Why Are Preview Lists [Galician Literature + Positivity]

I’ve been trying sooooooo hard to be positive in 2019. So hard. Stay optimistic in light of distribution issues. Don’t worry about sales too much, because I’m 250% certain Anthony is going to take us to the next level. Ignore the fact that Lit Hub listed Night School as one of the best reviewed “nonfiction” books of the week, because, who cares? At least we made the list.

And then, this.

I love that everyone at Open Letter tried to hide this list from me, since they knew I would lose my shit. And that I only found it because a friend emailed me with the subject “Trolling Globetrotters” and asked about my blood pressure re: all the Other Press books.

It’s . . . frustrating.

Look, I’m glad that it exists. Suburban couples deserve to hear about books from the rest of the world in addition to the latest Updike-esque knock-off. But, c’mon. Do some research. There are more than three presses doing translated books. Way more. The top publishers of literature in translation (AmazonCrossing, Dalkey Archive, Open Letter, Europa Editions) aren’t even on this.

Ugh.

Why do we bother publishing good books?

Why do I bother writing all these posts about books from truly underappreciated languages, countries, presses, and translators, when all the world wants is whatever’s the most obvious and safe.

This list is #FakeNews. Be better, or don’t bother.

Deep breath.

Wait, one more thing: Is it possible to create a more NY-centric list? (Sure, there’s one Transit book on there, but guess what, NY Times—there are presses doing international literature that AREN’T based in Brooklyn. SHOCKING I KNOW.) I mean, there IS A DATABASE DESIGNED TO RESEARCH THIS EXACT THING.

Also, I can’t stand anything that lazily reinforces the existing power base—whether we’re talking corporate policy or books. And this list does exactly that. Makes my skin crawl.

*

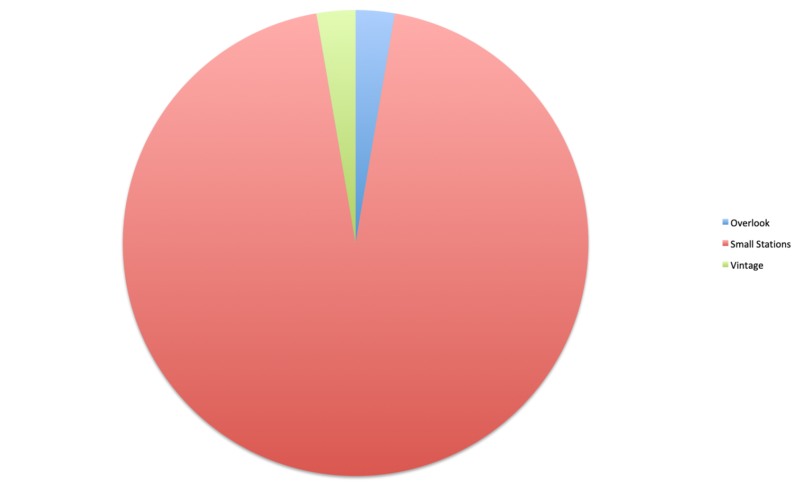

Now that that’s out, let’s talk about Galician, which is a distinct language, isn’t pronounced how you think it is, and is that northwestern part of Spain just above Portugal. (In case you were wondering.) Who publishes Galician books? Well.

That is 100% accurate. Small Stations for the win! They have literally cornered the market on Galician literature.

Which is why the rest of this post is basically just a list. I read a couple books by Suso de Toro in preparation for this post, so I’ll have a bit more to say about Polaroid and Tick-Tock, but working under the assumption that most people reading this haven’t read any Small Stations books (Polaroid was the first Galician book I’ve ever read), I’m just going to run down some highlights of their list. Also, check back in on Wednesday for a bonus Three Percent Podcast with Jonathan Dunne, founder and publisher of Small Stations, and one of the most prolific translators of Galician and Spanish.

*

Small Stations breaks their list up into four distinctive series: Galician Wave (YA titles), Galician Classics, Small Stations Fiction, and Small Stations Poetry.

Let’s start with the YA series, which is pretty unique. A year or so ago, Michael Reynolds from Europa Editions tweeted about how he wished there were more YA titles in translation for his children to read. I’ve never separated these out in the Translation Database (they’re all listed under fiction, which seems fine to me considering that the vast majority of casual readers read YA books), making it rather difficult to get accurate statistics, but anecdotally, I think he’s right. Every so often, a press decides to do kids books in translation (like Archipelago’s Elsewhere Editions), but you never really hear about anyone starting a line of YA novels.

Well, Small Stations has published fourteen titles in their YA series, which is pretty impressive.

One of their more recent additions is Europe Express by Andrea Maceiras, which is translated from the Galician by Jonathan Dunne.

“Nico is a computer programmer from Coruña in Galicia. On a business trip to the city of Bergen in Norway, he visits the quays of Bryggen, a place he has been to before. He buys a couple of postcards from a shop there and, much to his surprise, discovers that one of them has captured the moment when he and his friends visited Bergen on an Interrail trip after leaving school ten years earlier. There they all are: Óscar in his Deportivo football shirt with Bea; Nico with the slightly pretentious Mía, poring over a map; the Italian exchange student, Piero, a few feet behind them. But where is Nico’s girlfriend, Aroa, and his best friend from school, Xacobe, the other two members of the group? Nico is shocked to find that they are in a corner of the postcard away from the others and are kissing. He resolves to unearth all the mystery surrounding that trip and the bitter month of September that immediately followed, when a tragedy occurred, a tragedy that split the group apart and from which no one has recovered. He will invite all his friends to a school reunion and, by gauging their reactions to the postcard, finally learn the truth of what happened.”

There’s also a fantasy series by Elena Gallego Abad featuring a dragon, and a trilogy by Rosa Aneiros about a young woman named Leo who travels throughout Spain and Europe after graduating from college.

The classics list includes both fiction and poetry, including the works of Lois Pereiro and Rosalía de Castro. The title that caught my eye is Folks from Here and There by Álvaro Cunqueiro, partially because the description sounds pretty interesting, but also because part of this collection (Merlin and Company) was previously translated and published by Everyman. Even so, the only review I could find online about Cunqueiro was this one, which is from the quarterly journal published by the International Arthurian Society . . .

The classics list includes both fiction and poetry, including the works of Lois Pereiro and Rosalía de Castro. The title that caught my eye is Folks from Here and There by Álvaro Cunqueiro, partially because the description sounds pretty interesting, but also because part of this collection (Merlin and Company) was previously translated and published by Everyman. Even so, the only review I could find online about Cunqueiro was this one, which is from the quarterly journal published by the International Arthurian Society . . .

There are only four books in the poetry series, although one of these is by Manuel Rivas, the one Galician author who has made somewhat of a name for himself among English readers. Although The Carpenter’s Pencil is probably his best known book (in part because of the movie), Books Burn Badly has been on my radar for years. Jonathan gave me a copy years ago when I was in Bulgaria, and I remember reading a good chunk of it. (However, I don’t think I made it through all 550 pages . . . ) It’s the sort of book that I’d love to make time to go back to, especially in light of this glowing review by star translator Amanda Hopkinson.

Anyway, From Unknown to Unknown collects 80 of his poems, and is one of three Rivas books Small Stations has published in English translation. (They’ve also done a few of his books translated into Bulgarian.)

Anyway, From Unknown to Unknown collects 80 of his poems, and is one of three Rivas books Small Stations has published in English translation. (They’ve also done a few of his books translated into Bulgarian.)

Of the fiction titles they’ve done by him, The Potato Eaters sounds up my alley:

“Sam is a drug addict with a sense of humour. One particular escapade lands him in hospital, where he makes friends with the old man in the adjoining bed and becomes progressively enamoured of the nurse Miss Cowbutt’s unsung qualities.”

Finally, in terms of the fiction list, Jonathan recommended a few titles to me: Soundcheck by Miguel-Anxo Murado, Vicious by Xurxo Borrazás, An Animal Called Mist by Ledicia Costas (winner of the Spanish Book Award), and When There’s a Knock on the Door at Night by Xabier P. DoCampo.

All of these sounded really interesting—almost makes me want to do a whole month of Galician books just to get a better sense of their literary history—but the tagline at the top of the copy for Tick-Tock (“possibly the most impressive novel ever written in the Galician language”) was what turned me on to Suso de Toro.

All of these sounded really interesting—almost makes me want to do a whole month of Galician books just to get a better sense of their literary history—but the tagline at the top of the copy for Tick-Tock (“possibly the most impressive novel ever written in the Galician language”) was what turned me on to Suso de Toro.

Given how few Galician books I’ve read, I have no way of judging that statement, but man, these books (Tick-Tock and Polaroid) are wild. Supposedly they’re connected (Tick-Tock is referred to as a “sequel” in the jacket copy), although I’m not sure that matters. Both share a particular style and structure, somewhere between a set of interconnected stories and a novel, and there are a few names that resurface in both books, but you could honestly read one without the other and be perfectly fine.

Of the two, Tick-Tock definitely has more of a novelistic feel, with each of its five sections opening with a longer piece from Nano about his thoughts on life, history, aging, masturbation, etc., etc. Following those sort of framing pieces comes a series of much shorter anecdotes, mini-stories, musings from a philosopher’s many books (like On Getting Through Life, or Concerto for the Left Hand), little language games (like a section called “Aaah” that’s mostly onomatopoeia), or jokes (like the one about the Englishman, Dutchman, and Galician who argue about who has the biggest head).

These are really anarchic books, vacillating wildly from more violent, disturbed pieces (like the one in Polaroid about the blind man who beats his wife with his walking stick until she decides to poison him and his dog) to funny, voice-driven sections.

Here’s an excerpt that not only gives you a sense of Nano’s voice, but is a meta-reflection on the book itself:

No, writing isn’t just anything. It’s not as easy as people think. That’s why I haven’t plucked up the courage to publish everything I’ve written in a book. One day, I may pluck up the courage, if I get a bit of money together, if I win the lottery or something like that, then I’ll go to the printer’s and say, ‘Make me a book.’ The title I’d give it would be Hitting Hard because, if I ever brought out a book, then I’d say everything there is to say about life. Or else I’d call it Autopsy, which is what they do to you when you die in an accident or unfortunate circumstance. In an autopsy, they open you up and look inside and so find out everything about you scientifically. Well, not exactly everything, but almost. So in my book I’d say everything there is to say, as if it were an autopsy. Life as it is. Exactly as it is. A chaotic, nonsensical hodgepodge of voices and things, and I’d use the opportunity to include everything I’ve written in the book. Also, everything I’ve ever cut out, you see, whenever I come across a story I like in a book or article, well, I go and cut it out and keep it. So I’d put those things in as well. Photos even. I used to like to paint but, now I’m missing a hand, well, I sometimes hook up with a friend of mine who’s a photographer and we take some photos. I might even call it Tick-Tock, now that’s a real bummer, the passage of time. That’s the number one bummer. Or else I’d call it Cry, Baby, Cry, because of all that business with children.

It’s not immediately apparent in the above passage, but The Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov kept coming to mind as I read these. There’s a loose similarity in the way the books are structured, and there are even a few minotaur stories in Polaroid. So if you like Gospodinov’s novel, you might want to check these out.

*

Anyway, visit the Small Stations website and give one of their books a chance. It’s presses like these that are expanding the range of voices and cultures we have access to, and it’s a shame that they don’t get more attention.

I’ll be back next week with the final Spanish post of the month: All about Basque literature.

Leave a Reply