Rochester Women is a Newscenter series designed to share the stories of women in the University’s history whose contributions deserve wider recognition than they may have historically received.

Olivia Hooker ’62 (PhD) was in her 80s when she began some of the work for which she is best known. It was work she felt compelled to do after an extraordinary instance of racial violence, and the injustices that continues in its aftermath.

Newsmaker

Before Making Military History, She Witnessed One of History’s Worst Race Riots

In 2018, Olivia Hooker talked with NPR’s Story Corps project, a long-running series that becomes part of the National Archives.

Olivia J. Hooker ’62 (PhD)

Born: 1915, Muskogee, Oklahoma

Died: 2018, White Plains, New York

Olivia Hooker ’62 (PhD), a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, was a pathbreaker in multiple and disparate domains: a point person in efforts at restitution for victims of the Tulsa massacre; the first African-American woman to enlist and serve in active duty in the Coast Guard; and, after earning a PhD in psychology at a time when racial segregation, either legal or de facto, was ubiquitous in the United States, a valued teacher and mentor to her own students, and clinician who helped people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to reach their potentials.

“We did go on with our lives after the riot, but the memories of what happened to us then will never go away.”

—Testimony before the House Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties, April 2007

Hooker grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where her father owned a clothing store in a prosperous African-American neighborhood that was sometimes called “Black Wall Street.” In 1921, when Hooker was six years old, an accusation that a black man had assaulted a white woman led to an attack by a mob of white men on the neighborhood. Olivia hid under a dining room table with her siblings as rioters entered her home, destroying objects of value before moving on. The 24-hour assault led to the deaths of an estimated 300, mostly black, Tulsans and leveled more than 1,000 homes and black businesses—including the Hookers’ store.

“Nothing was left but rubble,” she told Rochester Review in 2005.

Victims received no compensation from their insurance companies, and no redress through the legal system. Indeed, as Hooker told a congressional subcommittee in 2007, few Americans knew of the violence at the time, because it was mainly—if not only—the black press that covered it.

In the late 1990s, she helped form the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, which made a case for reparations. While that goal has eluded the group, Hooker achieved one of her lifelong goals posthumously: a week after her death in 2018, the group, gearing up for the centennial anniversary of the tragedy, renamed itself the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission.

Following the massacre, Hooker’s family moved to Columbus, Ohio. As a college student at Ohio State University, Hooker became an activist in a campaign to secure for black women the same opportunities in the military that World War II was opening up for white women. She wanted to join the Navy, but her application was denied multiple times. Then, as she told the Coast Guard Compass blog in 2013, a friendly Coast Guard recruiter convinced her to join that branch instead, under its women’s reserve program, SPAR (“Semper Paratus, Always Ready”).

Hooker served from March 1945, when she reported to boot camp, to June 1946, when the SPAR program was disbanded. Her role, in Boston, consisted largely of paperwork. But “it taught me a lot about order and priorities,” she told the Compass.

In 2015, the Coast Guard named a dining center and a training facility in her honor.

Using GI benefits, Hooker enrolled at Teachers College, Columbia University, where she earned a master’s degree in psychological services. Following a stint working with female prisoners with developmental disabilities, she enrolled at the University of Rochester to earn her doctorate under the late Emory Cowen. Cowen had begun work on what became known as the Primary Mental Health Project—a pioneering example of community mental health. Hooker remained focused on people with developmental disabilities, exploring the learning capabilities of children with Down syndrome.

At Fordham University, where she taught from 1963 to 1985, she offered steadfast support as a mentor to students of color. “Following her ‘retirement,’ she was working harder than ever to ensure the field of psychology and federal, state, and local agencies were inclusive and working toward the benefit of all peoples,” Celia Fisher, the Marie Ward Doty University Chair in Ethics at Fordham, told Fordham News in 2018.

After her retirement from Fordham, Hooker spent 10 years as a psychologist at the Fred Keller School for Behavioral Analysis, a preschool that offers early intervention for children with developmental disabilities. She ended that job in 2002, at the age of 87.

Over the years, Hooker shared the ways in which memories of the massacre had left her traumatized. But in an interview with the Radio Diaries podcast in May 2018, she shared the advice her parents offered to her and her siblings. “Our parents told us, ‘Don’t spend your time agonizing over the past.’ They encouraged us to look forward and think about how you could make things better. I think things can get better. But,” she added wryly, “maybe it won’t be in a hurry.”

Read more in Rochester Women

‘Your sexuality is yourself, as the total person you are’

The latest Rochester Women profile looks at the life of Mary Calderone ’39M (MD), a pioneering advocate for sex education who was both celebrated and vilified for her work during a time a great cultural division over sexuality and feminism.

‘A very different status and kind of career’

The Rochester Women series continues with the story of Sylvy Kornberg ’38, ’40M (MS), a biochemist most often cited as the wife and the mother of Nobel Prize-winning scientists, but who played a critical role in the discovery of DNA replication.

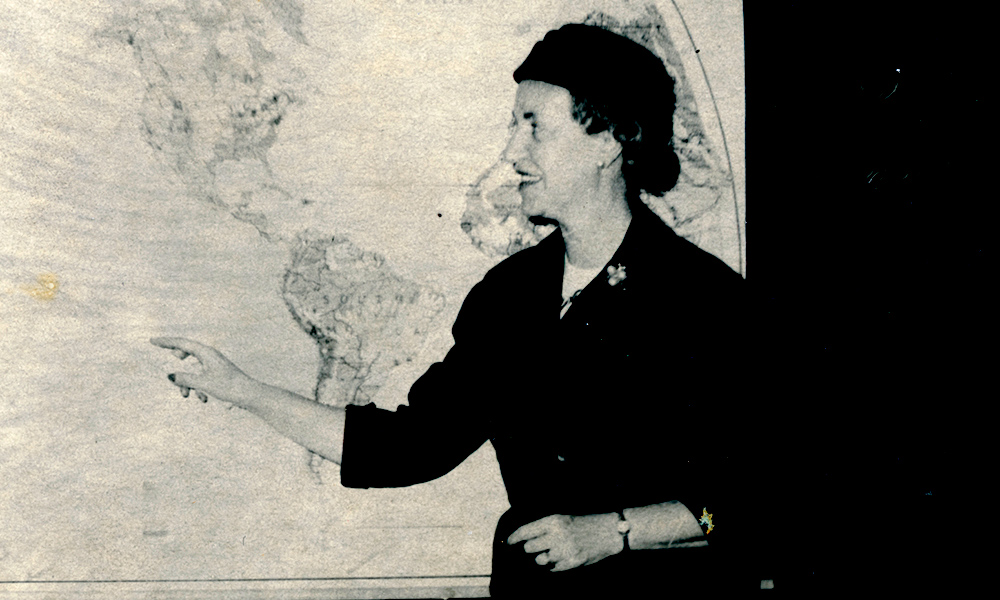

‘This vacuum in our education is more than a matter of polite regret’

Vera Micheles Dean served as the founding director of the University’s Non-Western Civilizations program, one of the first such interdisciplinary programs for undergraduates in the country.