Biblioasis [Catherine Leroux Redux]

Last December, when I was working on this post about Quebec fiction, I came up with the idea of having themed months running throughout 2019. Which is why January was all about Spain, February about Quebec, and March about Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries. (Which might kill me and/or lead me into an insane rabbit-hole of increasingly esoteric posts about my mental state while reading such a gigantic book.)

Anyway, once I had this idea for structuring my weekly posts, I immediately wanted to schedule a month for Canadian publishers. Partially because I like a lot of them—and they get next to no play in the U.S.—but mainly because I wanted an excuse to read Catherine Leroux’s The Party Wall, translated from the French by Lazer Lederhendler and published by Biblioasis. And thank god I did. Over the past two months, she’s become one of my favorite contemporary writers. And I curse myself for not having read these books earlier . . .

*

Similar to what I did last week for QC Fiction, I want to highlight all of the Quebec titles that Biblioasis has published as part of their “International Translation Series.” (Which, you should all know, contains a number of non-Quebec authors as well. Definitely worth checking out!) But, because I’m struggling through some insane anxiety right now (I have a new computer, which is glorious, but we’re having trouble accessing the 1/18/2019 backup that contains literally everything that I need, which is . . . breathe, breathe, deep breath), I’m not sure how many smart things I’m going to say. Instead, I’m probably going to rely on Biblioasis’s descriptions and random thoughts . . .

I definitely want to start with The Party Wall though, about which, I do have some thoughts. First off: GO BUY THIS BOOK AND Madame Victoria. I really should’ve read this back in 2016 when it was first published in English—and was a Indies Introduce selection—or, if not then, at least last spring before I went and met Catherine Leroux as part of a special event at the Toronto Public Library celebrating the special Granta issue on Canadian writing. (Which was co-edited by Leroux and Madeleine Thien.) Then again, maybe I was meant to wait until now, because reading this over the past three days has been as gratifying as any literary experience I’ve had over the past couple years.

The Party Wall is the sort of book that I don’t want to spoil, which would absolutely happen if I went into too much detail about why exactly I like it . . . But here goes: This novel is made up of four different stories, each featuring a pair of characters. “Madeleine and Madeleine” is about a woman who finds out that she’s a chimera, containing two distinct sets of DNA, as if she basically encompassed her twin while in utero. “Ariel and Marie” features a very charismatic Canadian politician whose life is utterly derailed by information about his birth mother. “Simon and Carmen” revolves around the death of their mother and secret revelations about their father.

Each of those storylines appear twice in the book, whereas the fourth, “Monette and Angie,” occurs between every other chapter (seven times in total) and tells the story of two girls in Savannah, Georgia who walk to a grocery store to get candy.

So far, I’m sure this sounds like a rather conventional, if not a bit disjointed, novel. Which is pretty accurate. Each of these sections is utterly captivating, building its own particular world and conflicts, fleshing out its characters and raising the stakes over and over in a way that would make most conventional novelists really jealous. The theme of identity and one’s ancestors ties all of these pieces together, and, to be honest, the book would work pretty well if that were its only unifying structure. Instead, Leroux takes things to a masterful new level, linking together all of these stories in ways that are tricky to delineate, are generally unexpected, and that reward close readers.

Again, I can’t go into too much more detail without somewhat ruining the mental thrill of uncovering the underlying structure to this novel. Which is exactly what I liked about Madame Victoria as well. I’m a sucker for interesting structures, for books with a sort of architecture. It’s one of the things I love about Thomas Pynchon and Richard Powers and William Faulkner, and that has me dreaming about Leroux’s next novel (which Biblioasis publisher Dan Wells told me a bit about already). I find these sort of books to be so much more gratifying than titles that play it safe and stick to a more straightforward, easy-to-follow approach. (A statement that will surprise exactly no one.)

Again, I can’t go into too much more detail without somewhat ruining the mental thrill of uncovering the underlying structure to this novel. Which is exactly what I liked about Madame Victoria as well. I’m a sucker for interesting structures, for books with a sort of architecture. It’s one of the things I love about Thomas Pynchon and Richard Powers and William Faulkner, and that has me dreaming about Leroux’s next novel (which Biblioasis publisher Dan Wells told me a bit about already). I find these sort of books to be so much more gratifying than titles that play it safe and stick to a more straightforward, easy-to-follow approach. (A statement that will surprise exactly no one.)

It’s tricky to pull out a single paragraph to share here, so instead, here’s a bit from an interview the ABA did with Leroux when they selected The Party Wall as an Indies Introduce book. (I can’t envision a better response to sell this book to me than this one.)

Valerie Welbourn: In The Party Wall, there are many stories, characters, and layers that eventually connect. Was it difficult keeping so many threads going in your head?

Catherine Leroux: It would have been impossible to manage in my head. I created different tools to help me keep track — timelines, character summaries, a diamond-shaped graph, and esoteric calculations involving ages, specific dates, world events, and the future. And I’m terrible at math.

There are nine other works of Quebec literature in the Biblioasis International Translation Series, including The Dishwasher by Stéphane Larue, translated from the French by Pablo Strauss, forthcoming in May of 2019. Here’s the jacket copy:

It’s winter in Montreal, 2002, when a graphic design student’s gambling addiction starts to drag him under. In debt to the metal band that’s commissioned him to draw their album cover and ensnared in lies to his friends and his cousin, he takes the first job that promises a paycheck: dishwasher at La Trattoria, a high-end restaurant, where he finds himself thrust, on his first night, into roiling world of characters. A magnificent, hyperrealist debut, with a soundtrack by Iron Maiden, The Dishwasher plunges us into a world in which—for better or for worse—everyone depends on each other.

Iron Maiden, eh? That’s a curious choice.

Although the vast majority of titles that Biblioasis publishes in the series are works of fiction, they have brought out two poetry collections, both by Robert Melançon: Montreal Before Spring, translated by Donald McGrath and For as Far as the Eye Can See, translated by Judith Cowen.

Although the vast majority of titles that Biblioasis publishes in the series are works of fiction, they have brought out two poetry collections, both by Robert Melançon: Montreal Before Spring, translated by Donald McGrath and For as Far as the Eye Can See, translated by Judith Cowen.

I don’t know much about poetry, and nothing about Melançon, but a cursory glance of his Wikipedia page points out that he won the Governor’s General Award on two occasions: in 1979 for French language poetry or drama, and in 1990 for English to French translation. There’s something really impressive about that . . .

If you’d like to check out Melançon’s poetry, Biblioasis posted three poems by him back some time ago. Here’s one of them:

A VOICE HEARD IN A DREAM, UPON AWAKENING“Your days will pass, one by one,words in a breathless sentence strungtogether without punctuation, your actions,those thoughts that come at such a cost,won’t follow you, but if they doit will be as perpetually vain regrets, littlewill it matter, very little, whether youbetray or remain faithful, because each willcome to you in turn, everything willbe lost as if you’d been dreaming, it’s likea dream, the disorder of an old man’s lifethat comes back at the end, you’ll descendinto lower depths you don’t suspect are there,you’ll be seized, at times, by an unfathomable joybefore the expanse that evening will open upwhere the streets run out; impassive, the worldwill continue on its course, flowersthat will fade in autumn will come, snowthat’ll melt like snow in the sun, each daywill bring with it the History you’ll throw outwith the newspaper, with your boredom, you’llhave friendships that you’ll lose, love you’ll seefalling away from you, that you’ll tryin vain to hold onto, everything will begiven to you, everything taken away,everything will come, everything pass awaylike this night I’ve pulled you from, now go.”

Arvida is a collection of stories named after a town named after the American industrialist Arthur Vining Davis, who underwrote its construction around an aluminum smelting plant over the course of an astonishing 135 days back in 1927. As a child born to this far-flung outpost in Saguenay, Quebec, Archibald’s world was a tapestry of tales of madness, misfits, domesticated bears, and a Yeti-like cougar prowling the woods. The fact that Arvida was quickly absorbed by a neighboring town and exists, in a sense, solely as a memory only reinforces Archibald’s fascination with the mythic dimension of these private and shared histories. As he observed in an interview with the Canadian press, “growing up in a place that is so remote it’s on the edge or outside history, you never have any history except for the stories you told each other.”

There are two kinds of spaces in the narrative world of Arvida: the vast, unknowable ones of the Canadian wilderness, and the claustrophobic, unknowable ones of the home.

Archibald excels in the latter, filling domestic spaces with the minor chords (and occasional bloodcurdling screech) of gothic horror. Yet for all the attic rattlings and mythical predators that abound in this narrative world, there is nothing more frightening than the interactions among its inhabitants, or their behavior when left to indulge in isolation. As Bryan Demchinsky observed in the Montreal Gazette, “there’s a dark, hard presence in the stories, sometimes wry, sometimes muted, but always lurking” . . . most menacingly, perhaps, among armchairs and embroidered tablecloths.

(P.T. Smith)

One interesting thing about Mauricio Segura, whose Black Alley, translated by Dawn M. Cornelio, came out in 2010, is that he’s originally from Chile. Which likely informs this book that’s about the Cote-de-Negre area of Montreal, home to a lot of immigrants, including “Marcelo, the sensitive son of Chilean refugees, and Cleo, a shy boy from Haiti, [who] find friendship on the track, winning a major relay race together.” This sounds like a really interesting multicultural novel—one that probably would get a ton more attention if it had been released today.

It’s nice that Biblioasis tends to do multiple titles by the authors they include in this series. That’s something a lot of small presses aspire to, but aren’t always willing/able to pull off. Ondjaki, Mia Couto, Mauricio Segura, Catherine Leroux, and Robert Melançon all have multiple titles on this list. Oscar, translated from the French by Donald Winkler is based on jazz pianist Oscar Peterson. So rather than come up with something interesting to say about this book, let’s just hear some music.

And yes, I had to choose the most BuzzFeed of all available videos. It’s one of the nine times I’ve pulled that trick this year.

One more from Mauricio Segura! Eucalyptus, translated from the French by Donald Winkler. Although it’s stuck here in the middle, this is the final book from the International Translation Series that I’m writing about. I made it! (Sort of. There’s a bonus section below all of this for the true fans who want their weekly dose of nonsense.)

That said, I don’t have it in me to write up anything about this book. I’m sure it’s interesting. Dan has great taste. (Which reminds me that one of the only files I’m currently able to access from my old computer is the shitty manuscript I wrote in Marfa and sent to Dan and thought I deleted forever. Of course that was immediately downloaded to my desktop, whereas I’m still trying to get access to the complete list of current subscribers. UGH. This is giving me an ulcer and my first heart attack. Technology hates me.)

What I’m stuck on, mentally, right now, is whether this is my favorite—or least favorite—cover from this set of titles. I don’t like the earliest covers in this series, and some (Boundary and Arvida) are a bit too muted, color-wise, for my taste . . . I think Madame Victoria is my favorite. It looks like the cover of an indie rock album by a band whose lead singer I would fall in love with at a show.

For worse, Boundary: The Last Summer by Andrée A. Michaud, translated from the French by Donald Winkler is testament to the U.S.’s general indifference to books from Canada . . . Here’s what Kirkus had to say about this book in their *starred* review:

Boundary, an Edenic summer destination for families both American and French-Canadian, is haunted by the story of a trapper named Pete Landry, whose obsession with a local woman ended in tragedy. Years later, in 1967, Landry’s legend lives on, and when two young women are savagely murdered, the vacationers fear that his ghost may still roam the woods and lakeshore. Chief Inspector Michaud, however, called in to investigate the crimes, knows that he is seeking flesh-and-blood evil. Can he and his officers uncover the truth before another girl dies? This is a novel about liminal spaces and liminal time: much of the action occurs in the evening and at night, and even the year in which it’s set bridges the innocence and tumult of the 1960s. [. . .] Spellbinding. This novel is no light read, and beneath its layers lies a vision profoundly rewarding, beautiful, and tragic.

Given this, how many other reviews would you expect to find among U.S. magazines, newspapers, websites? Well, the answer is three. Publishers Weekly, Complete Review, and World Literature Today. That’s a bummer. Maybe the book is just OK, but I get the feeling if it had come out from a U.S. nonprofit, there would’ve been more online love . . .

I know shockingly little about Larry Tremblay. I remember coming across his plays years and years ago, but he has four novels translated into English, including The Orange Grove, translated from the French by Sheila Fischman, and something called The Obese Christ. Which, based on the title alone, is up my alley.

And although we call all agree Wikipedia is Wikipedia, this is intriguing:

Many of his plays focus on characters confronting psychological trauma. In Le Déclic du destin, a character progressively loses body parts; in The Dragonfly of Chicoutimi, the central character recovers from aphasia only to learn that while recovering his ability to speak he has lost his native language; and in La Hache a university professor is driven insane by his obsession with ideological purity in literature.

I need to do a better job paying attention to drama in translation. And international authors in general. It’s easy to feel like you know a lot by knowing a bit more than most people; then you realize how large the World Republic of Letters really is. (Or could be.)

Also: Sheila Fischman. I’m certain I’ve mentioned this before, but she’s translated almost 150 Quebec novels over her career, and has been nominated fourteen times for the Governor General’s Award for Translation. (Although only won it once?! Is she the Susan Lucci of Quebec translation?)

I feel like someone should publish a book about Fischman’s life and works, but so far, the best I can find is this essay that she wrote for Biblioasis.

Some thirty years ago when I wrote my first translation there was none of this. The novel, with the oddly–to me at the time–bilingual title La Guerre, Yes Sir! was published by the then young House of Anansi, after the translation I had done as a personal exercise had made the rounds of a number of other houses. I wanted to kiss the feet of Dennis Lee and Dave Godfrey for recognizing that it was an important book. And they wanted to pay me! Two hundred and fifty dollars! I did not want to accept it, this was a small, newborn publisher after all, but I was talked into it and spent the money on a pale blue suede coat. The sixties still had a few years to go . . . [. . .]

And now, thirty-odd years later, I’ve translated something like 150 books, or 138, I haven’t counted recently the books that now fill two complete shelves, plus overflow. I’ve had the tremendous pleasure of introducing some of my favourite writers to a broader readership–the English-speaking world. In most cases I have been the one who approached a publisher–with Lise Bissonnette, Christiane Frenette, François Gravel, Gaétan Soucy and Élise Turcotte and in particular, of Jacques Poulin. In some cases the publisher was won over instantly, in other cases–such as Poulin–it took years of patient wheedling. This aspect of my work never seems like work because I consider what I am doing to be a logical extension of my enthusiasm for a book or a writer. [. . .]

Still, literary translation does not always enjoy a comfortable seat at the literary table. This is due partly to ignorance of just what it is that we do and how we do it, partly to a misguided notion that being obliged to read a work in translation betrays a reader’s ignorance, so that translation is perceived as something shameful, an activity to be hidden or camouflaged. How many times have you heard someone say apologetically that she has “only” read a book in translation? As if every reader must have a profound knowledge and understanding of all the written languages in the world . . . This is particularly true in Canada, for other reasons that are perhaps political or at least socio-political. Should all Canadians be bilingual in French and English? Who knows? Maybe.

Someone out there with talent and connections should write long-form profiles on Sheila Fischman and Drenka Willen. Make it happen.

BONUS SECTION

Fail Better by Mark Kingwell is not the best book about baseball out there, but if you like memoirs about the game, about being a fan, about why baseball is the best, then this book is definitely for you. (Also, Kingwell is smart as fuck.) Now let’s talk about me. Here are my questions for the 2019 baseball season:

- Who will have a higher WAR/Annual Salary—Machado or Harper? (I bet Machado, because I think Harper is good, lucky, inconsistent, and an average defender.)

- Will Goldschmidt lead the Cardinals to the playoffs and,

- if so, will he win the NL MVP? (Yes, those are the two least analytically-minded questions I could come up with.)

- In 2018, league-wide, there were more strikeouts (41,207) than hits (41,018)—will that gap (189) increase or decrease?

- DH for both leagues? YES YES YES PLEASE. I’LL MOLLY BLOOM ALL OVER THAT RULE CHANGE.

- Will Hunter Pence bat .320? (NO. Sorry not-sorry for that callback.)

- Given that bullpens are dumb and rarely track from one year to the next, which team will have the greatest improvement from 2018 to 2019? Will Andrew Miller (💖💖💖) be part of this bullpen?

- How many teams will employ an “opener” in the first month of the season? How many in September/October?

- Will the Cubs miss the postseason again? And if so, how much am I allowed to celebrate without being an asshole?

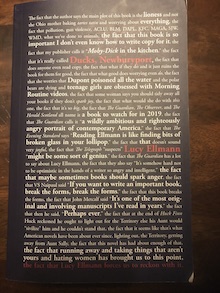

Read the “copy” to Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann. I want to assume Casey Plett wrote this (it’s not the same as the UK version) and I wish I could stop writing these posts long enough to read this 728-page book. So my jam. (I’m re-reading/reading Against the Day, which is a billion pages long, so hopefully I can make this my summer enjoyment read.) I would quote it here, but it’s one sentence, which is like Zone, but English and Man Booker eligible, so, advantage Ellmann, I hope you beat everyone and fuck I am way too anxious to let this post end.

Adding another Biblioasis recommendation to the list, this time from a Spanish language writer based in Montreal:”Red, Yellow, Green” (2017) by Bolivian-Canadian writer Alejandro Saravia, deftly translated by Maria Jose Gimenez.