Is It Real? [A January 2020 Reading Diary with Charts & Observations]

It’s been sooooo long since I actually wrote something for here . . . I’m not entirely sure how to start! Chad 1.0 would open with something like “$%*# agents” and then go off on a couple individuals who are currently driving me INSANE. Chad 2.0 would come up with some wacky premise that blends ideas behind sabermetrics with distant reading in an attempt to think about a particular press, country, grouping of books in a unique way.

But what should Chad 3.0 write like?

(And yes, I know this versioning of my writing self is stupid. So stupid! But it’s kind of become a thing with my friends. Partially an honest attempt to become a better person, partially an attempt to figure out what might be interesting to the readers who come here.)

I spent a lot of time in December—particularly in Guadalajara, during the book fair—trying to figure out what the rubric for Three Percent would be in 2020. I couldn’t come up with anything that I believed in. I highly doubt anyone’s noticed this, but the past couple years have had very big themes behind them. The series of posts I wrote in 2018—that dove into the slough of despond and anger, intentionally and tongue-in-cheek so that I could create a narrative arc about value that unfolded over the course of the year—pretty much failed. And 2019 ended with a sputter . . . An interview with Charlie Coombe that I messed up and forgot about, and no original posts whatsoever in December.

When I was in Guadalajara, failing to find a new approach to writing about the appreciation of international literature and the business of books, I decided to double-down on writing only for myself. I have a vision of a book I want to put together that’s grounded in ten interviews with translators I’m doing as part of my spring class (starting Thursday with Lola Rogers talking about The Colonel’s Wife). I don’t want to go into too much detail, but in general, I want to try and write about the ways in which a translator’s role as interpreter can influence the way in which one relates to a work in translation. I’m planning on bringing in all my normal hobby horses, and weaving a sort of “reader’s narrative” through a series of interstitial bits implanted in the transcribed interviews.

Anyway, point being, I’ve been struggling with that all month and feel like I’ve sort of lost my way . . . This is one of the most clichéd things I’ll ever write, but writing these posts has been such a constant in my life for the past two, four, THIRTEEN (?!??!!) years, that I feel like I’ve lost a part of myself by not talking my bullshit every so often.

So, I decided to try something. Once a month I’m going to write some sort of “reader’s journal” that can take any number of forms, but will look at translation stats, books I read, underrated translations, publishing news, bad jokes, whatever. This is old school blogging—overly personal, rather unfocused, a space that’s as much about voice as it is content. Chad 3.0 is about embracing that chaos.

*

Let’s start with something that’s been troubling me—and taking up most all of my weekend hours—over the past few weeks: the State of Translations in 2019. I’ve been working on an article for Publishers Weekly about the decade in translation (caveat: I don’t believe in the decade ending on a “9 year.” The decade runs from 2011-2020, because you count from 1 to 10, not 0 to 9. But whatever. If LitHub believes the decade just ended, who am I to raise questions?) and had to put everything on pause to research, to dig into Ingram iPage and myriad small press catalogs to try and understand either a) what went wrong in 2019, or b) figure out what I missed.

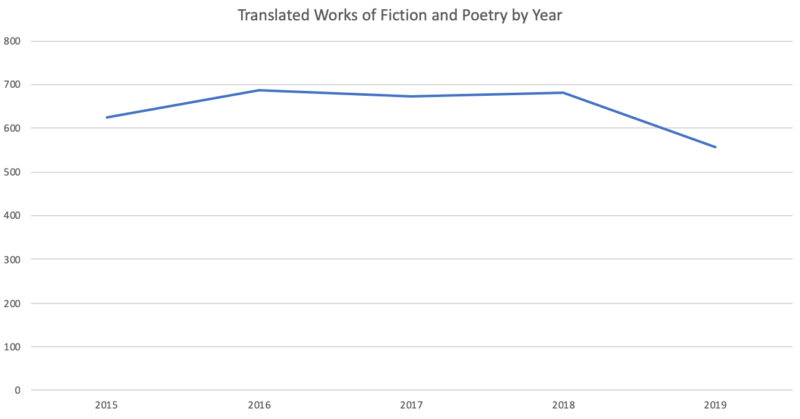

Let me build a bit of context. Here are the number of new works of fiction (and poetry) in translation published in the U.S. over the past five years:

2015: 519 (107) = 626

2016: 569 (117) = 686

2017: 530 (143) = 673

2018: 560 (122) = 682

2019: 478 (78) = 556

I must be missing things, right? Right?? If your books aren’t in the Translation Database, please add them—I would greatly appreciate it. I’m digging and digging and looking into all the presses that did 1+ translation in 2017 or 2018, but have zero in 2019, but . . . well, I could really use your help.

What a boring graph!!

I’m going to save a more detailed breakdown for next month, at which point, we’ll hopefully be up into the 600s . . . it would be WILD for the number of published translations to collapse by 18% from 2018 to 2019. WILD. If these numbers are accurate, then that is your lead story.

*

Someone asked on Facebook if I had a hypothesis about what would cause such a drop, and I replied with something about presses that had been doing a TON of translations cutting back, along with a lot of single-translation presses not coming through in 2019. But that’s not actually an answer to the question. That’s simply restating data with a couple contextual sentences. An actual explanation would provide a socio-cultural model for why these are the numbers we’re seeing.

So, instead of assuming that within a few weeks the 2019 translation numbers will stabilize, let’s just go with what we have right now: there were 130 more translations published in 2018 than last year. Why would that be?

One of the troubles of old age—which, to be fair, isn’t exactly a trouble since it makes life more surprising—is that I’ve forgotten what I’ve written here, talked about on the podcast, went on and on about to someone at a book party, or dreamt. Reality is really fluid—and thus kind of fun?—when your memory starts to glitch.

Anyway, here’s an idea (that I’ve written about before?): For over a decade—from 2001-2010—publishers of translations were able to exploit an inefficiency in the market. Any publisher willing to put in a bit of work could find a stellar book that they could buy the rights to for $1,500. And given the novelty of literature in translation (if 2019 sucked with 556 titles, 2008 was a catastrophe with only 370), you could do pretty alright, sales-wise. Not to mention, there really wasn’t much competition for grants and buzz at that point in time—doing translations was a novelty and everyone tried to support you, from indie booksellers to reviewers to foreign governments.

This has all changed.

Now, almost every translation of note is floated past a half-dozen presses, and agents are able to create auctions. . . . There are too many translations for a store the size of, say, Riffraff, to stock. The major review publications don’t pay special attention to a book simply because it was translated, instead they employ some special calculus when deciding which translations are worthy of coverage. (Q: Is it based solely on the book’s quality? A: NO. Q: Is it based on the quality of the translation? A: NOT LIKELY. Q: Is a bad book from Riverhead or New Directions going to receive a pass when the same book from Open Letter wouldn’t? A: Absolutely. Let’s not pretend the world is a meritocracy.)

There is a glut. It’s quite possible that the market can’t bear this many translations year after year. And when that’s the case? One or two books will sell very, very well (re: Elena Ferrante’s new book), and the others will all sell very modestly. The game has changed, and it’s hard to see a world in which a translation-centric press can exist solely because of its editorial chops. It’s all about signal nowadays. If booksellers or reviewers actually read all the books they could before deciding which ones they wanted to sell/review/promote, then American Dirt wouldn’t have happened.

Sorry, too soon?

*

This paragraph of Laura Miller’s very odd Slate article on American Dirt is equal parts fascinating and completely batshit:

But the most common take on the American Dirt fiasco is that it resulted from Flatiron’s hubristic failure in what the industry refers to as “positioning”—that is, communicating the genre a house considers a new book to fit into. “From what I’ve heard,” said one senior editor, “it’s a really quick, pacey, dramatic read, and there’s a whole coterie of people who will say that to their friends, and word of mouth will move across the country like wildfire.” In other words, the novel is a work of commercial fiction, much like Where the Crawdads Sing and other titles that sell in large numbers while generally flying under the radar of cultural critics and political commentators. Where Cummins’ publisher went wrong, in this formulation, was to present American Dirt as if it was also, in the senior editor’s words, “a contribution to a vital understanding of this issue,” with the implied claim of representing the issue accurately rather than using it as a backdrop for an entertaining suspense story. “It’s a commercial book that was mispositioned as literary,” another senior publishing executive observed. Flatiron’s publisher, Bob Miller, essentially acknowledged this in a statement released Wednesday, noting, “We should never have claimed that it was a novel that defined the migrant experience.” This set American Dirt up for a degree of scrutiny to which most popular bestsellers are not subjected, at least not right out of the gate. “You can’t be Twitter woke and Walmart ambitious,” the assistant editor quipped.

There’s so much wrong with the American Dirt situation right from the jump—the launch party with barbed wire, the reference to the author’s husband as an “undocumented immigrant” who happens to be from . . . Ireland, the author’s Puerto Rican grandmother serving as justification for appropriating voices and writing “trauma porn”—but the worst part of this is that for all of its mistakes and disinterest in doing the right thing both Flatiron Books and Cummins will make millions. The world is gross and rewards the wrong people.

People who use the word “positioning” as a stand-in for “tricking you dumb losers” shouldn’t be quoted on major websites. Full stop. You’re normalizing the worst aspects of capitalism in a Trumpian Age. That’s a bad look. The belief Bob Miller has that had they simply marketed this as commercial fiction instead of “literary” (what does that even mean? Corporate presses claiming books with million dollar advances are “literary” makes me gag) they would’ve avoided all controversy is such a craven and horrible thing to say. The idea that there’s nothing wrong with the book itself, just the way it was positioned is proof positive that smart book people aren’t running this industry; this is Business School talk through and through and through.

Also, Laura Miller really buried the lede here. The same acquiring editor—who “miraculously” has failed upward and is now the president of Henry Holt, which, ugh, god, c’mon y’all—ALSO acquired The Help. That book was problematic in 2009. If it had come out last year, Twitter would’ve literally imploded. Literally.

*

I can’t say too much right now, but Dalkey Archive and Open Letter have started working together; we’re exploring a collaboration to benefit both presses, and, more importantly, benefit authors, translators, and readers. But until it’s all locked down, I think I’m going to put a gag order on myself. Stay tuned.

*

Speaking of, here’s a Dalkey title to preorder from wherever you preorder your books: The End of the World Might Not Have Taken Place by Patrik Ourednik, translated from the French by Alexander Hertich.

Speaking of, here’s a Dalkey title to preorder from wherever you preorder your books: The End of the World Might Not Have Taken Place by Patrik Ourednik, translated from the French by Alexander Hertich.

I’m only a 1/3 of the way through this, so I’ll save a full recap for next month, but god DAMN, this is a breath of fresh air. The structure—111 short chapters that function like a mosaic, painting a situation instead of telling it—is so counter to MFA writing in 2020. The variety of tone and style is wonderfully refreshing, and I’m so into the idea of someone contemplating the eventual end of the world . . .

The end of the world is the least of the problems facing Gaspard Boisvert, erstwhile advisor to “the stupidest American president in history,” when he discovers that he may share the genes of a certain, infamous Austrian corporal, thanks to a dalliance on the part of his grandmother during the First World War.

Around the hapless Gaspard’s descent into amnesia and anti-social rebellion, an obsessive-compulsive narrator assembles 111 pithy chapters linked by the ultimate theme of all: the coming apocalypse. In this deadpan anti-novel, statistics and historical data are marshaled, and the divagations range over subjects as various as the history of religions, Viagra, vegetarianism and dietary taboos, aerial bombing, the Maltese national anthem, categories of suicide, varieties of stupidity, bathtubs, the critical density of the universe, pork and pigmen, and the etymology of the name Adolf.

Expect a number of posts on Ourednik (a character my students all have heard of in my “authors can be problematic” lecture) and on this book in the near future. But for now, trust me—this is really good.

Order it! But do so through my Bookshop.org Affiliate Store, because, well, I want to exploit Bookshop.org while it’s still around . . .

*

I’m not sure there’s a project Andy Hunter is involved with that I fully support. Which is a Chad 1.0 thing to say, although I want to make it clear that I don’t mean it in a mean way—I wish Andy Hunter and his various enterprises the best—I just personally have a hard time believing in websites to fix larger structural problems.

Anthony loves to remind me about the argument Andy and I had in ABQ last Winter Institute about the now-existent Bookshop.org. It was dumb and drunken and I’m 100% sure I didn’t make sense, but I do, today, on February 2nd, 2020, while watching Shakira play in the Super Bowl, feel that my knee-jerk opposition to this was pretty spot on.

(Also: What exactly is the Masked Singer? And why did this TurboTax dance ad have to happen? That left me feeling very uneasy.)

For those not in the know, Bookshop.org is a new online retailer. Think Amazon.com but with smaller discounts and shipping charges. Also: No ebooks. No The Man in the High Castle either. Like, Amazon, but more expensive and without any bells or whistles.

Gah! Having decided that I’m going to be the #1 All-Time Ultimate Best Ever HOF Influencer on Bookshop.org, I should probably try that again with a bit more positivity . . . a bit more Chad 3.0.

Are you someone who likes books but hates leaving home? Do you buy everything you can online—groceries, cologne, anything that can be shipped in a box—but feel guilty using Amazon.com instead of driving to your local bookstore? DON’T WORRY! BOOKSHOP.ORG IS HERE! An online retailer that’s WICKED WOKE. They give a portion of every sale to indie bookstores because LOCAL SELLS LOCAL Y’ALL, and you gotta keep your favorite bookstore in business no matter how odd you find their pretensions and inventory. Without indie bookstores, who KNOWS what could happen! Donald Trump could become president. Rochester’s Parcel 5 could remain an empty lot for decades! THE HORROR.

Jokes aside, Bookshop.org promised indie booksellers a dream. If you sign up as an affiliate, you’ll get a cut of every online sale through your store! And they’ll share a percentage of the rest of the sales (the general, unaffiliated ones) with all registered bookstores equally! It’s like communism, but a communism in which you take the bulk of the profits and direct them away from the people! And all of the sales? They’ll come from assholes like me who order from Amazon.com because we’re poor, follow the path of least resistance, or have no indie store nearby (no longer true for me! shop Sulfur Books!!!).

Now we have a slightly more ethical option to get books delivered to our door while we watch Netflix and Big Little Lies.

(I actually ordered a book from my own shop the day Bookshop.org launched. It hasn’t arrived yet, although the copy I ordered of the same book from Amazon.com has. I know I’m the asshole in this, but to believe that ethics are more persuasive than every other part of the consumer experience is silly. Booksellers think they can convince consumers to stop being shitty by saying “AMAZON IS BAD” really loudly; consumers need to stop consuming. We don’t need Netflix or HBO Go or most of the garbage books that Flatiron foists on the world. What’s your carbon footprint for ordering 50 copies of American Dirt that are either returned, or simply burnt in someone’s bonfire? Don’t give me ethics—give me a reason to really respect you. [Rachel: Can Sulfur Books order me a copy of Jenny Offill’s Weather? Thanks. I’ll Venmo you.])

In 5 years, if Bookshop.org still exists, I’ll . . . kiss Andy Hunter’s feet. WRITE IT DOWN. I won a $1,000 bet two Winter Institutes ago and never got paid. If in 2025 Bookshop.org is still tallying sales—and, bigger question I suppose, I’m still alive—I will kiss Andy Hunter’s feet. Both of them. Separately.

Why do I think it’ll fail? One word: Influencers.

This is a book retail website where all bookstores and, well, anyone who has a Twitter or blog or whatever?, can register as an affiliate. Just like Amazon.com but with better margins. (I think.) I registered immediately because I WANT THAT $$$$. For every sale through Chad W. Post’s Recommendations, I get a 10% kickback. Sorry: Affiliate Fee.

My “bookstore” has a picture of Busch Stadium front and center. This is how I roll.

This is also how seriously I’m taking all this.

If you envision a world in which Bookshop.org actually works, it has almost nothing to do with independent bookstores—the supposed reason it came into existence. Instead, a successful Bookshop.org is loaded up with hundreds of influencers, from Maris Kreitzman to Kim Kardashian to EVERY AUTHOR EVER, who is convincing their followers to order books there instead of Amazon so that they get a bigger cut of the pie.

I literally saw an author on Twitter explain that he wanted everyone to order his book through Bookshop.org so that he could get 10% of all sales AND 8% royalties from his publisher on those same sales. Bookselling is now an author’s side-hustle. And in a space where physical bookstores are kind of irrelevant and where celebrity is far, far, far more important. Imagine Stephen King or Reese Witherspoon or Goop telling their followers to only buy through Bookshop.org so that they can maximize their cash?

When are we going to realize that you can’t pretend your gross capitalist moment is anything more than that? (LOOKING INTO YOUR SOUL, BOB MILLER OF FLATIRON BOOKS.)

As can be expected, all the indie stores are now interrogating the idea of Bookshop.org as an unquestioned good . . . Andy Hunter’s Winter Institute speech was well received, but it took about 48 hours for the tide to turn and tweets of the “is this website actually benefitting indie bookstores?” to take over.

Lots of talk lately about “good intentions,” and it’s funny to me how Bookshop falls in line with. Reality, though, is a messy thing, and it skewers intentions very quickly, and we’re frantically trying to chase down or from what we’ve set in motion.

— Brad Johnson (@AhabLives) January 29, 2020

This all said, I have two requests: 1) Buy books through my Bookshop.org store, and 2) If there’s a god, can I have Andy Hunter’s hair?

*

In addition to talking about Bookshop.org, my other idea for the next Three Percent Podcast was all about Ferrante.

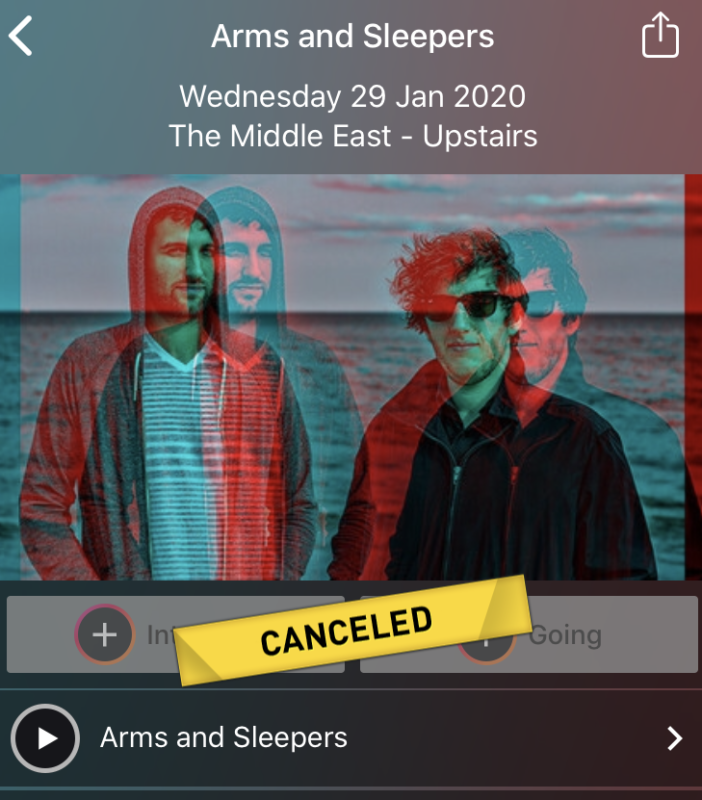

On Wednesday, I drove to Boston to see Arms & Sleepers play. Over the past few months, they’ve gone from “band I dig” to “band I listen to every single day.” They’ve become one of my all-time favorites, and I’m in love with their six-album 2020 plans—three LPs and three EPs—and the idea that they’re all based around being a Bosnian refugee and climate change. So in. 100% in.

So I drove 6 hours to see them perform Safe Area Earth.

Except I didn’t. As I crossed the MA state line, I checked my phone and found out the concert was . . . not happening.

Except I didn’t. As I crossed the MA state line, I checked my phone and found out the concert was . . . not happening.

Just my luck!

Chad 3.0 decided to roll with this, though, and just spend a night and day thinking. About words. About what it means to be a publisher. About death and life and joy and Elena Ferrante.

I can’t find reliable stats on this, but let’s start here with one premise: Each of the Neapolitan Quartet books sold 3 million copies (minimum) in English translation. So what can we expect of The Lying Life of Adults?

Here’s how my publishing experience relates to this: We discover an amazing talent like, say, I don’t know, XXXX XXXX. We pour all our time, passion, energy, money into the books we’re doing. I have the editing experience of my life making the first title the absolute best book that we possibly can. XXXX’s agent then sends a pretty direct message (although one that’s mostly conveyed by not responding to emails despite XXXX’s excitement overing having us publish future books) that no matter what we do, we’re small fry and the author’s next books need to be with a “bigger,” and thus “more important,” publisher. Because literary citizenship doesn’t really matter to people in power. They don’t actually believe in the idea that anyone can make it, that success is a magic combination of passion and luck and being that much smarter than the Big Five. Instead, agents worship corporations and don’t actually appreciate ingenuity. All that we (we being small presses) do for books and authors is nothing more than laying the groundwork so that an agent can get a big payday. This industry values the wrong values. Top to bottom.

Here’s a promise: If all agents stop sucking, I’ll never order a book from Amazon again. MARK MY WORDS.

There’s one message that’s pervasive throughout ALL of book culture: If you haven’t already made it, you can go fuck yourself. Be the one to swoop in and take over, or be the one to let everyone else profit off your intelligence and grace to make money.

This is where bitterness is born.

If only we had marketed XXXXX’s book as a fast fun commercial read instead of something literary . . . Like, screw being Twitter woke when you can get that sweet sweet blood money.

Anyway, Ferrante is Europa. And Europa doesn’t have to worry about their overall business because they have Ferrante on lock. They publish the Italian versions of her books, and the English. They have an HBO series. Book clubs love her. Millions of sales. They can literally publish 42 books of lorem ipsum and still make money in 2020. Bully for them!

Anyway, Ferrante is Europa. And Europa doesn’t have to worry about their overall business because they have Ferrante on lock. They publish the Italian versions of her books, and the English. They have an HBO series. Book clubs love her. Millions of sales. They can literally publish 42 books of lorem ipsum and still make money in 2020. Bully for them!

(Let me put this in context. If My Brilliant Friend sold 3 million copies, that’s 500 times more copies than our best-selling book, Death in Spring, has ever sold.)

How many copies of The Lying Life of Adults do they need to sell for this to be considered a “success”? More than My Brilliant Friend? That seems impossible, right? Or . . . not? I can’t project this book’s sales!

I’ve seen Charles Frazier tank post-Cold Mountain, which makes me suspicious that the new Ferrante will outsell the Quartet.

But maybe it will!

My assumption derives from the idea that every book/movie/album is its own separate thing. It has a baseline of sales based on previous success, but that’s not based on total sales of the last artwork. Sales dip. Artists have peaks and valleys. One movie/book lands, and the next isn’t beloved by Oprah. (*COUGH* AMERICAN DIRT *COUGH*) One work of art is a masterpiece; the majority are not.

So there’s no reason to expect this new book to sell more than the previous ones, right? Will every person who bought Ferrante in the past buy this? Will they all even know that it exists?

But that’s the message that this industry provides, 24/7, from most every player: Keep growing, or be forgotten. The assumption agents have that if you’re a relatively “un-rich” publishing house is that you’ll either fail (sales-wise) or be a good launching pad for “real” success with a “major press.” This is the grossest form of capitalism.

If 90% of the industry of translated literature is made of people like me, used and abused and dismissed and treated horribly by agents and foreign publishers . . . is it really a surprise that the translation numbers are so down?

I don’t want to say that agents ruined literature in translation for the common reader, but, well, a few of them really sort of did.

*

Over the month of January 2020, I finished eleven books. That would be a higher number, but I’m reading like five books at once and am about to finish all of them.

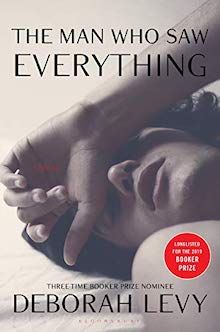

That said, my Book of the Month is The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy. I’ve been a fan for so long—Billy and Girl came out just before I started at Dalkey and I edited Pillow Talk in Europe and Other Places, which no one talks about, but maybe they should?—but I haven’t read the recent books. Despite the fact they came out from And Other Stories, and helped make AOS a major UK player. I love that and am ordering all of their titles through my own Bookshop.org affiliate store. (Or I could be a jealous, struggling publisher and tell Stefan that the Levy books he did are the minor works. Not gonna happen. Even Chad 1.0 wouldn’t do that.)

That said, my Book of the Month is The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy. I’ve been a fan for so long—Billy and Girl came out just before I started at Dalkey and I edited Pillow Talk in Europe and Other Places, which no one talks about, but maybe they should?—but I haven’t read the recent books. Despite the fact they came out from And Other Stories, and helped make AOS a major UK player. I love that and am ordering all of their titles through my own Bookshop.org affiliate store. (Or I could be a jealous, struggling publisher and tell Stefan that the Levy books he did are the minor works. Not gonna happen. Even Chad 1.0 wouldn’t do that.)

This novel though? BRILLIANT. The voice, the narrative game that’s played with reality, memory, and death. There’s nothing else I DEVOURED the way I devoured this over a three day period.

I both checked this book out from the Brighton Library and bought the Audible audiobook. For a few days, I heard Saul’s obnoxious voice in my head, and saw it in the text. The high concept behind this book and the way in which that narrative unfolds, with time jumps, memory, hospitals, and death, is pitch perfect.

This is dumb and trite, but I really, really love female writers—especially those living in the UK. This book lead me to Nicola Barker and Old Filth and a desire to shy away from Eastern European males . . .

*

Music always comes back alive in January. This month there were four new albums from artists I already loved—Dan Deacon, Arms & Sleepers, Holy Fuck, Torres—and yet, the two big surprises were Football Money by Kiwi Jr. (do you love Pavement/Ought and lines like “I miss our talks over coffee / nothing says home like a basket of white folded shirts”?) and Bombay Bicycle Club’s Everything Else Has Gone Wrong.

If I have to choose an album of the month—which I’m going to do as a counter to the “MOST ANTICIPATED ARTWORKS WE DON’T KNOW ABOUT BUT WANT TO KNOW ABOUT BECAUSE THEY’RE COOOOOOOOOLLLLLL” lists—it would be Everything Else Has Gone Wrong.

This is mostly due to my interpreting this album as a “getting out of a depression” album, but also, this song rules.

*

Runners-up in my book (non-Open Letter titles) and music art for January:

- Prague by Maude Veilleux, translated from the French by Aleshia Jensen and Aimée Wall

- Our Dead World by Liliana Colanzi, translated from the Spanish by Jessica Sequeira

- The Colonel’s Wife by Rosa Liksom, translated from the Finnish by Lola Rogers

- Good Will Come from the Sea by Christos Ikonomou, translated from the Greek by Karen Emmerich

- Conversations with James Joyce by Arthur Power

*

In terms of TV, which I’m perennially behind on, I’m so into Big Little Lies that I’m surprised I’m actually taking time away from my binge to write this nonsense.

*

For music, aside from Everything Else Has Gone Wrong (which I’m listening to now), here’s my list of January favorites:

- Dan Deacon, Mystic Familiar

- Holy Fuck, Deleter

- Kiwi Jr., Football Money

- Arms & Sleepers, Safe Area Earth

- Destroyer, Have We Met

- Torres, Silver Tongue

Leave a Reply