Alumnus Declan Spring ’87 and Open Letter’s Chad Post reflect on the vision and voice of the newly minted Nobel laureate.

Hungarian novelist, essayist, and screenwriter László Krasznahorkai has won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature for “his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art,” according to the Nobel committee. Calling him “a great epic writer in the Central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard,” the Swedish Academy, which awards the prize, describes his writings as marked by “absurdism and grotesque excess.”

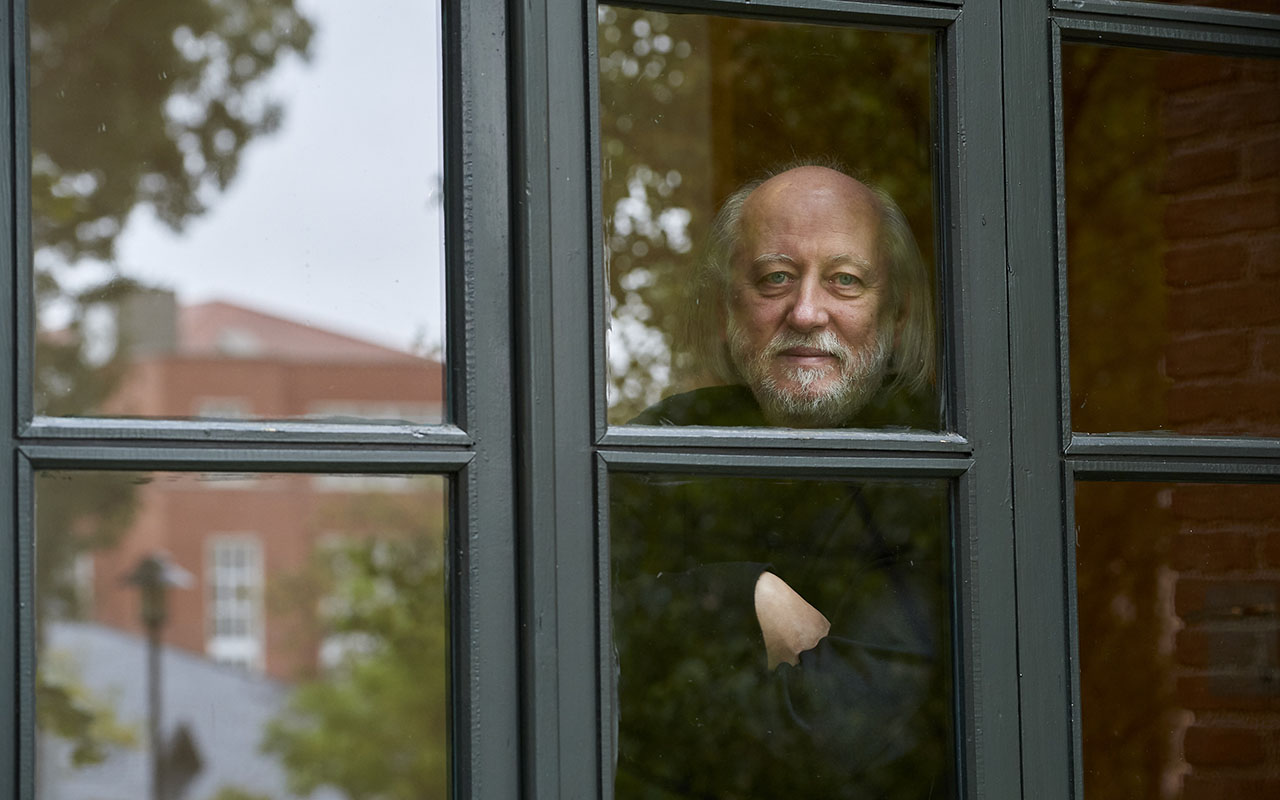

For University of Rochester alumnus Declan Spring ’87, the award was both thrilling and personal. Spring, executive vice president and senior editor at the legendary literary press New Directions, has edited Krasznahorkai in English for decades. “I knew he deserved it, but waking up this morning was just unbelievable,” says Spring. “I’ve gotten quite close to László and have worked on so many of his books. It was a very emotional experience.”

Spring first became aware of Krasznahorkai when the late American critic Susan Sontag recommended the Hungarian author to his press after having read the British edition of The Melancholy of Resistance. (Plus, it didn’t hurt that the New Directions team is close with the author’s German editor). From there, he and his colleagues recognized a voice that struck “a powerful chord with all of us,” recalls Spring.

Today, he says, the Nobel not only validates that vision but also provides crucial support for a lean publisher like New Directions that doesn’t publish commercial bestsellers: “We spent all morning frantically figuring out with our printers and distributor how quickly we could get the reprints out. Most of all, we’re happy for László.”

URochester’s literary translation ties

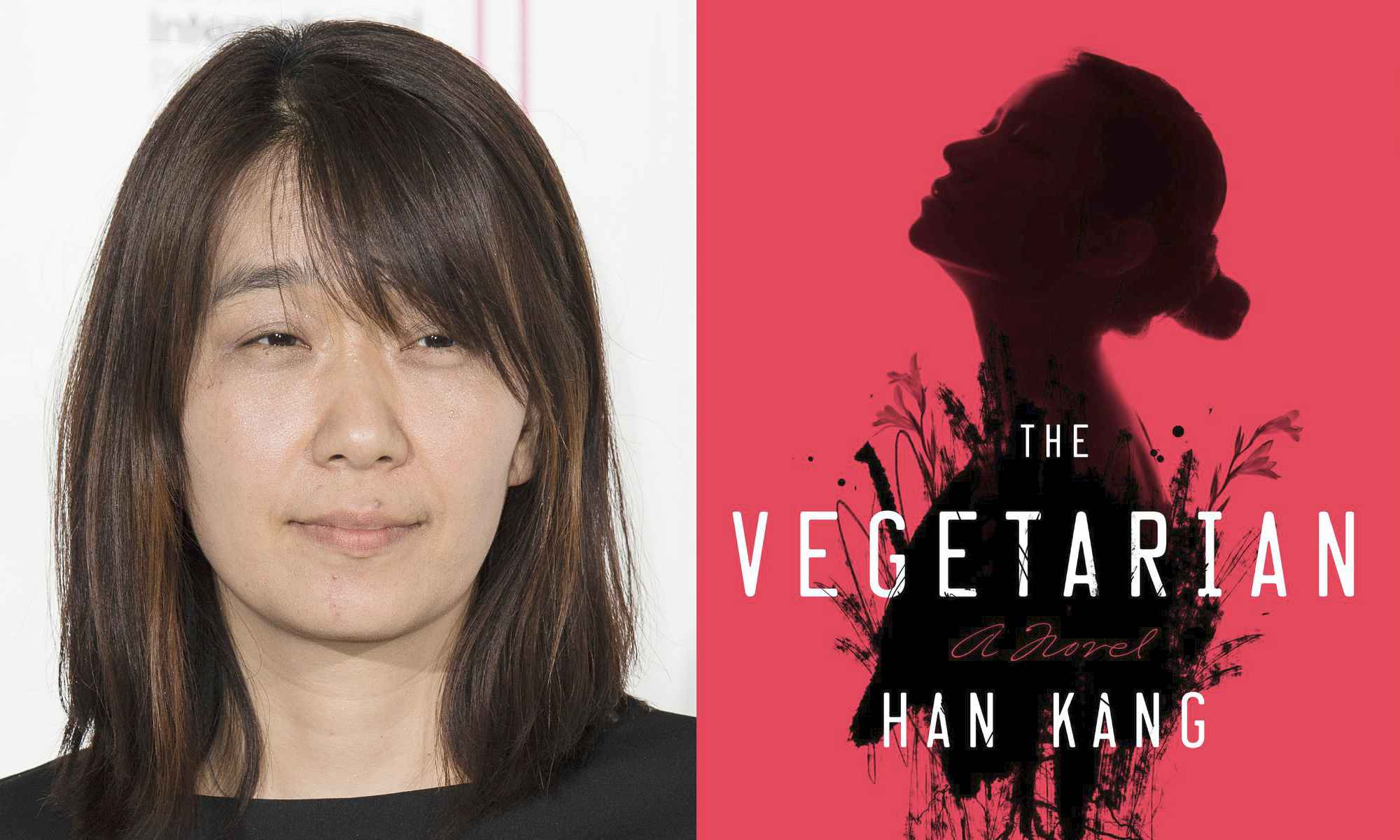

Spring isn’t the only URochester connection. Chad Post—who heads up Open Letter, the University’s nonprofit, literary translation press—has long admired Krasznahorkai’s work and has met the author. “It was only a matter of time until he won,” Post says.

Post helped award Krasznahorkai’s translated novels back-to-back Best Translated Book Awards in 2013 (Satantango) and again in 2014 (Seiobo There Below). The honor is administered by Three Percent, the online literary magazine of Open Letter that publishes essays and reviews, and hosts podcasts.

Although Open Letter hasn’t published Krasznahorkai’s work directly, its translators have connections to URochester. After all, it’s the work of translators, many of whom are authors themselves, that make books accessible to international audiences. Ottilie Mulzet (a pseudonym), who translated Seiobo There Below, spoke to Post’s graduate seminar on world literature and translation shortly after she won the Best Translated Book Award. The British poet and translator George Szirtes, another Krasznahorkai translator, had won the same award a year earlier.

Spring, who sits on Open Letter’s advisory board, has also returned to the URochester campus to speak to Post’s students about the art and craft of editing and publishing literary translations, and about his own formative experience at the University.

“I had the most brilliant and supportive professors,” among them English faculty members Bruce Johnson and Russ McDonald, says Spring. “They gave me so much confidence and got me even more excited about literature than I already was.”

Krasznahorkai’s singular style

Known for his dark and difficult novels, short stories, and essays, Krasznahorkai’s writing style is unmistakable.

Long, desultory sentences capture “the state of being for regular people, usually living with a sense that the apocalypse is just around the corner,” says Post.

Said apocalypse might come in the form of a Satan-like figure in his 1985 breakout debut novel Satantango, a strange circus in The Melancholy of Resistance, or the rise of neo-Nazis in Herscht 07769. His writing is driven by people rather than plot. As an example of his “looping, incredibly detailed sentences, which dazzle and overwhelm,” yet eschew a single period for more than 2,000 words, Post points to the opening of Herscht:

Angela Merkel, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Willy-Brandt-Straße 1, 10557 Berlin—that was the address he wrote down; then, in the upper left-hand corner, he wrote only Herscht 07769 and nothing else, signaling, as it were, the confidential nature of this matter; no point, he thought, in wasting words by adding any more precise indicators of his own self, as the post office would send the reply back to Kana based on the postcode, and here, in Kana, the post office could get the letter to him based on his name; most essentially, everything was contained on the piece of paper which he had just now folded twice, nicely and accurately, slipping it into the envelope, everything formulated in his own words that began by noting that the Chancellor, a learned natural scientist, would clearly and immediately understand what was on his mind here in Kana, Thuringia…

The challenge of his prose, however, offers abundant rewards to the patient reader. “His voice,” says Post, “is unique and instantly identifiable, rendered beautifully by his translators.”

Adds Spring, “He writes with such pathos about the human condition, his characters are so human and vulnerable. His writing style is poetic and elegant and he’s lucky to have a truly brilliant translator, Ottilie Mulzet.”

Krasznahorkai’s work has not only been translated on the page, but also to the big screen: Several of his novels have been adapted for film, most notably through his long collaboration with Hungarian director Béla Tarr.

For both Post and Spring, Krasznahorkai’s Nobel Prize shines an international light on the work of an author whose uncompromising vision has shaped their professional lives—and deepened URochester’s place in the global literary conversation.