Rochester Women

Sylvy Kornberg ’38, ’40M (MS)

Born: 1917, Rochester, New York

Died: 1986, San Mateo, California

A biochemist, Sylvy Kornberg ’38, ’40M (MS) made vital contributions to the research for which her husband, Arthur Kornberg ’41M (MD), won a Nobel Prize in 1959. As a full-time member of the research staff in her husband’s lab at Washington University in St. Louis, Kornberg “contributed significantly to the science surrounding the discovery of DNA polymerase,” Arthur Kornberg wrote in his 1989 autobiography, For the Love of Enzymes.

Rochester Women is a Newscenter series designed to share the stories of women in the University’s history whose contributions deserve wider recognition than they may have historically received.

During her career as a biochemist, Sylvy Kornberg ’38, ’40M (MS) was best known as the wife of Arthur Kornberg ’41M (MD), who won a Nobel Prize in medicine in 1959 for his role in the discovery of the mechanisms of DNA replication.

But as some of her colleagues knew at the time—including her husband—Sylvy Kornberg made vital contributions to the research for which Arthur won the Nobel. As Arthur wrote in his 1989 autobiography For the Love of Enzymes, “she had contributed significantly to the science surrounding the discovery of DNA polymerase,” the enzyme that sets the process of DNA replication in motion.

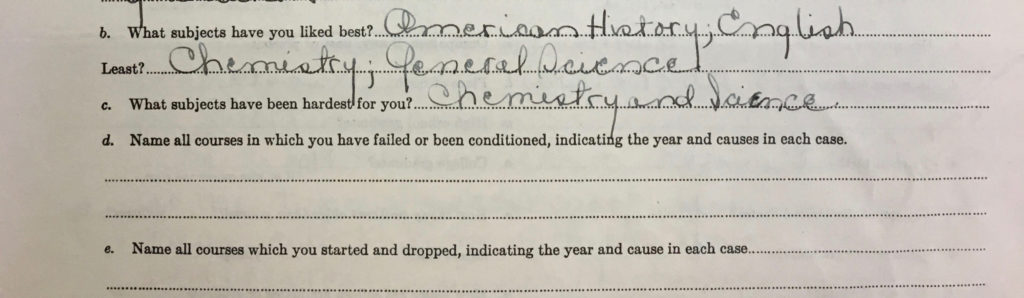

Born in Rochester as Sylvia Ruth Levy, Kornberg was raised in the city, where she was the daughter of Jewish parents who had fled Latvia and Belarus and never completed secondary school. When she applied to the University of Rochester, she reported her favorite subjects as American history and English, and to the question, “Which subjects have you liked least?,” she answered chemistry and general science. But in college, her interest in science grew, to the point where she was one of a handful of women students to commute from the College for Women’s campus on Prince Street to the College for Men—the River Campus—where the advanced courses in biology and chemistry were offered.

After earning her bachelor’s degree, she began graduate work in biochemistry at the School of Medicine and Dentistry under Walter Bloor, an expert on lipids. Her first job after completing her master’s degree was at the National Cancer Institute. There she became reacquainted with Arthur Kornberg, whom she had first met in Rochester, and who was by that time also at the National Institutes of Health. They married in 1943.

She took a multiyear break from the lab, during which she bore three sons—including Roger Kornberg, who would win the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2006. When Arthur accepted the position of chair of microbiology at Washington University in St. Louis in 1953, Sylvy resumed her research, completing the work that, in another age, might have earned her wide recognition.

That same year, James Watson and Francis Crick published their classic paper positing the double-helix structure of DNA. But how was the complex structure replicated? The Kornbergs, along with then postdoctoral fellows Robert Lehman and Maurice Bessman, and doctoral candidate Steven Zimmerman, delved into that question. As Lehman, now a professor emeritus at Stanford University, noted, the group was frustrated by failed attempts to generate a DNA replication. Sylvy Kornberg discovered an enzyme that degraded an essential triphosphate, clearing the path for successful replication.

She made other important contributions, including research on polyphosphates and their role in helping cells to store and retrieve energy. “The wide significance of this neglected area of energy metabolism is just now being appreciated,” Arthur Kornberg wrote in 1989.

But Sylvy Kornberg’s career was cut short when she was stricken with a rare neurodegenerative disease. The first symptoms of the disease, related to ALS, arose within a few years after the Kornbergs moved to Stanford University in 1959. Kornberg died of the illness in 1986.

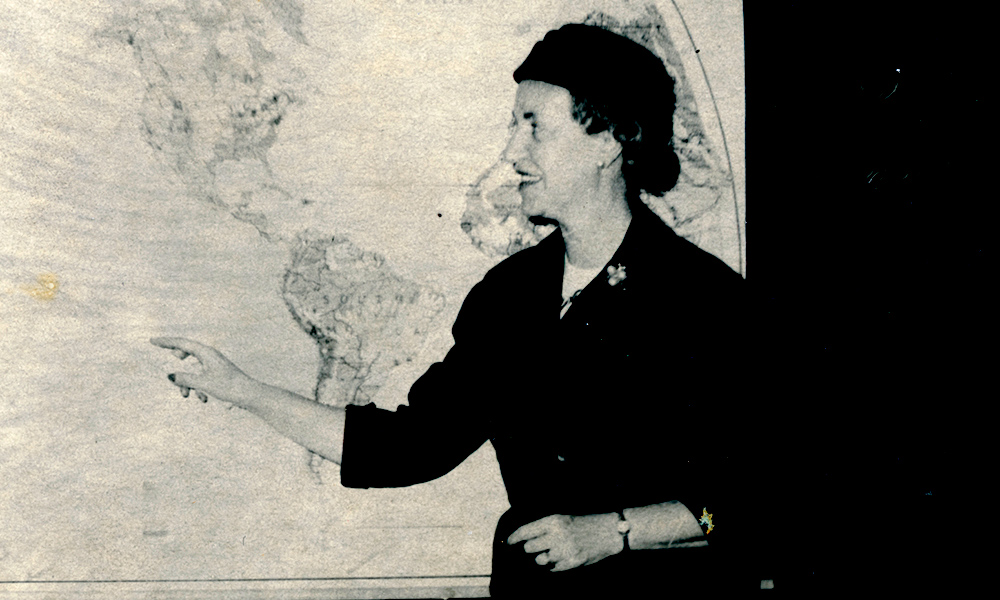

In spite of her achievements, Kornberg has remained an obscure figure in science. As recently as 2017, her image appeared in the Scientist magazine, where she was described as the “mystery woman” standing alongside chemist Jonathan Hartwell at the National Cancer Institute in the 1940s. When the institute was unable to identify the woman, the magazine turned to social media. The Kornbergs’ youngest son, Kenneth, an architect, replied, identifying the woman as his mother.

The Scientist followed up with an article devoted to Sylvy Kornberg’s life and work.

“[Her] deep interest in science, her enthusiasm, her work ethic, and all of that would, in today’s world, have led to a very different status and kind of career,” Roger Kornberg told the magazine.

Read more in Rochester Women

‘Your sexuality is yourself, as the total person you are’

The latest Rochester Women profile looks at the life of Mary Calderone ’39M (MD), a pioneering advocate for sex education who was both celebrated and vilified for her work during a time a great cultural division over sexuality and feminism.

‘This vacuum in our education is more than a matter of polite regret’

Vera Micheles Dean served as the founding director of the University’s Non-Western Civilizations program, one of the first such interdisciplinary programs for undergraduates in the country.

‘The memories of what happened to us then will never go away’

By the time of her death at age 103, Olivia Hooker ’62 (PhD) was an early witness to devastating acts of racist violence, the first African-American woman to serve in the Coast Guard, and a prominent psychology professor.