The Very Pleasant Post

Usually I try and make the first post of the month one that’s based around some sort of statistical analysis of what’s going on with literature in translation. Since this is Women in Translation Month (#WIT2018), it would make a great deal of sense to run a bunch of data about women writers in translation, women translators, how many books written by women are translated by women and vice versa, which languages have the most parity (or don’t), which publishers have the best balance of male vs. female authors, etc., etc. And I will! . . . But not till the end of the month. I’m working hard to update the Translation Database (add your books if they’re missing!) and it would be foolish to run all the data before it’s as complete as it could be.

So we’ll save that.

In addition to providing a ton of data and analysis, my plan is to only write about books by women this month. (Ironically, I plan on writing about Knausgaard’s 9,000 page My Struggle: Volume 6 in September, which is so massively male.)

I also want to try and write a non-controversial, all rainbows and unicorns sort of post. For once. That seems pretty far outside of my snarky, cynical comfort zone, but who knows? It should be fun to write about things I really like. Let’s give it a try.

*

The Book of Riga edited by Eva Eglāja-Kristsone & Becca Parkinson, translated from the Latvian by Kaija Straumanis, Suzanne McQuade, Uldis Balodis, Ieva Lešinska, Mārta Ziemelis, Žanete Vēvere Pasqualini (Comma Press)

The article I was originally going to write was going to be called “Three Stories and Five Scams: A Primer in How Small Presses Survive.” But that’s a whole bunch of negativity! And every scam I’ve heard about in the past month—in relation to a few different small presses—really just boiled down to one thing: finding ways to not pay the people you’re supposed to. I mean, there are fun variations on this theme, like getting young translators to pay the press for their expertise and willingness to edit and publish a particular work. But still—so much negativity! And why crap on other small presses when there are so many more unsolvable problems just sitting there, begging for my anxiety’s attention?

Let’s start with a positive! I really dig this cover. Comma Press’s “City Series” has a nice look to it. It’s like a hipster architect vibe that I can totally get into. (See: Book of Havana, Book of Gaza.)

Unfortunately, the paper stock is just too white and the text too black. If you’re a reader’s reader you know exactly what I’m talking about. It’s not like a POD or vanity press style production, but it’s lacking those little touches that you find in commercially produced books. Penguin anthologies don’t have this sort of small-press feel to their pages. (And don’t tell me this isn’t important. We all judge books by their covers and their guts.) And don’t even get me started on the font inconsistencies—serif on the title page, which totally doesn’t match the sans serif headings preceding each of the stories:

That’s totally functional, but there’s just something . . . off. The spacing is too mechanical. It lacks a certain touch, a bit of care.

Whatever! Why are you nitpicking a font, you asshole? A book isn’t just an object, it’s a door!

On a coincidental upside, all three stories I want to talk about from here are written by women. My absolute favorite was “Where I Am” by Andra Neiburga, translated by Uldis Balodis. It’s the broadest, most continental of the stories included in the anthology, and one of the most complicated in terms of narrative.

Unfortunately, this is one of the last stories in the collection. Sequencing in short story collections—especially anthologies—is critical. Collections are like a restaurant—you have one, maybe two shots, to convince someone to stick with you for life. If your first experience isn’t great, it’s unlikely that you’ll come back for more. There are so many other options out there! (With better production standards. I mean, menu items and specialty cocktails.)

This collection—which is really one bleak-ass story after another, because apparently along with the Soviet Union, Latvia liberated itself from any sense of levity or joy—is totally misordered in my opinion. The first story is some sort of childish fable that involves a potential suicide (also referred to as “a Latvian clown”) who flies off to Lapland with a troll? What is that? From there, things get dark, overly serious, and fairly pedestrian until about halfway through the book.

Just like a restaurant always leads with it’s best dish, a baseball manger plays his best reliever at the moment with the highest leverage, and the most well-crafted stories lead off a collection. These are pretty much like the fundamental laws of thermodynamics, except, well, they’re capable of being violated . . .

“Wonderful New Latvia” by Ilze Jansone, translated by Suzanne McQuade is also very good. (Hi, Zan! BTW, your Reds bullpen is only 20th in MLB! With a positive WAR for the first time in three seasons! The future is bright! Especially once Matt Harvey is gone and Billy Hamilton’s wRC+ is higher than 67. 67?! Ooof.)

The weird thing about this story is that it’s basically a piece of propaganda for the still relatively new National Library in Riga. It’s about Katrina’s trip to her workplace (spoiler: it’s the library), during which she thinks about Riga, Latvia, the plans her cousin drew up for the library, who got to work there, etc.

The economy would grow (wages were paid by foreign businessmen, and were taxed according to the country where the worker came from—a new EU law. Those who stayed in Latvia got a tax break; if you weren’t stupid—and Katrina wasn’t—you wouldn’t pass that up), public transport would expand (with hardly any traffic jams, everyone would go about jovially, satisfied in their own contentedness), the job market would diversify (all sorts of new professions were being introduced by the Ministry of Welfare’s Employment Service that year alone), new goods would get made (consumer goods and cultural goods, don’t get too excited!), in short—the country would grow, and the Castle of Light was a perfectly justifiable talisman for such growth. Jeering and mocking didn’t matter, cynic would get themselves worked up in vain—even in Europe they’d notice how Latvia was blossoming. How could you not be proud to live in such a progressive country? Katrina looked on with pride as her workplace approached.

To be fair, the library—outside, inside, and in their restaurant—is pretty baller.

The other story I really liked was “Westside Garden” by Gundega Repše, translated by Kaija Straumanis. Whom I obviously know. Regardless of who translated it, this is one of the other actually well-developed stories in this anthology. No offense—a phrase that is meaningless when it comes to my weekly posts, I know, I know—but almost all of the other stories feel amateurish.

Which gives me ideas for a couple other research articles:

1) What percentage of anthologized authors ever get a standalone publication? Is there a standard? Granta‘s Spanish-language Novelist issue led to a ton (or a dozen?) authors getting a full-length book published, but what’s the rate for something like this? Or for Dalkey’s Best European Fiction (why not world fiction?) or Words Without Borders? It would be fun to try and calculate this and assign a future value to anthology inclusion.

2) How much more do translators from non-popular/trendy languages (meaning not French, not Spanish, not German, not Korean, not Japanese) have to do to get the same recognition and grants as those working from more “well-read” languages? I’m willing to bet—having done zero research—that there’s a donut effect. French/German/Spanish translators can get publications, media attention, and grants, as can translators of languages that are recognizably overlooked (Arabic), endangered, or otherwise “unique.” The middle of that chart—languages like Latvian, Estonian, Czech, Slovakian, Bengali—tend to fall into a sort of well. Not enough sales to land the translators on the “40 Translators to Watch!” lists (NB: This doesn’t exist, right?), get the sales to land the future jobs, or land the grants that make it a viable option to spend a significant portion of time bringing one of these literary cultures to the eyes and minds of English readers.

*

That last section isn’t very positive, Post.

Yeah, fair. A leopard can’t change all their spots all at once? But it’s not like I called anyone a crook or that their mission statement read like LeBron wrote it or anything.

Are you literally arguing for baby steps?

I suppose so. It seems to easy to go with the flow, but then I want to state my opinions, because that’s what makes life living and writing fun?

But why do you equate “opinions” with “being nasty”?

Is it really “nasty” or “negative” to say that a book’s interior could be improved? A critique—versus criticism, a concept Brian Wood talked to me about that I want to come back to in future weeks—is a pathway to being better. And that’s the goal of all of this, right? To make living better?

Sure, but you can do that through entertainment, not pointing out someone’s flaws.

Are we doing this thing again? The schizophrenic, two-sides-to-every-review thing?

You started it.

No, you did. Fuck this. I don’t want to talk about the role of opinions in criticism this week because that leads directly into Ben Moser’s review of This Little Art and the tidal wave of reactions that totally washed away the questions he posed.

Misogynist.

Wait, what? Am I calling myself a misogynist for wanting to talk about Ben’s review?

Pretty much. This is exactly why you’re not writing about it, right? You had a plan to talk about this controversy in relation to the unsatisfyingly non-public non-controversy surrounding Ma Bo’le’s Second Life and the way in which a translator imposed their art and wrote a bunch of the book. You were going to set up two sides—Moser questioning the “anything goes because we’re artists” line of contemporary translation theory-practice versus the war-like response to his posing of these questions in relation to a particularly beloved book on translation, with a second hinge that if these same virulent protestors were that invested in that particular idea, they really should be reading Goldblatt’s translation and championing it. But, in your mind, because you’re both narcissistic and paranoid, they’re ignoring the book you spent time and money and “your soul” on because all they care about is posturing. That’s misogynistic and, even if you dispute that, pretty fucked up at least.

So now we’re having interludes in which I shit on my own brain?

Your fault, buddy. Save it for next week, or a private conversation. Whatever. Keep on shining, you insane fool. Be seeing you.

*

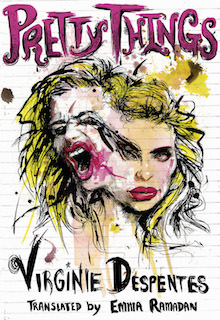

Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan (Feminist Press)

As of this moment, this is my Summer 2018 book. It’s culturally-philosophically spot fucking on, punk in numerous ways, compelling, unnerving, funny in ways, racy . . . Pretty Things has it all. The blurbs on the back—from Joanna Walsh, Lauren Elkin, and Alexandra Kleeman, all brilliant humans—are so perfect that I’m not sure what to add.

And of equal importance, I don’t want to *spoil* this book.

There’s a propulsiveness to Despentes’s books that’s easy to overlook in favor of the feminist edge of it all. (Joanna Walsh doesn’t overlook this in her blurb.) Her books are so exacting in terms of social power structures that it’s easy to talk about them in that way; at the same time, the novels of hers I’ve read (not a completist on this front yet, sorry) also have a really strong through-line that keeps you intrigued.

In this case, that through-line involves a twin who takes over her sister’s identity (when her sister kills herself) and gets sucked into the patriarchal-capitalist system—against her will, yet willingly—with the goal of becoming a media star.

I want you to experience the shifts of this book for yourself, but in brief, Pauline comes to Paris to pretend to be her twin sister Claudine—who resides at the “sluttier” end of that twin-spectrum, willing to sex club for promises of a a future record deal, because options in the patriarchal world are so fucked up—and ends up taking over Claudine’s name and persona.

As she gets sucked into this world of record executives (“Industry rule number four-thousand-and-eighty / Record company people are shady”) her autonomy gets dismantled in ways that will make you anxious, tearful, or enraged. All at once.

And as a reader you can’t see what will happen—will she be eaten up and destroyed? or figure out a way to screw over this AWFUL system and escape?—and that’s compelling as fuck.

Despentes isn’t Kathy Acker exactly, but she’s approaching the same problems in a different manner, and it’s super gratifying in a way that’s pulp and mentally stimulating.

My favorite part—the quote that’s my quote of 2018—is this bit when Pauline (now Claudine) is a famous singer/media-approved who decides to check out for a couple days and just play video games.

She plays Tomb Raider eventually—and ironically?—but right now she’s playing some Mario Cart-type thing with the one guy who was initially good to her, then had to go and want to bone her, because that’s the system and the system is horrible. Anyway, she’s playing a video game on a TV and a console (or whatever the correct lingo is):

He watches her play, tense over her controller. She does what girls do: scolds herself for things nonstop. “Fuck, Pauline, what are you doing,” instead of insulting the machine.

That! This! Whatever millennials say!

Nutshell!

It makes me want to cry. I read that and think of my daughter—or son, but let’s gender this for the final paragraph—blaming herself instead of the system.

Fuck the system. Fuck cynicism.

Leave a Reply