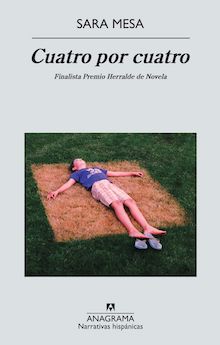

“Four by Four” by Sara Mesa

Below is an excerpt from Four by Four by Sara Mesa, translated by Katie Whittemore. To give you a bit of context, I’m including the synopsis that Katie sent us with her original sample:

The novel is composed of three sections, each written in a distinct narrative voice and style.

In Part One, we are introduced to Wybrany College, an isolated boarding school cut off from an increasingly chaotic, violent world in decay. Short, fragmented sections alternate between the first person narration of Celia, a fifteen year old “Special,” or scholarship student, and a third person omniscient voice who frequently narrates from the perspective of Ignacio, a younger boy of twelve.

Part Two takes the form of 56 diary entries written by Isidro Bedregare, a newly-arrived substitute teacher who is taking the place of the absent profesor García Medrano.

The epilogue, entitled “Heroes and Mercenaries: The Papers of García Medrano,” is composed, in effect, of García Medrano’s personal papers, which have come into the hands of the substitute Bedregare. Comprised of short sections—usually just several paragraphs long—depicting life in the “City,” García Medrano’s papers also reveal answers to the mysteries suggested in the elliptical first two parts of the novel.

In the original Spanish, the prose is marked by suggestion, insinuation, and a sense of unease, as well as allusions to some kind of event or shift in the outside world, a world like our own but existing in its own literary reality. The epilogue, in particular, feels allegorical or fable-like.

Mesa is engaged in literary world-building, too, as I should note that the city of Cárdenas appears in almost all the rest of Mesa’s work, including several of the stories in the collection Mala letra. And her first novel, An Invisible Fire, relates the last days of the city of Vado, which has become uninhabited and is referenced in the present novel.

Part One

Never More Than Two Hundred

CELIA

The contour of the landscape bends, yellows, and descends before dissolving in the distance. We are there, at the end, paused and panting under the motionless sky. It’s February and still cold. The air cuts off our breath, attacks Teeny’s lungs. She’s been sick for weeks.

We’ve never made it this far. Our sneakers are soaked from walking in the muddy grass, avoiding the roads.

We wait for Teeny to catch up and then convene a meeting.

“Should we eat breakfast now?” Valen asks.

Her chubby cheeks tremble. Valen is always hungry. The rest of us protest. It’s not time to eat. We’ve only stopped to decide where to continue on from here, from now. There is no time to waste; we’ll eat later, while we walk. Or we won’t eat at all.

We have two options: climb the hill until we reach the highway or follow the slope down and try to find the river. River is probably an exaggeration. Memory summons a groove, painted brown: a creek, at best. And memory doesn’t reveal its exact location, either. No one has been by here in years.

“I say we head for the highway. Then we can hitchhike wherever someone will take us.” Marina talks bravely but is chicken when it’s time for action. We’re not convinced.

I speak up. “Hitchhike? Are you crazy? They would bring us right back.”

“The river is safer,” Cristi says.

“But we don’t know where it is!” says Marina.

Cristi shrugs. Valen tries again, reaching for her backpack. “We could eat while we decide.”

“What do you think, Teeny?” I ask.

She looks up. Squints. The lenses of her glasses are fogged over. She coughs again. She coughs and blinks endlessly. Her nose runs. She’s full of fluid, Teeny is. I don’t even wait for her to respond. I speak for her: “Teeny doesn’t care what we do as long as we do it quick. Sitting around in this cold is going to kill her.”

“I think she should eat something,” Valen says.

“Shut up, you greasy fat ass,” Cristi says.

They fight. First, with insults. Then they throw themselves on the wet ground and roll around, theatrically, half-heartedly. Marina goads them. It’s not clear whose side she’s on. Teeny and I wait. She thinks about nothing and I try to think of everything.

It doesn’t matter. I see them coming in the 4×4, up the narrow, dusty path. They’re coming toward us and there we are, stopped, as stopped as time. A stirring of pride: thinking about being told off by the Booty or punished by the Head makes me feel better.

A quail chirps in the distance. Valen and Cristi get up, brush off their clothes, and look me in the eye. Neither one speaks, but I know they blame me.

IGNACIO

Wybrany College, seven in the evening. Ten or twelve boys in gym clothes hang around to see what’s happening. Silence has formed in the courtyard at the school’s entrance. Night is falling and Héctor walks escorted by his parents, the Head, and the Advisor. He walks by the boys. As he passes, he lifts his eyes and looks at Ignacio. At him, just him. The look is unmistakable, direct.

Ignacio shivers. The crunch of steps on the gravel lingers in his ears. He observes him from behind, the head of full, blonde hair, the smooth nape of his neck.

Only when he’s shaken roughly does he realize that they’ve been grumbling in his ear the whole time, and he hasn’t heard a thing.

“I’m talking to you, man, can’t you hear me?

Ignacio nods, craning his neck slightly toward the door through which the New Kid has disappeared.

The mother—or the woman he assumes is the mother—is outside, closing her umbrella. She has slender calves and iridescent stockings dotted with droplets of drizzle. Lux watches her, too, his head cocked and back arched, ready to flee at the slightest movement.

It’s November 1st. Ignacio’s birthday: twelve years old and finally the prospect of a friend to protect him.

“I said, what do you think of him?” the other boy insists.

“What do I know? I just saw him, is all.”

“But he looks queer, right?”

“Yeah, queer.”

Ignacio senses that the light is different, more yellow, or hazy. He can’t watch and listen at the same time, but they keep at him and their insistence has the echo of a command.

“Why queer?” the other boy presses.

“What do you mean, why? You said it.”

“Yeah, but why? Why did you say it, too? What do you know about that?”

A sad smile dawns on Ignacio’s face. Trapped again, he thinks, but what does it matter now that he will finally have a friend to protect him. The New Kid is tall, he’s strong, and out of all the faces on display there in the courtyard, he chose to look at him.

The girls’ laughter comes from the other side of the wall, a restless laughter, musical. He yearns for girls, but only as classmates.

“Because he laughs like a girl.”

“And you’ve heard him laugh, have you?”

“Before, when he arrived.”

“Before, where?”

He frees himself from the arm that grabs him.

“Before. Let me go, I have to go to class.”

“Class? What class? Classes are over.”

“Let me go,” he begs.

“Sissy, fag, fucking cripple,” the other boy says, releasing him.

Ignacio hobbles away, in his big shoe with the lift. Laughter screeches at his back.

Real or imagined, Ignacio hears it all the time.

HECTOR’S ORIGINS

But the New Kid’s origins go back to before, weeks before, days before; not that time matters much in this place, where the days so resemble one another. They accumulate, pile up, build on each other, creating an impression of continuity, of movement, or evolution of something.

It’s important to note, perhaps, that Héctor isn’t present on this occasion. Just the mother, or the woman that looks like the mother, and the father—him, for sure—in the Head’s office. They are joined by the assistant head of school, AKA the Booty.

The office doesn’t look like an office. It’s like a magnificent living room, with its crystal chandeliers and perfectly-worn Persian rugs—so vulgar, if too new—and gleaming floor-to-ceiling windows, the glass spotless, free of flies.

Seated in leather armchairs around a low table, they speak for a long time with the particular stiffness to which they are accustomed.

The Booty—who was, in another time, very beautiful—discreetly keeps her distance. Only when necessary does she add an opportune fact, blinking before she speaks. In general, such facts relate to fees, services, and requirements, the details of which the Head is ignorant, given that he delegates this minutia to her.

The tone of the conversation is sickly-sweet, good taste gone off a bit.

The office smells of cologne. Which cologne? Impossible to say. A mix of various scents: those worn by the people now present, and by all those who are absent, too. Those who sat where they are now, finalizing the details of their progeny’s matriculation.

The scent of the select, one could say, if it weren’t an oversimplification, because that’s not exactly how it is. Though one couldn’t claim the opposite, either.

“You realize we’re making an exception . . .”

“We know, we know,” Héctor’s father says.

He moves his hands, accentuating his words, like he did when he was a government minister. A rhetorical underscore, unnecessary.

“It will be more expensive—due to the exception, as you can imagine—still, you do insist?”

“Yes, we insist, we insist. It’s absolutely necessary.”

“Although it won’t be easy for us, getting rid of the boy,” the woman adds.

“Getting rid of isn’t the right expression,” he says. His eyes flash. He looks at his wife and she goes quiet.

The Booty smiles at them both. They shouldn’t feel uncomfortable, she says. Language betrays us all. Parents undeniably feel a sense of relief when they enroll their children at the college; it happens to everyone. Bringing up a child is a complicated act of responsibility that demands extreme dedication. There’s nothing wrong with leaving a piece of it in the hands of experts.

“Héctor is a brilliant boy,” the woman continues, speaking cautiously now. “Very intelligent, headstrong, a bit mischievous, maybe. He always finds a way to make his uniform a little bit different: a patch, a hole, a button pinned somewhere. As you know, he needs to do things his way.”

“Ah, but that’s good,” the Head says. “That’s very good. It speaks of character, strength of character, manliness. We don’t go overboard on rules here. Strict on the fundamentals, flexible on incidentals. Our educational methods are liberal, they’re based in absolute freedom. Will you have some . . .” He stares at Lux, who has just slipped through the bars on the window, “. . . coffee?”

They drink from little porcelain cups, served with biscuits that they barely nibble. Then they settle everything else: the registration, monthly payments, additional installments. The visitors express their surprise that rooms are shared, but nod sensibly at the explanation.

“Boys on their own, at this age, are hard to control,” says the Booty. “This way they keep an eye on each other. Spending their free time alone is not to their benefit.”

“Obviously some boarding schools make private rooms a mainstay of their appeal,” the Head continues, “precisely because they have nothing else to offer. Special menus, all the latest technology, professional sports facilities, blah, blah, blah . . . They’re only focused on the functional aspects of the issue. We guarantee a sufficient level of material comfort. Not excellent, perhaps, but sufficient. But we also guarantee an extraordinarily high-quality education, which goes far beyond academics. We do not impose discipline: the children impose it on themselves. Rigorous, not rigid. Firm, not harsh. Personalities are sculpted, polished until they shine. The country’s best have passed through here. We know how to shape the best.”

He carefully cleans his beard with a napkin and waits for a reaction. The couple smiles. They are notably, visibly relaxed.

An agreement has been reached.

Leave a Reply