The latest Nobel Prize in Literature laureate has unexpected ties to the University’s literary translation press.

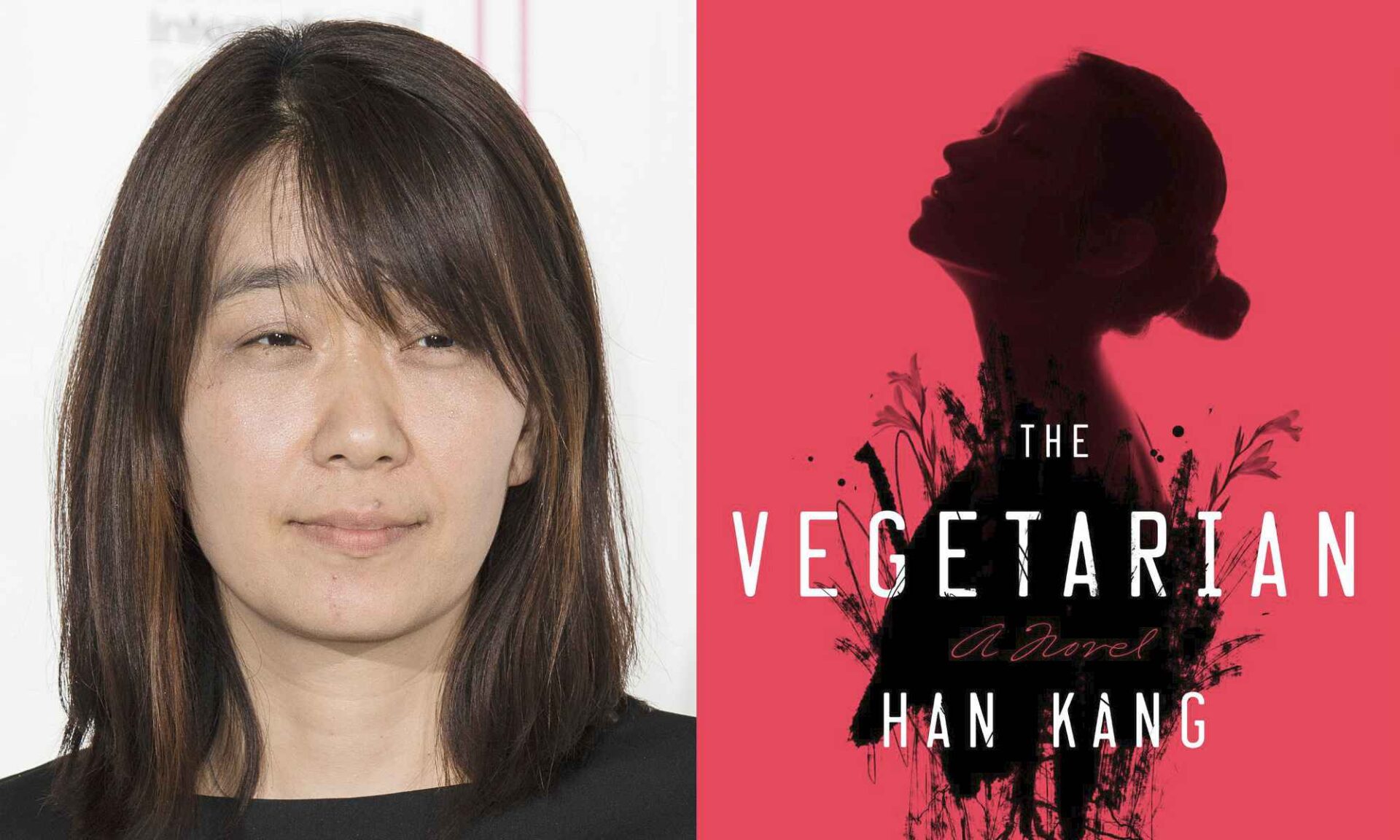

South Korean poet and novelist Han Kang has won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature for a poetic and unsettling body of work that “confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life,” according to the Nobel committee.

“Before my wife turned vegetarian, I’d always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way,” reads the opening line of The Vegetarian, about a woman who believes she is turning into a plant, first published in South Korea in 2007 and translated into English in 2015.

The novel continues:

To be frank, the first time I met her I wasn’t even attracted to her. Middling height; bobbed hair neither long nor short; jaundiced, sickly-looking skin; somewhat prominent cheekbones; her timid, sallow aspect told me all I needed to know.

Tracing a woman’s descent into mental illness and neglect by her family, The Vegetarian became the first Korean-language novel to snag the International Booker Prize for fiction. That was eight years ago and the honor put Han, now the author of 13 novels and novellas, on the map for international audiences, making her a viable Nobel Prize contender.

Of course, it’s the work of literary translators that make international literature accessible to a wider audience. That’s where Rochester’s connection to this year’s Nobel laureate starts, although not in the way you might expect.

Chad Post, who heads up Open Letter, the nonprofit, literary translation press at the University of Rochester, rejected Han’s The Vegetarian when her translator originally offered it to the press.

“There are a lot of other books that do the same thing, but in a more interesting way,” Post explains his lack of interest. Instead, he says, he prefers the works of two other Korean authors, Bae Suah and Ha Seong-Nan.

“I think, on a stylistic level, they’re more sophisticated,” he says.

But unlike twelve publishing houses that are still kicking themselves hard for turning down J.K. Rowling when she came knocking with her first Harry Potter manuscript, Post remains sanguine. “If you start doubting yourself like that, then you get into a weird mind space where you ask yourself ‘What are you publishing for? Are you publishing because you think this will win a prize? Or are you publishing because you think this is an amazing author?’” says Post.

A translation controversy

Choosing an author’s work to be published in translation comes down to several crucial factors beyond the quality of the work itself. Just as important, says Post, who also oversees the editorial activities at Dalkey Archive Press, is the translator who is attached to a particular book or author.

When it came to Han’s translator, Deborah Smith, he was thrown by a style that didn’t feel consistent across the translated manuscript of The Vegetarian. To be honest, he didn’t really love the book either.

Later, controversy ensued when critics noticed striking deviations from Han’s original Korean text compared to Smith’s English translation, which now suddenly had a British-Victorian tinge. Tim Parks, writing for The New York Review of Books, was the first to raise red flags about the translation in his article “Raw and Cooked,” mincing no words: “Sometimes this mix of the uptight and the colloquial creates an awkwardness at the limits of comprehensibility,” Parks lamented.

Smith, who is English, admitted freely that she had learned Korean only three years earlier, largely through translation work.

The popularity of Han’s novels, particularly The Vegetarian, got her translated into Swedish, which is likely the translation the Nobel judges read. “Of course, I don’t know what exactly they were reading,” notes Post. “As Anglophone readers, we just know what Han Kang sounds like via the lens of Deborah Smith.”

Admittedly, translating literature is always a balancing act: remain too literal and one risks missing clever word puns, subtle innuendo, sly satire, or meaning that is derived from a backdrop of shared experiences, understood only in a specific country or region. But stray too far from the text and you end up writing your own work, unfaithful to the original.

In the end, Post says, the public spat over Han’s (mis)translated work, which even spawned academic inquiry, shone a light on issues that needed to be addressed.

“It did elevate the conversation about what constitutes a good translation,” says Post.

In another twist, Open Letter’s rejection probably proved fortuitous for Han, admits Post. Hogarth, a bigger US publisher (and a Penguin Random House imprint) ended up taking on The Vegetarian instead.

“If we had published it, it probably wouldn’t have won any prizes,” Post says. “But coming from a big press with big money behind it, it was able to get a lot more attention.”

South Korea’s eyes on the Nobel Prize

While Han was by no means the favorite to win this year’s Nobel Prize, her success wasn’t a matter of chance.

About a decade ago, South Korea’s government went to work on showcasing Korean culture to the world, aiming for nothing less than the top literary award in the world. Playing the long game, the Korean Ministry of Culture started the Literature Translation Institute (LTI) of Korea, a well-funded program to help promote Korean literature, and established training for professional translators. The institute’s efforts ran the gamut from funding complete translations of literary works (even before they had a publisher), to promotional grants for Korean writers to tour abroad, to grants for international editors to visit Korea.

In 2016, The New Yorker asked provocatively, “Can a big government push bring the Nobel Prize in Literature to South Korea?”

We now know the answer.

Speaking of LTI Korea’s generous funding: Post was one of their invited editors. During a trip to Seoul in the winter of 2014, he not only met Deborah Smith, Han Kang’s eventual translator, but also numerous other Korean authors, agents, and publishers. As a result, Open Letter signed on the English translation of A Greater Music, by Korean author Bae Suah, which became the first book in the press’s Korean Series, funded by LTI Korea. Incidentally, the translator for that project was Deborah Smith.

As an aside, Post says it really wasn’t Korean literature (until now) that ended up attracting worldwide attention. Instead, the cultural phenomenon of K-pop—which hit stratospheric heights in 2012 with the international mega hit “Gangnam Style” by rapper Psy—became Korea’s strongest cultural ambassador, more so than any literary prize could hope to attract.

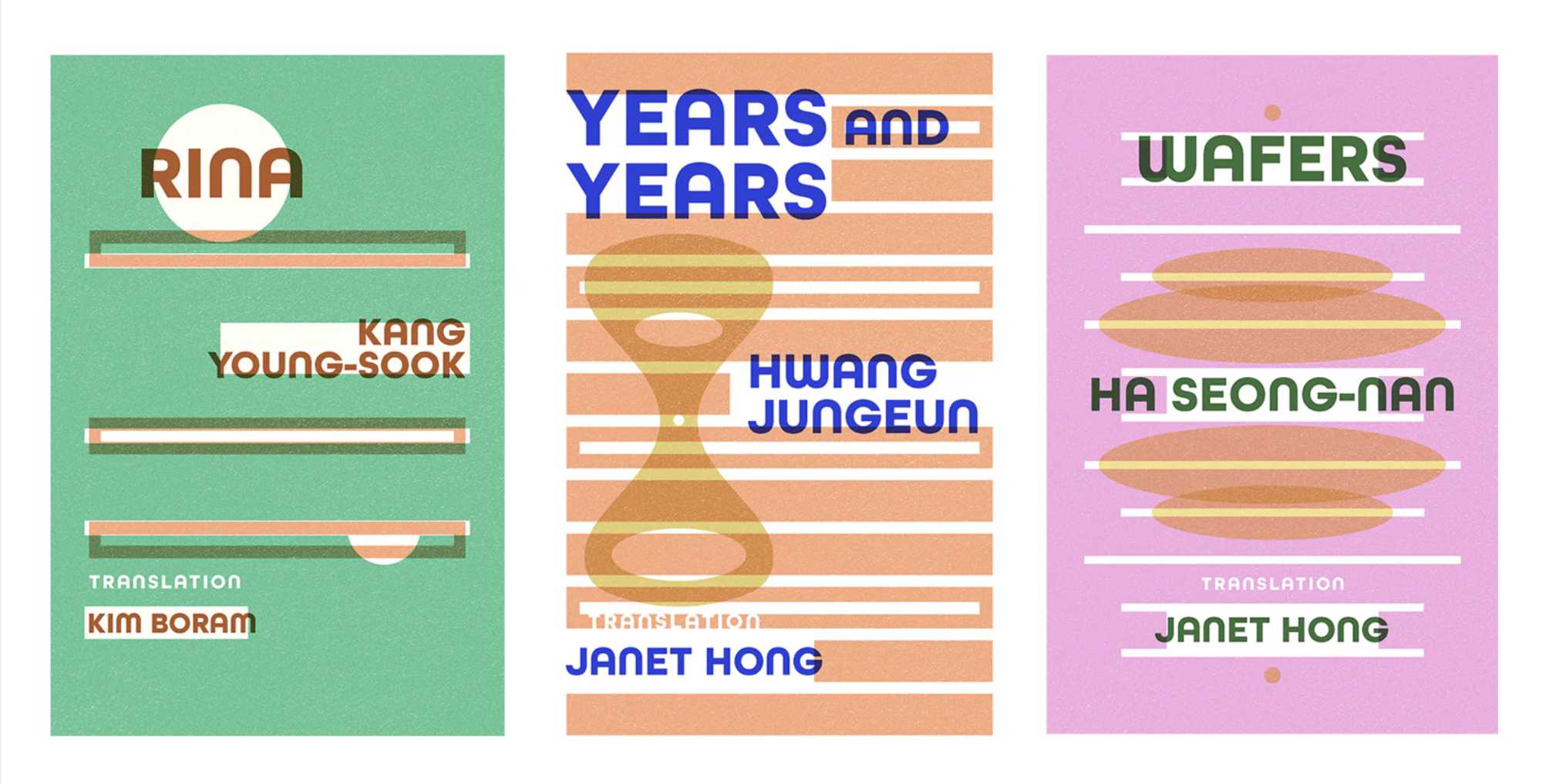

Yet, Korean literature is a force to be reckoned with. Today, Ha Seong-Nan is Open Letter’s best-known Korean author. “Her stories are psychologically creepy, and so gripping and weird in all the right ways,” says Post, who admits that he prefers the works of both Ha Seong-Nan and Bae Suah over those by Nobel Prize laureate Han.

“In terms of what they contribute to international literature, Ha and Bae are more challenging and innovative, leading to more original, better books,” says Post.

Including a so-called Translator’s Triptych of three titles, selected by translator Janet Hong (published this summer), Open Letter now has more South Korean contemporary female writers in English translation than any other press.

Was it a stupid move to reject Han?

“Not the first time that has happened,” Post laughs. “I mean, we stand by our editorial vision.”

The day before the announcement from Stockholm, The Guardian had picked Chinese author Can Xue, another translated author of Open Letter, as the most likely winner.

“We have a ton of authors who could or have been in the running for the Nobel Prize,” Post says. “You just you can’t win them all.”