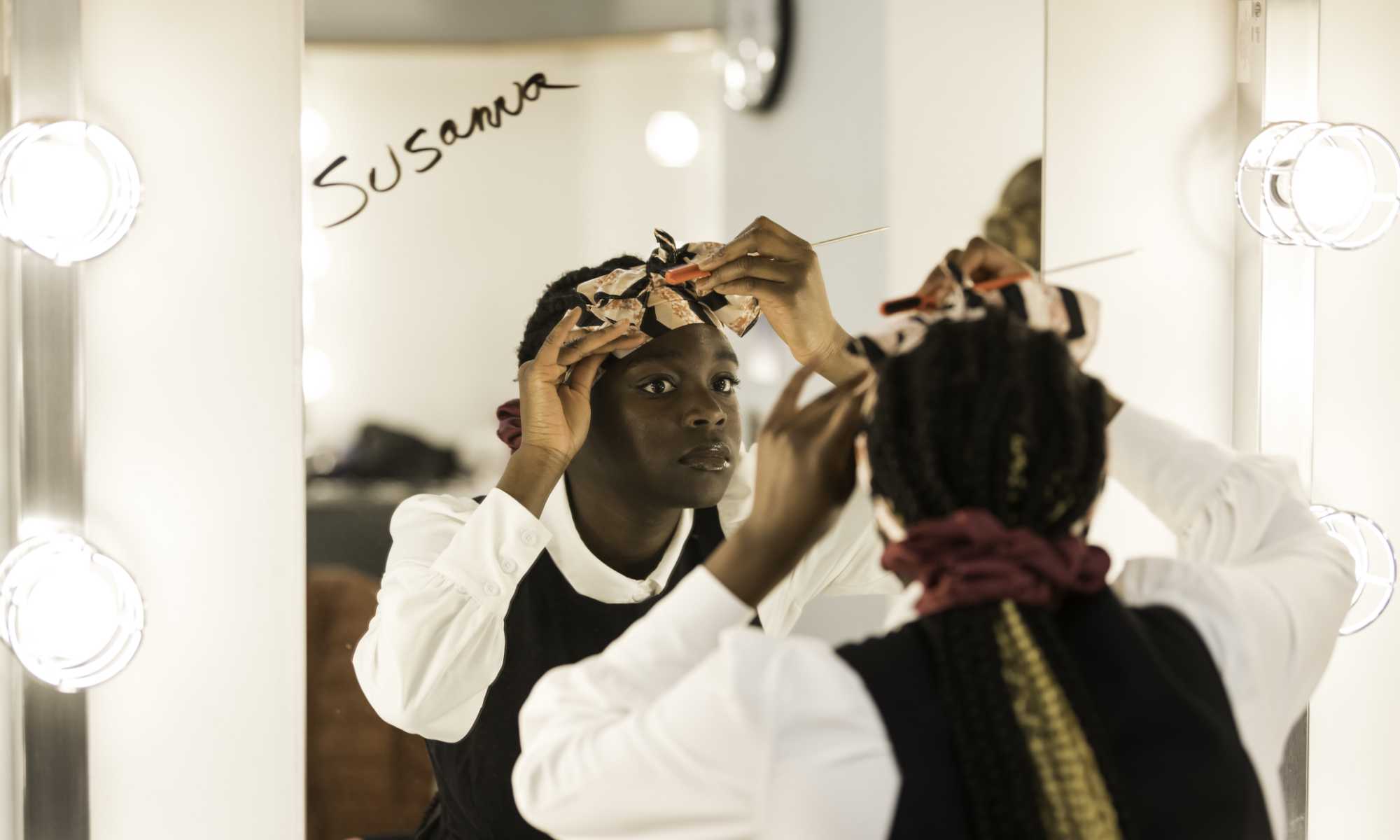

Fatoumatta Jobe is transcribing in Wolof—and then translating into English—centuries-old stories passed down orally.

University of Rochester student Fatoumatta Jobe ’23 has a story to tell. Dozens of stories, actually.

For the past year, the English and biology double major from The Gambia, Africa, has been using in-person interviews and WhatsApp to connect with around 30 elder members of her family and community, seeking stories that are centuries old and have been passed down like heirlooms.

“These are stories my grandmother was told by her grandmother, who was told by her grandmother, and so on,” she says. “Stories that only exist in the oral traditions of The Gambia and Senegal.”

Jobe audio records the interviews, then types up the stories in Wolof, the primary language of more than five million people in The Gambia, Senegal, and Mauritania. She plans to publish her Wolof transcriptions. But as her

senior research project for her English major, she is also translating the fables into English (also an official language of The Gambia).

As fables, the stories carry moral lessons. One is about a stubborn child who was warned against bothering birds. One day, he threw sticks at a bird until the bird turned on the boy and carried him around the forest until guiding him into a well. “That story is used to warn children against not listening to their mothers,” Jobe says.

Jobe’s father recently told her about a man whose family lived in poverty. He would sneak out for food and pretend to be hungry when he returned. A chicken told the family, and the man was so ashamed he turned into a hill. “So when you hear voices in the woods,” Jobe says, “know that an ashamed man is somewhere behind it.”

Jobe’s goal is to turn these conversations with elders in her country into an anthology of Gambian bedtime stories, preserving them for future generations.

Lucid retellings, says Professor Kenneth Gross

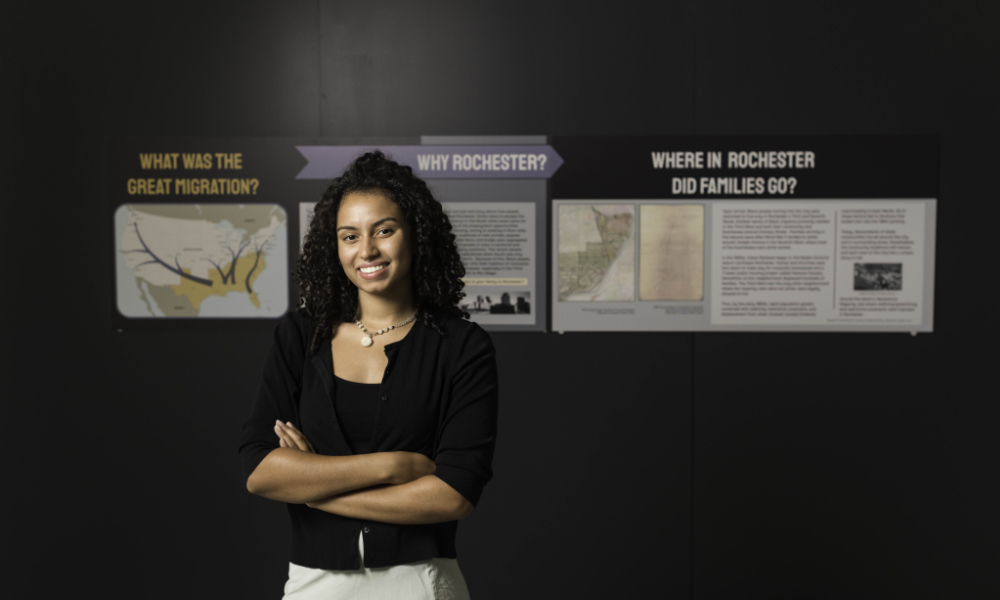

Jobe came to the University of Rochester after attending the African Leadership Academy, a selective college preparatory program in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“I did some online research and really loved that Rochester had an open curriculum, and I was able to explore different fields,” she says. “I came to Rochester sight unseen, but I love it.”

Since arriving on the River Campus, she has served as the former president of the Pan-African Students Association, a member of the Douglass Leadership House, and a Student Alumni Ambassador. She also works at the Simon Business School as a student engagement assistant.

The idea for the translation project came last year in a class called Dangerous Children taught by Kenneth Gross, the Alan F. Hilfiker Distinguished Professor of English. Says Gross: “I asked the students to share in writing some story that they had heard or read in childhood—to get them thinking about childhood, its imaginative world, and stories that belong to children.”

Jobe turned in what Gross calls “a vivid retelling” of a Gambian folktale, about a brave girl named Suntu and a magical ape who becomes human and helps her deal with her mean-spirited stepfamily.

“Her pages not only lucidly retold the story itself,” Gross says, “she also recalled the conditions under which she had heard it told repeatedly as a child by her father.”

Jobe wrote in her essay that her father would tuck her in every night at bedtime and tell her a story in Wolof until she fell asleep, or the story finished: “The story would always begin with my dad saying ‘Lëpp woon’ (a story of the past) and I would have to reply ‘Luppën’ (a story of today). My dad would then say ‘Amonafi’ (it happened once here), and I would reply ‘Däa na am’ (and it shall again). And then the story would start.”

Jobe’s final touch was providing Gross with a digital recording of her father singing in Wolof and translating the spell-like song at the center of the tale. “That spurred an interest in me to learn more about these stories that had been passed down for years and years,” Jobe says. “There are so many. They’re only being told orally, and people are dying. How would they be preserved for future generations?”

Her translation project started soon after. “I asked my dad a bunch of questions, and my grandmothers sent me stories on a group chat,” she says. “I reached out to an uncle who is an historian in The Gambia. A lot of it is word of mouth: who do you know that knows a lot of stories?”

Jobe did most of her interviews using WhatsApp, but she returned home over winter break after being awarded a research grant from the Department of English and the Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African-American Studies that helped cover her travel expenses. At home, she did in-person interviews. She has translated about 30 stories from Wolof into English. She intends to present the book for her honors thesis this semester—but also has bigger plans.

“Since embarking on this journey, I’ve been thinking about doing more research and producing various volumes that are more representative of various tribal groups in Gambia,” she says. “A friend of mine and I also have discussed making a documentary of the stories this summer so people can actually visualize them.”

Jobe has learned a lot about her country—and herself—during this process.

“I love talking to older people, especial Gambian people,” she says. “They know everything! I get to learn from them and laugh with them. My paternal grandmother loves that I’m doing this. And I’m learning that my creative capacity isn’t something of my own unique design. It’s literally within my culture to be creative.”

Jobe is applying to graduate schools but also keeping her career options open. “I’m interested in writing, but this experience has also taught me that I’m capable of doing research,” she says. “And I’m a STEM student, so I’ve learned that I can do that. But this research, this is where I flourish.”