How late capitalism is the underrecognized monster lurking in modern American horror.

“Sometimes I wonder what it was exactly, that led me to pull The Dead Zone by Stephen King off of my parents’ bookshelf when I was in fourth grade,” says Jason Middleton. “It was the first ‘grown-up’ novel I ever read. There were certainly parts of it that I found kind of upsetting, but also magnetic. It almost felt as if the world was opening up in a new way.”

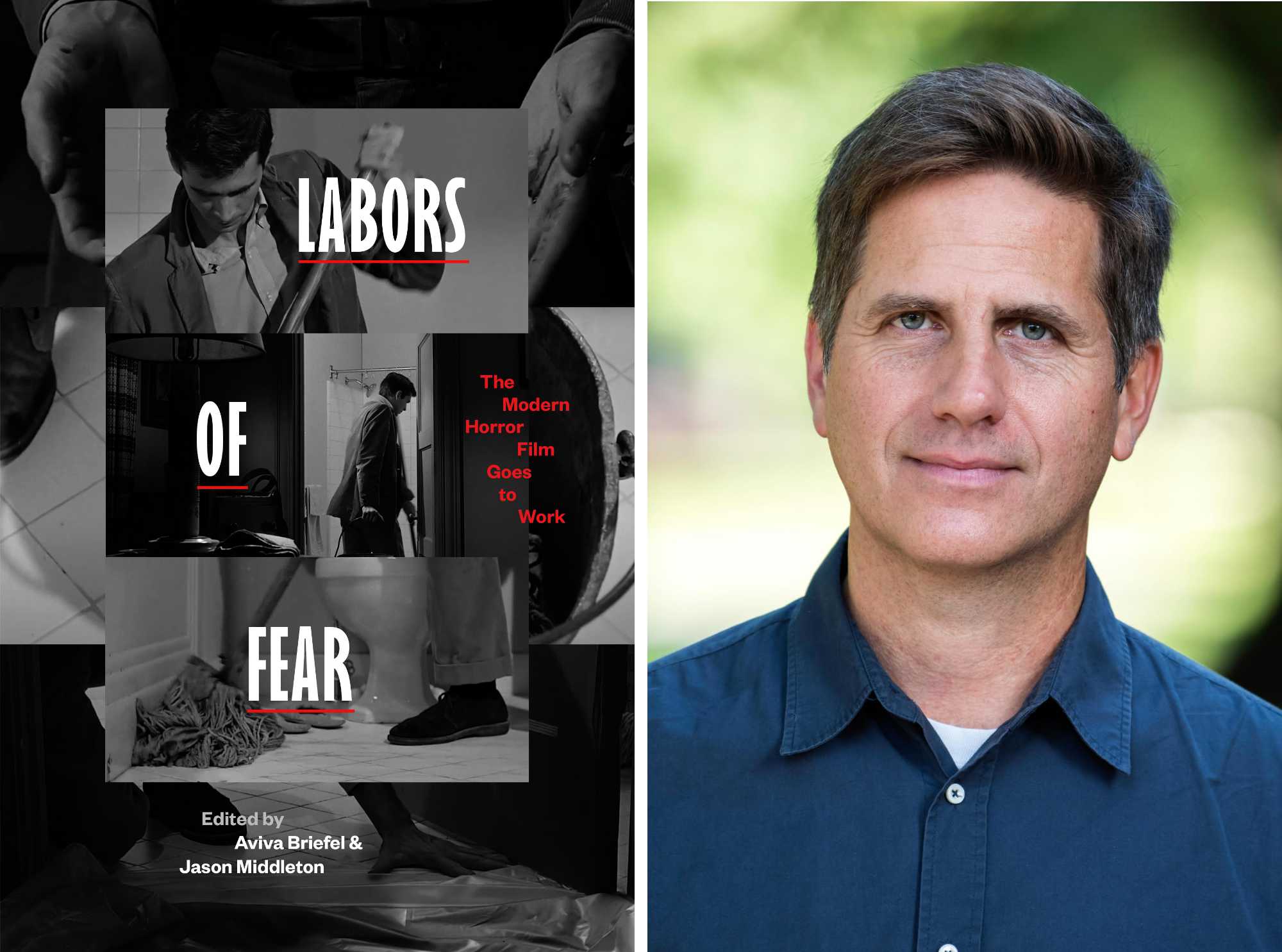

Middleton is an associate professor of English and of visual and cultural studies at the University of Rochester. He also directs its film and media studies program. His captivation by King’s novel led to a lifelong love of horror films. Although horror is just one of the film genres Middleton has immersed himself in—both as a fan and a scholar—it’s a genre whose appeal he thinks is especially durable.

In horror, “normality is threatened by a monster,” he says. “What’s so wonderfully expansive about the horror genre is that the monster keeps forming and reforming in relation to the fears and anxieties of its time. And on the flip side, normality, and the depiction of normality, keeps evolving and changing based on the historical period as well.”

Work as the American nightmare

There have been some clear trends. In the post-World War II era, the monster was often a stand-in for anxieties about the atomic bomb. During the feminist movement of the 1970s, the monster often suggested anxieties about female power and female bodies.

That critique has extended into a new era—late capitalism, a phrase coined to describe a world of globalized commodification that’s both unsettling and absurd. The essays focus overwhelmingly on 21st-century horror films. Those depict a world of economic precarity and a hollowed-out middle class that make up “a new ‘normality’” of survival, or of just getting by. And even that bleak environment is vulnerable to new monsters that threaten what stability protagonists have been able to muster—or that they are striving to attain in the first place.

In Labors of Fear: The Modern Horror Film Goes to Work (University of Texas Press, 2023), Middleton has joined with Aviva Briefel, who teaches literature and film at Bowdoin College, to make the case that there’s been another kind of monster lurking in American horror films all along: the post-industrial world of work.

In the essay collection, which they coedit, Middleton and Briefel suggest that ambivalence about work is a theme that has roots stretching back to classic horror, when it usually came in the form of the mad scientist. In modern horror films, starting roughly in the 1970s, ambivalence evolved into a fuller critique. Middleton and Briefel describe the critique as reflecting “social fears and anxieties that took root in the 1970s and 1980s in response to deindustrialization, automation, globalized labor, union busting, and rising income inequality.”

An easy example is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, a pathbreaking film that’s 50 years old this year. Rural, unemployed slaughterhouse workers are never shown performing slaughterhouse labor, but are shown “repeating the trained motions of this labor upon their human victims,” they write.

New categories of uncompensated work

Middleton is especially interested in forms of uncompensated work, which he argues fall disproportionately on groups that are already marginalized. He isn’t just talking about such uncompensated labor as housework or family caregiving. In his own contribution, “No Drama: Emotion Work in Midsommar,” Middleton explores “emotion work” in the 2019 film directed by Ari Aster.

He describes emotion work as “suppressing and modifying, and maybe not expressing one’s own feelings in order that a spouse or partner has the kind of optimal experience that they themselves expect to have in the relationship.” It has a long history in the quest of women to get by but has proven resilient even as women have achieved greater economic independence.

Midsommar (2019) depicts the arduous efforts of a 20-something female protagonist, Dani, to hold onto her relationship with her distant and disengaged boyfriend, Christian. The couple attends a summer festival in Sweden that turns out to be an annual ritual of a murderous cult.

Its horrors mirror Dani’s labors in preserving her attachment to Christian. But she also attains a level of power within the cult, and the film’s cathartic ending shows Dani ending the relationship by sacrificing Christian.

It’s actually a breakup story, Middleton explains. But in showing the slow, laboriousness process in which Dani comes to recognize Christian’s neglectfulness, it’s the inverse of many lighter breakup films. “It’s kind of the horror movie version of a breakup film like Eat Pray Love or Under the Tuscan Sun,” he says. “The semantic elements are mostly the same—travel, exotic location, meeting different people, food, all of these things. But whereas in those films, the work of a breakup is frictionless and fulfilling and idealized, Midsommar uses the horror genre to instead express the work of a breakup as just agonizing, laborious, and painful—and ultimately, in the end, cathartic.”

The horror of stagnation—and of leisure

The essays in the collection also demonstrate how the experience of economic precarity can differ along racial lines. Briefel’s essay, for example, is subtitled “The Hard Work of Leisure in Jordan Peele’s Us.”

“In a 2019 interview for Vanity Fair, Jordan Peele explained that one of his objectives in the film Us was to represent Black leisure,” Briefel begins. “Yet relaxation is a major source of horror in the film.” Us shows a Black family living with a constant threat of merely letting their guard down.

In another essay, Mikal Gaines, an assistant professor of English at Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, coins a subgenre of “Buppie horror,” which reworks the conventional home-invasion thriller. Lakeview Terrace (2008) is an archetype, Gaines explains, of a subgenre that “seems to say that entry into a rarified class status historically reserved for whites must be paid in blood.”

For many white Americans, however, the threat is losing what they have—or living with the dread of having already lost. Middleton’s colleague at Rochester, Joel Burges, finds in David Robert Mitchell’s 2014 film It Follows a depiction of “the precarity of white working-class identity.” The film shows a group of young adult friends in a desolate and stagnant postindustrial Detroit. It’s a reworking of the stalker films of the 1970s and ’80s, explains Burges, like Middleton, an associate professor of English and of visual and cultural studies. It Follows adheres to the slasher convention of punishing people for sexual acts. Sexual encounters between the characters—men as well as women, in this film—infect characters with “It,” a stalker who lurks after them, and takes changing forms, but always of mangled middle- and working-class white bodies.

In these bodies, however, Burges found something beyond the slasher convention in which sex equals death. In It Follows, the work of getting by literally takes place mostly in low-level, dead-end service occupations that fill the young adults with dread to have. There’s emotion work, in other words, in surviving the bleak landscape through which “It” stalks victims. “Dread is slow,” Burges writes. “Its menace bears down on you with steadily intensifying pressure that never relents.”

Horror films in the post-COVID era

When Middleton and Briefel got started on their project, COVID-19 was sweeping across the globe. No one knew at the time just how much the pandemic would transform the world of work. Have these changes started to play out in horror films? And if so, how?

Says Middleton: “Something that I noticed during the last few years is that some really interesting horror movies take place not only entirely in a house, or entirely within an enclosed space, but entirely just a person and their laptop. For example, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021). The whole film is just from the perspective of an isolated teenage girl on her laptop, as she’s on it every night to do these internet challenges that grow increasingly dangerous and threatening as she does them.

“It’s just the horrific experience of being on the internet on your laptop all the time.”