The Five Tools, Part II: Translators [Let’s Praise More of My Friends]

. . . poor translations, he asserted, were the worst crimes an academic or a writer could commit, and a translator shouldn’t be allowed to call themselves a translator until their translation had been read by hundreds of scholars and for hundreds of years, so that, in short, a translator would never know if they were a successful translator in their lifetime, which, to Jacov, made perfect sense, and, following this train of thought, a translator wasn’t a real translator until they died . . .

—Reinhardt’s Garden, Mark Haber

There are a lot of great things to be said about Translation Loaf. The natural beauty of Vermont. The amazing instructors (which included John Balcom, Lissie Jaquette, Suzanne Jill Levine, Emily Wilson, and Edward Gauvin this time around). The summer camp vibe. All the readings—those by students and those by instructors. (Who didn’t fall in love with Helen MacDonald this year?)

Translation Bread Loaf

Those things alone make my visit to Translation Loaf one of my favorite weeks of the year, but looking back on it now, I think my absolute favorite thing is being able to talk to emerging (and experienced) translators in a number of different contexts. Some of my interactions are just basic, like my annual talk on contracts, while others are more situation-specific (giving advice to individual translators about their specific projects), and sometimes there are moments when I sort of think aloud and reflect on translation and publishing in a much more general way. This year that included giving really specific advice on how to write a good query letter and the “Three Levels of Translation.”

The query letter thing doesn’t really fit this post, so I’ll save it for later, but the Three Levels kind of does . . . To give you the full context, during my group meeting with ten translators, I started explaining to them why we chose to work with certain translators. Sure, it’s all relationships and coincidence, but there are reasons we keep working with particular translators that can be articulated.

This is painting with broad strokes, but translators tend to go through three stages:

1) Ability to translate words, literally

This is pretty basic, and where a lot of my students start out. They can render a sentence from one language to another and capture the meaning. This is what I think of as the “functional” stage of a translator’s career.

2) Ability to translate style

This includes the ability to capture tone and register, to understand how an author tells a story, to understand style and structure.

3) Ability to interpret and convey meta-patterns

Somewhat rare, but the greatest of translators understand the books they work on such a deep level that they know how to choose particular words to echo other parts of the text, to sequence subtle textual changes to illustrate the craft and structure of a book, and much more. This might seem similar to the earlier points, but there’s an intentionality and confidence among these translators that is palpable and alters one’s understanding of the text as a whole.

I’m more than willing to admit that this rubric is bullshit, but I have to be honest and admit that I do put translators into these three buckets and make certain decisions based on that. I want proposals from translators in stages 2 & 3 . . . But how do I know someone is at that level?

I have ideas! And these ideas dovetail with yesterday’s post about the Five Tools of Authorship: Are there “Five Tools of Translation”? If so, what are they? Are they different from the ones for authors?

I think the answer to all three of those rhetorical questions is “YES,” but before I explain, I need one more digression . . .

I just went through our catalog to try and identify all the translators whose first book-length translation we published (aka, Translation Debutants) ALONG with at least one more title. I’m probably missing a few people, but I came up with: Will Vanderhyden, J.T. Mahany, Steve Dolph, Lytton Smith, David Williams, maybe Heather Cleary . . . There are also quite a few translation debutants we’ve worked with, but have yet to do a second book with us. That isn’t a comment on their quality at all—in every instance I can think of, the translator is great but we haven’t found the right project yet—but for the purpose of this post I’m mostly thinking about the translators with multiple Open Letter projects.

What if we applied my “soccer player” idea to not just authors, but translators? Are there elements of translation that would cause me—as a publisher—to want to “buy” a translator’s future value early on? Like, if, you had bought Megan McDowell’s career—and published every author she’s worked on as part of that—it seems like you’d be doing really well.

It’s hard to divorce a translator’s qualities from the success of the book they’ve translated, but I’m going to give it my best shot. (Since, in a way, one of the qualities of a great translator is their ability to pick great projects. This is especially important for translators who are actively pitching projects.)

And just to make sure this is as clear as can be, I’m writing this from the point of view of a publisher looking to invest in translators. I’m not a professional (or amateur) translator and know that there are far more “tools” and aspects to the art and craft of translation than what I’ve listed below. This is my limited, flawed perspective, one that—once again—originates from the publishing/business side of things.

*

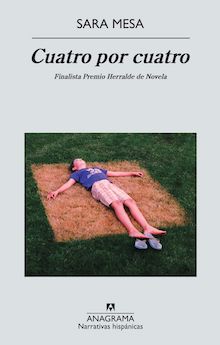

Before we get into the Five Tools of Translators, I want to shine a light on the most recent addition to the translators named above: Katie Whittemore. I met Whittemore at Bread Loaf last summer, where she read a short story from Sara Mesa—whose books are forthcoming from Open Letter, so, yes, this is full-on nepotism (or self-promotion or whatever)—and more or less started her career as a literary translator. Since last Translation Loaf, she’s published something like 49 stories and excerpts, and has seven full-length projects in the works with three different publishers. We’re planning on working with her on five different books, including Four by Four, which will be her debut . . .

Before we get into the Five Tools of Translators, I want to shine a light on the most recent addition to the translators named above: Katie Whittemore. I met Whittemore at Bread Loaf last summer, where she read a short story from Sara Mesa—whose books are forthcoming from Open Letter, so, yes, this is full-on nepotism (or self-promotion or whatever)—and more or less started her career as a literary translator. Since last Translation Loaf, she’s published something like 49 stories and excerpts, and has seven full-length projects in the works with three different publishers. We’re planning on working with her on five different books, including Four by Four, which will be her debut . . .

I could write this post with any of the above translators (or a hypothetical one) in mind, but given the recency of Bread Loaf and the fact that I got the first part of Sara Mesa’s Four by Four in over the weekend, it makes some sense to use Katie as a bit of a frame to help articulate what the Five Tools of Translation are—the tools that I’ll be looking for as I start working through this book.

Tool One: Tone and Register

I mentioned this above as part of the “second stage” of being a translator, but, to be honest, even within that second stage, some people are better at it than others. Some translators are attune to the nuances of tone and register, are very careful about choosing the right words for a particular character, about not jumping from an academic tone to a very informal one without rhyme or reason.

In terms of judging this as a “tool,” a really great translator will be more than consistent. More than accurate. A great translator is also a great writer, and a great writer (see yesterday’s post) uses atmosphere, tone, and register to create tension, expectation, and characterization. It’s one thing to do a functional translation that is internally consistent and “readable”; it’s another to produce a translation that captures the nuances of tone and register that make a book “fantastic.”

This is something that I’m not sure can be taught . . . It’s something that you can absorb by reading a lot, and having the ability to understand what the tone of the original is and how that tone can be conveyed in the target language. It requires the confidence to step away from the original a bit, which is one reason why beginning translators (who tend to be terrified about doing anything that’s not exactly like the original) struggle with this a lot. Usually when a translator says “that’s how it is in the original” they’re focusing on a solitary word choice rather than the overall tone/register/style of a piece.

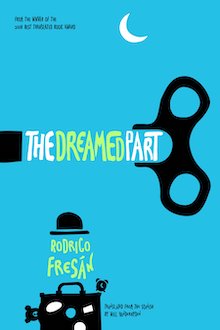

When a translator has a natural knack for capturing this (Will Vanderhyden is particularly gifted in this regard with his Fresán translations), they’re worth their weight in gold. It’s an incredible amount of work to transform a flat translation into something engaging. Which is why I would invest in a translator with this tool . . .

*

I’ll write more about the whole of Sara Mesa’s Four by Four in a few weeks, but for now, it’s worth noting that it’s comprised of three very different sections. The first is polyvocal, describing a boarding school in a possibly post-apocalyptic town that is attended by the elite and a handful of scholarship students. The second part is a diary from an aspiring writer who is working as a substitute in this school. The third is a surreal, unsettling journal from the teacher whom the substitute replaced.

These sections are very different and require shifts in tone and register to really work. Here are three paragraphs from Whittemore’s first draft that illustrate this:

Sara Mesa

THE SEAT

The new school year has just begun and her seat is empty. It’s been empty all week, almost since the first day, and the blank space is an accusation. Teeny knows that Celia isn’t sick, the others all know it too, but no one asks, no one says a word.

French class is about to start when the door opens and the Booty stalks in, asking permission as she makes her way through the rows of desks without waiting for an answer. She climbs up to the podium, smoothes her blouse, looks around, speaks.

She doesn’t talk about Celia, but she makes it known that absence is always the answer to something. She makes it clear, above all, that this absence is permanent.

She employs the usual symbols—caged birds, weeds that hinder the rosebushes’ nourishment, clouds that block the sun: a whole apparatus of lifeless nature she navigates naturally—but there is a tremor behind her words, an anxious fury, and this, yes, is strange.

The girls whisper among themselves, passing the words below their breath. A hum spreads like a net through the classroom.

From part II:

I met Señor J. and still don’t know what to make of him. The headmaster of the colich looks more like a stockholder than the head of a school. It’s hard to explain, but he looks like a smug businessman, not someone responsible for educating young people. A relaxed, self-satisfied man. Pleasant face, a deep, confident voice, a graying goatee that he strokes now and then.

He looks at me almost sweetly—ironically, perhaps—from behind his round glasses. He shakes my hand and welcomes me enthusiastically. Suddenly, I’m at ease.

The assistant head is also in the meeting. Skinny and pale with dark circles under his eyes, he’s submissive to Sr. J., eager to please. With him, there’s no firm handshake, just a limp and noncommittal grasp. He smiles broadly, showing long and yellowed teeth. He’s friendly, but it’s an awkward kind of friendliness: fixed gaze, stiff expression. I can’t say whether he liked me or not.

The conversation is short-lived. I have the impression that they both think I already know all the details about the school, or perhaps they don’t want to bore me early on with superfluous explanations. They limit themselves to brief, precise instructions. The assistant head gives me a folder with my students’ files, the notebook of the teacher I’m substituting for, a copy of my contract, and a memory stick.

“You start tomorrow,” he adds.

And finally:

THEY WERE TOLD IT WAS WORTH trying this way of life. It was a simple and easy life. They accepted. They forgot the old life.

Once in a while, a girl disappears, or a boy.

It became frequent and it became normal. And in becoming normal, it was accepted as the natural order of things. No one was overly sorry about it, just as no one is overly sorry about the fact that it sometimes rains or hails, given that—naturally—it has to rain and hail.

THE CONTRAST BETWEEN THEIR SKIN is pleasing. Between their bodies, ages. Occasionally, the contrast is grotesque, but always stimulating.

There are those who take pleasure in seeing this. The girl is thin, compliant; the man is flabby, covered in veins. A difference of forty years, perhaps more.

Symbols of power: the pants lowered and bunched over his shoes, the raised cigar in hand, an early sign of victory as he assails her over and over.

The girl doesn’t remember anything else and prefers this to loneliness.

She holds him when he’s finished, calls him papi. The one watching moves away, leaving them alone.

The watcher does not believe this coupling should be questioned. It is perfectly clear that it works.

One must never interfere with the laws of the market.

THERE IS A SINK, a toilet. The girl turns on the tap to watch one drop of water drip slowly, then another, and another. The falling droplets mark the time.

She moves closer. At first, it’s just a shiny quiver in the mouth of the faucet. It grows fuller and fatter, heavier, drops, and explodes.

One droplet. Then another.

Robinet, the girl whispers. She remembers that word from school.

She doesn’t remember “sink” or “toilet.” She doesn’t remember the school. She only remembers robinet, robinet.

There’s something sinister beneath all three excerpts, but it’s slightly different each time, which is something we’ll have to play with as we work on this translation. As it is though, the changes in rhythm—evolving from longer, more objective sentences to something more informal to a world that appears quite strange and disturbing—along with particular word choices make these bits work.

Tool Two: Ear and Fluidity

This is kind of close to tone/register, but I think it deserves its own category. If tone/register is the translation equivalent of baseball’s “hitting for power,” this is the one for “hitting for contact.” Both are about hitting, but different aspects of it.

A translator with this tool avoids those stilted bits of mediocre translations that turn off general readers. Although translationese can show up anywhere, a lot of times it can be found in dialogue. Awkward, unbelievable conversations can completely kill a book. I mentioned something similar yesterday about being “taken out of a book” when a voice doesn’t feel quite authentic—that fear is ten times more prominent when it comes to translations. Although I don’t believe that readers are genuinely “afraid” of translations, I do have the sense that the slightest stumble will remind them that they’re reading a translation, causing at least some portion of readers to set the book aside. We don’t want that!

Like with tone/register, the best way to develop a good ear is by reading a lot and writing a lot. Having a sense for how things sound in English and the confidence to step away from the original text to make sure that the text sounds right. Easier said than done, I know, but when a translator has this feel for language, their translations tend to read really well and, for better or worse, a translation that reads really well will be more “valuable” than one that has meaningful cultural content but is rendered in a stiff, awkward way.

Tool Three: Flexibility

After years and years of working with translations, I’ve become pretty good at identifying when a translator is sticking too close to the original rather than having the flexibility to know what can come over in the translation, and what needs to be left behind. I’ve heard a number of translators talk about compensation within a text—knowing that one pun/joke won’t work, but regaining that in a different spot by adding something that wasn’t there in the original.

That’s the sort of flexibility that sets a translator apart. It’s kind of like knowing your limits. Never trust a translator (or a writer) who thinks they can translate (or write) everything. I remember talking to Jordan Stump once about translating a book for Dalkey, and he passed because, although he loved the book, he knew that he would never be able to capture the voice in a satisfactory way.

Since I’m not a translator, I’m probably overstepping my bounds a bit, but I think that the idea of “flexibility” can encompass a number of different approaches to translation. Whether or not you take more of a Venuti approach and make sure the text proclaims its status as a translation through the inclusion of various “foreign” elements. And for someone trying to really domesticate a potential bestseller, they also need to have a certain flexibility in both thinking and writing.

I think there’s a lot more that could be said about this (or explained by a professional translator), but I’ll let it go for now.

Tool Four: Interpretation and Readership Strategy

This is key for me, both in terms of the translation itself AND in pitching a translation to a prospective publisher.

John Balcom

The idea for this came up during John Balcom’s talk in Bread Loaf last week. He compared a couple different translations of an epic, extremely important and extremely long, Chinese novel and articulated the ways in which the two different translations were aimed at different types of readership. One translation was done in such a way as to imitate a Victorian novel. People like Victorian novels, and the form did sort of map onto the original, so the translators used various Tom Jones tricks in rendering it in English. A more recent translation was done for a more general, contemporary readership, employing a much lower register, more slang, a certain looseness in the text.

Both versions have their pros and cons and, as anyone involved in this part of the literary world knows, there’s no single, right way to do a translation. My point: As much as a translator allows the source text to guide them, they still have to make a series of choices, and if they have some overarching idea of what’s best for the book—based on an interpretation and close reading of the original—their translation will work much better. Again, this is related to what I think of as a confident translation. The choices are deliberate and work together as a whole. Like when talking about style, it’s hard to put a finger on this, but when a translator has it, they have it. And I would totally invest in their career!

*

Related to that, and to bring Katie Whittemore back in here for a second, is the ability to present a title to a publisher in such a way that it’s clear that you, as a translator, understand what makes the book work. What makes it a good piece of writing.

I’m never swayed by reader’s reports (or cover letters) that rely exclusively on a book’s cultural importance as the reason why we simply must bring them into English. There’s more to publishing than simply doing a book because it’s worthy of being translated. That’s part of it, sure, but just as when agents talk about how many copies a book sold in its original country (🙄), I feel like we’re missing something essential. I greatly prefer reports and cover letters that articulate a way to approach the book. That unpack its style, its structure. That can explain why this particular book is better than the 70,000 other books we could be publishing. (And don’t tell me it’s because the book is important and has been overlooked. I want specifics! Specifics and urgency. Why this book. Why now.)

This is one of the key elements in why we’ve signed on a number of projects that Katie Whittemore has presented to us. Her reports provide a deep dive into the text itself, and knowing that she knows a) how a book works and b) how to talk about it, gives me a great deal of confidence that she’ll be able to do a good job with the translation. Or, at least, be able to explain her thinking in the editing process. And/or be able to take edits and work them through a more interpretive lens that’s informing the translation.

Translators with this tool are incredibly valuable. Especially if their aesthetics of reading are in line with your press’s . . . To have someone capable of both pitching the right books, and being able to translate them at such a sophisticated level is invaluable. Buy this translator’s career! $25K up front and $5K per title! (Or more.)

*

One last note on this: That “third stage” reference above fits in here, I think. There are lots and lots of readers in the world, but not nearly so many readers. Translators who understand how an author’s prose works on a line-by-line basis, and can see the structure of the book as a whole, and can pick up on textual patterns that run throughout the text echoing and playing off one another? Those translators are likely to have long, prosperous careers. (If prosperity and quality actually correlate, which is . . . not that likely?)

Tool Five: Cultural and Literary Fluency

One one level this seems really obvious: A good translator understands the cultural context a text is coming out of AND the cultural context into which they’re translating it. Is that really that simple and obvious though? There’s a tendency among emerging translators to either over-explain or under-explain cultural differences. Great translators know how to avoid footnotes, and have the flexibility to know what can be brought over wholesale, and what needs to be recontextualized.

Again, in the simplest terms, it’s the difference between knowing the language and knowing the culture surrounding the text being translated. This can also be extended into understanding the literary tradition a book is coming out of. A translator who knows what books/ideas their author is reacting to, or referencing, or playing with, is much more likely to produce a 10-star translation. (Or, in Norwegian parlance, a “6,” because, yes, they grade all books on a scale of 1 to 6 and then put a picture of a die with the appropriate number of dots on the front cover of the book, which is, in my opinion, a bit maddening because no one thinks in sixes. Just a little fun fact for anyone who’s made it this far.)

Again, in the simplest terms, it’s the difference between knowing the language and knowing the culture surrounding the text being translated. This can also be extended into understanding the literary tradition a book is coming out of. A translator who knows what books/ideas their author is reacting to, or referencing, or playing with, is much more likely to produce a 10-star translation. (Or, in Norwegian parlance, a “6,” because, yes, they grade all books on a scale of 1 to 6 and then put a picture of a die with the appropriate number of dots on the front cover of the book, which is, in my opinion, a bit maddening because no one thinks in sixes. Just a little fun fact for anyone who’s made it this far.)

The same level of literary fluency with regard to the target language is also necessary. In the end, maybe all these tools come down to being really well-read . . . If you know a lot about literature, you have more tools at your disposal to play with when you’re working on a text. You know where it’s coming from, what other works it’s in conversation with, and how you can capture those relations in both the English language and the American marketplace.

A great example of this is Will Vanderhyden’s translations of Rodrigo Fresán’s books. Rodrigo is a self-proclaimed “referential maniac,” who has read/seen/listened to so much. Granted, a lot of the movies and music he works into his texts are from America, but Will still has to know these allusions in order to make sure they land right in the translation. Because he’s read a lot of Philip K. Dick and Fresán’s other works and contemporary, weird Spanish-language literature as a whole, Will’s well-suited for making all of these references play.

*

One final thought about these “Tools”: Although the Five Tools I’d use to predict an author’s future are different from the five I use with translators, it’s not like one set is easier to attain than the other. Both sets of debutant writers have to be excellent at a lot of different things for a publisher to have a lot of confidence in their future output. Writing is hard! I know everyone thinks they can do it (and everyone can, technically write, I suppose), but you can easily tell the difference between a Five Tool Author or Translator and someone whose writing is totally fine (they roll a 3?).

More people need to read this and understand this side of the story. I can’t believe you’re not popular on the internet.