Open Letter’s Chad Post on discovering the Norwegian author for English audiences—and the importance of foreign translation presses today.

Norwegian author and playwright Jon Fosse, the recipient of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature, published his first novel in 1983. By the mid-1990s, his literary star had firmly risen in Europe; yet it would take another decade for him to appear on the Anglophone horizon.

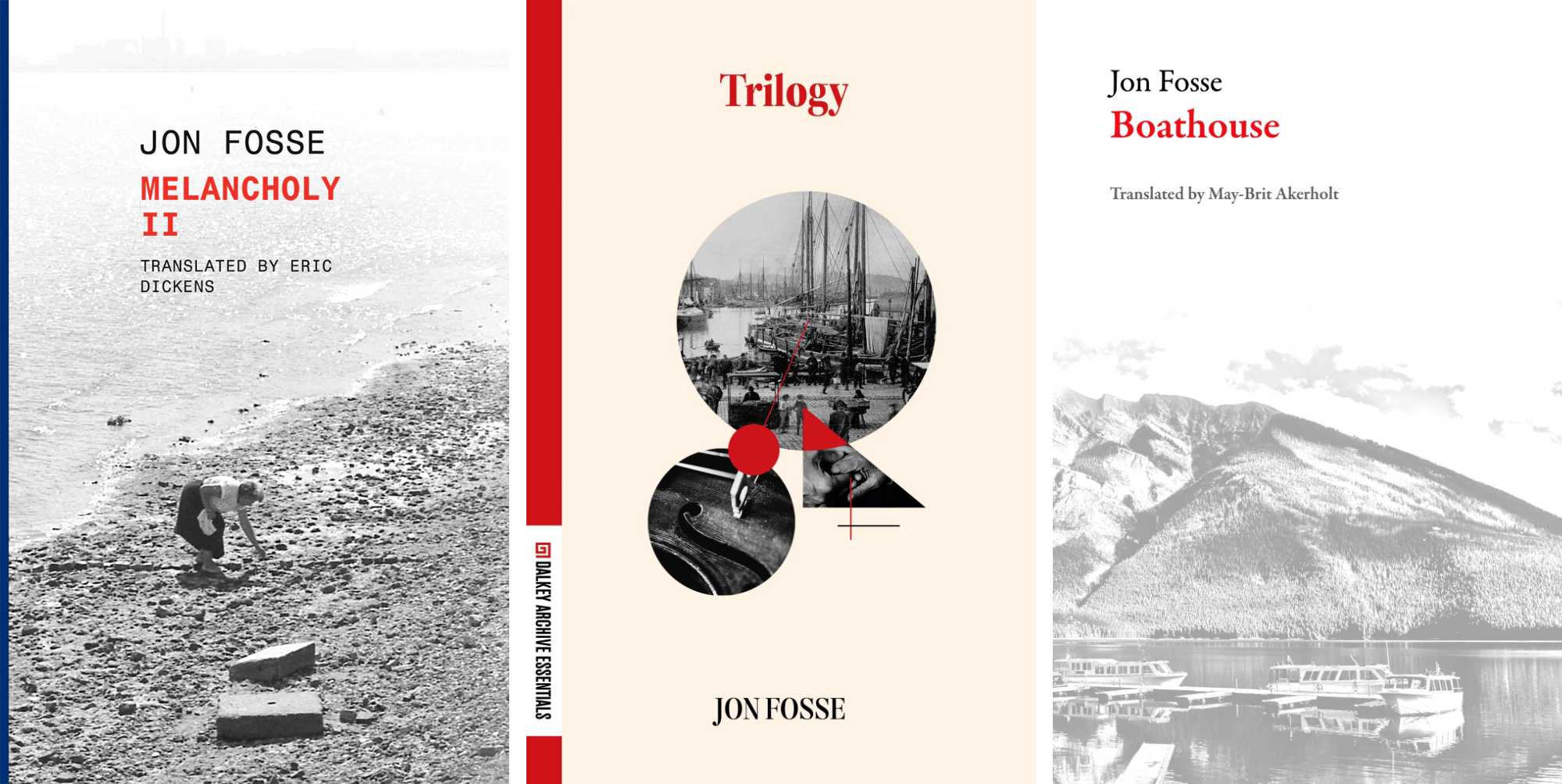

That’s when Chad Post, then an editor at Dalkey Archive Press—which at the time published the majority of translated books in the United States—first received a sample translation and the summary of Fosse’s 1995 book Melancholia I, its original title. Today, Post oversees the editorial activities at Dalkey while also heading up Open Letter Books, the nonprofit, literary translation press at the University of Rochester.

It didn’t take much to convince Post.

“I read the sample, loved it, brought it to the publisher, and we acquired the book,” he recalls. “I was really enamored with the writing style, the prose, and the mentality of the protagonist’s mind that is dissolving over the course of the book.”

Published in 2006, Melancholy became Fosse’s first foray into the North American market—and Dalkey, Post notes proudly, was the first press in the world to publish the Norwegian author in English.

Yet, the book was by no means a slam dunk. Sales were initially modest. But that, says Post, was in line with the press’s long-term strategy of investing in quality authors who would slowly gather steam as their international reputations grew.

“Essentially, it’s waiting for a Nobel Prize,” says Post, not entirely joking. Incidentally, Fosse novels sold out in the US on Thursday within hours of the early-morning announcement from Stockholm.

Over the next 18 years, Dalkey went on to publish six more books by Fosse. Since 2008, Post has also been the publisher of Rochester’s Open Letter, which is dedicated to increasing access to world literature for English readers. Open Letter is now one of only about a dozen or so US presses that publishes foreign works translated into English.

Issuing about ten translated titles each year and running an online literary website called Three Percent, Open Letter searches for works and authors that are “extraordinary and influential”—works that the press hopes “will become the classics of tomorrow,” according to its website.

To that end, Open Letter received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts last year to help fund its International Voices project, which will result in the translation and publication of five works of literature from around the world.

Fosse, of course, has become a shining example. On Thursday, he ascended the pinnacle of literary recognition for “his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable,” according to the Swedish Academy.

One of the world’s most widely performed playwrights, Fosse’s immense oeuvre written in Nynorsk (a literary form of Norwegian, based on country dialects and constructed in the 19th century as a national-language alternative to Danish) spans a variety of genres—novels, poetry collections, children’s books and translations, short stories, and essays.

To date, Fosse has been translated into more than 50 languages and has won many of the world’s prestigious literary prizes. Unsurprisingly, for the past decade, he’d been considered a top contender for the Nobel Prize.

Post, too, had anticipated Fosse’s win for several years, describing his work as “more conservative in structure, centered on the humanism of the artist and the struggle to exist within an unjust or strange society,” which, he says, fits more “with the Nobel vibe” rather than being focused on the “current tropes of identity politics.”

Septology, made up of seven novels in three books, published all in a single volume, is arguably Fosse’s magnum opus. It tells the story of the aging painter Asle, a widower, who over the course of seven days tries to make sense of religion, identity, art, and family life, with strong autobiographical undercurrents, including a literary tribute to Fosse’s late first wife and his own work as a painter.

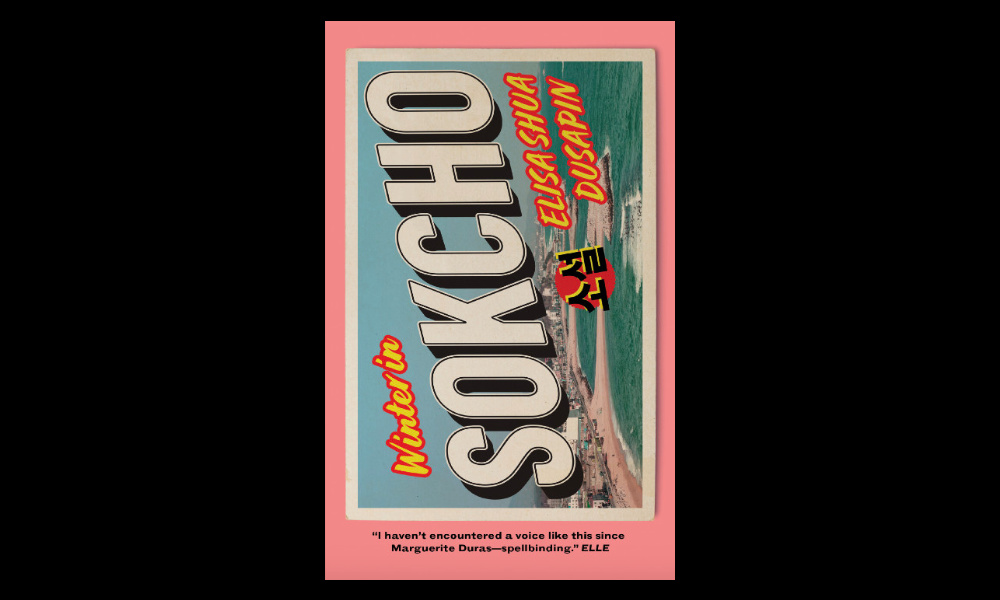

To first-time Fosse readers, Post recommends starting with Trilogy, which he says has a Samuel Beckett quality to it—“moving, very striking, and well-paced.”

“Fosse’s lyricism, his style, his focus on structure, and his heart is what makes him really an interesting and very cool writer to read,” says Post.

According to Post, more attention is paid to translated books today than a decade or two ago, yet the overall lack of focus on international writers across genres and countries persists, usually hovering around three percent of all titles published in the US.

“That’s just too few,” says Post.

Why does it matter?

“Without access to other cultures and other ways of looking at literature and life, and the representation of what life is through this artistic medium, we become isolated,” Post argues. It’s not just readers who suffer—American authors do, too, with fewer new influences and “fewer new ways of thinking or doing things.”

The University of Rochester, meanwhile, has a more than 30-year tradition of connecting readers with less accessible books and authors. Beyond Open Letter’s endeavors, Rochester houses the Middle English Text Series, a project that democratizes access to a wide range of medieval texts through free digital and affordable print editions.

Ultimately, providing a platform for global voices is especially important at a time of interwoven politics and economies, argues Post. “Being able to hear individual voices from remote parts of the world that you may never be able to visit, or people you may never encounter, adds to our overall understanding of the world at large.”