt was made that could be seen, no word spoken that the audience could hear. Despite his stage antecedents, it was no time for classical quotations and rhetorical gesticulation. His one thought was to escape.

“Lincoln was carried to a private house across the street, where he died the next morning. Thousands of us watched for hopeful signs before that house in Tenth Street.

“In the morning of the fatal day, as Lincoln was dying, I walked to the train, preparatory to leaving Washington. The city was densely wrapped in mist, as with the drapery of mourning. All hearts seemed chilled with the spell of dread and fear. Men would meet and pass without greeting.

“Many years have come and gone, yet whenever I visit Washington, where law and justice are supposed to be indigenous, my first impression is not the glory of American institutions and statesmanship, but rather the brutal assassination of Abraham Lincoln.”

Fanny Seward: “I remember running back, crying out ‘Where’s Father?’”

Lincoln and His Circle: Browse the Fanny Seward Diary online

Good Friday. April 14th 1865.

I saw that Father seemed inclined to sleep—so turned down the gas, laid my book on a stand at the foot of the bed, & took a seat on the other side.…I do not remember hearing voices outside, but something led me to think that Fred was there with some one else. It occurred to me that he might have some important reason for wishing to see Father awake. Perhaps the President was there, or had sent over. I did not stop to see if Father wakened thoroughly, but hastened to the door, opened it a very little, and found Fred standing close by it, facing me. On his right hand, also close by the door, stood a very tall young man, in a light hat & long overcoat. I said “Fred, Father is awake now.” Something in Fred’s manner led me at once to think that he did not wish me to say so, and that I had better not have opened the door. This confused me, & looking around I was glad to see Father going to sleep again. Holding the door as I did, I know the man could not see my father at all, nor could Fred, I think. I do not remember what Fred said to me. The man seemed impatient, & addressing me in a tone that struck me at once as much more harsh & full of determination than such a simple question justified, asked “Is the Secretary asleep.” I paused to look at my father, He replied “Almost.” Then Fred drew the door shut very quickly. I sat down again. I had no means of telling the errand of the man. I fancied some one had sent him—that he was, perhaps, a messenger from the telegraph office. Very soon I heard the sound of blows—it seemed to me as many as half a dozen—sharp and heavy, with lighter one’s between. There had been an interval of quiet. I did not fully connect this with the person I had seen.

…

I saw that two men came in, side by side. I was close by the door, & the one nearest me, was Fred. The side of his face was covered with blood, the rest very pale, his eyes full of intense expression. I spoke to ask him what was the matter,—he could not answer me. On his right hand was the assassin. I do not remember how his face looked, his arms were both stretched out, he seemed rushing toward the bed. In the hand nearest me was a pistol, in the right hand a knife. I ran beside him to the bed imploring him to stop. I must have said “Don’t kill him,” for father wakened, he says, hearing me speak the word kill, & seeing first me, speaking to some w one whom he did not see—then raised himself & had one glimpse of the assassin’s face bending over, next felt the blows—and by their force (he being on the edge of the bed, where fear of hurting his broken arm, had caused him to lie for some time) was thrown to the floor. I cannot remember seeing him—nor seeing Payne—wh go around the bed—but Anna was in the room and saw it.

…

Then I looked about and saw, first, what I had seen before I think, but more fully now, three men struggling beside the bed. I knew who they all were then. I could not tell the next day. But they were Fred & Robinson & the assassin—next I saw all the familiar objects in the room, the bureau, the little stand, the book I had been reading, all looked natural. Then I knew it was not a dream. I remember pacing the room back & forth from end to end—screaming.

…

I have a very indistinct recollection of the next moment, when I seemed to meet Mother on one side, and Anna on the other, both saying “What is the matter,” and I said something about the man, (Payne) who came out struggling with some one, I afterwards learned it was Augustus. I think I saw the assassin stab Hansell, as he, the assassin rushed headlong down the stairs. I do not know just when—but I remember in the hall with Mother and Anna asking me what happened, my saying “Is that man gone,” and they said “what man.” The first recollection I have of seeing Augustus—except when the assassin broke away from him, was with his forehead covered with blood. It seemed to me that every man I met had blood on his face.

…

I remember running back, crying out “Where’s Father?,” seeing the empty bed. At the side I found what I thought was a pile of bed clothes—then I knew that it was Father. As I stood my feet slipped in a great pool of blood. Father looked so ghastly I was sure he was dead, he was white & very thin with the blood that had drained from the gashes about his face & throat. Fred was in the room till after Father was placed on the bed. Margaret says she heard me scream “O my God! Father’s dead.” I remember that Robinson came instantly, &: lifting him, said his heart still beat—& he, with or without aid, laid him on the bed. Nothin Notwithstanding his own injuries Robinson stood faithfully at Father’s side, on the right hand—I did not know what should be done. Robinson told me everything—about staunching the blood with cloths & water. He applied them on the right side, & I, kneeling on the bed, on the left, put them on a wound on that side of the neck. Father seemed to me almost dead, but he spoke to me, telling me to have the doors closed, & send for surgeons, & to ask to have a guard placed around the house.

…

A clot of blood upon father’s chest, which I had taken for a stab, was found to be only blood that had collected there outside. We were assured that no artery was severed, & the wounds were not fatal.