Another take on “The Invented Part” by Rodrigo Fresán

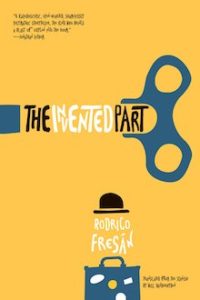

The Invented Part by Rodrigo Fresán

translated from the Spanish by Will Vanderhyden

552 pgs. | pb | 9781940953564 | $18.95

Open Letter Books

Reviewed by Tiffany Nichols

Imagine reading a work that suddenly and very accurately calls out you, the reader, for not providing your full attention to the act of reading. Imagine how embarrassing it is when you, the reader, believe that you are engrossed in a work only to have the work identify and criticize your lack of attention. Yes, my phone was next to me at all times while reading Rodrigo Fresán’s The Invented Part, and often I was tempted to dash off 140 character reactions to the work, only to be shamed by it a few lines down in the text. This is part of the charm that is The Invented Part. Weaved throughout it are reflections and criticisms of our shift from the written word on a page to a screen. The timing of the publication of the English translation is perfect in light of the behaviors of our current news cycle, the relationships our elected officials have with Twitter, email, the methods used to inform themselves of “reality,” and our current dilema of phrasing through what is real and what is fake.

The Invented Part can be summarized as creating a discourse around the question: How do writer’s view their craft, reality, and relationships with readers and with those individuals who play a role in their lives? The response is addressed through distinguishing the invented part—the part that is created by a writer—and the real part—the reality leveraged by the writer. Through this work, the protagonist, The Writer, draws or focus to the question of our relationship with writers, books, and technology and the literary industry, which frustrates The Writer and causes him in turn to question the role and future physical presence of literature. The Writer is disillusioned with the state of the literary industry and thus decides to travel to CERN and merge with the Higgs boson, resulting in a transformation into invisibility and omnipresence. The publication of the English translation of The Invented Part also coincided with the five-year anniversary of the announcement of the discovery of the Higgs boson particle, also known as (to the dislike of most physicists) the God Particle and largely believed to provide matter with mass.

My only disappointment came in reading the summary of the work on the book’s cover, as I approached the work with excitement believing that it would tackle such a complex physics concept within the literary sphere. As I worked through this quite long piece of literature with this expectation, I reached the end with great disappointment on the topic of the Higgs boson. It appears that the transformation into the Higgs boson was merely an anthropomorphism for omniscience. Being that most people would likely believe that something called the “God Particle” would explain the entire universe, the reference works in this sense because The Invented Part’s main tool is omniscient narration (with the ability to change reality).

Divided into seven parts, The Invented Part begins with a section entitled The Real Character, which is focused on a family (The Young Man, The Young Woman, and The Boy), which is formed due to a common love for a writer’s work and ends in separation, although both parties continue to read the same works by the writer. Part Two focuses of the unusual experience of The Young Man’s and The Young Women’s stay at the home of The (disappeared) Writer during the making of their documentary film on The Writer’s life, accompanied with an excursion through the early life of The Writer’s eccentric sister, who marries into a family (based in the land of Abracadabra) that is hard to distinguish from the Kardashians, or a family with many company brands (think steak, hotels, failed universities) and vast amounts of property, but with no indication of how the money is really made. Part Three focuses on The Writer’s experience at a hospital as he approaches the age where pain is now a matter of death or a non-issue and is no longer something that can be casually ignored. Part Four contains The Writer’s personal notes for a work in development concerning the relationship between the Fitzgeralds and the Murphys, written in the biji style and defined as “curious anecdotes, nearly blind quotations, random musings, philosophical speculations, private theories regarding intimate matters, criticism of other works, and anything that is owner and author deems appropriate.” The focus in Part Five is the relationship between a father, a friend of The Writer, and his son through the father’s relationship with music during his teenage years. Part Six brings us back to The Young Man and The Young Woman during an encounter after their separation, where they meet on the stairs to a museum. Finally, in Part Seven, the reader experiences The Writer’s motivations, insecurities, and what appear to be the beginning of his first work after the disillusionment and transformation.

It was no easy task to get through The Invented Part, mainly because the work presents life experiences in a way that the reader cannot help but reflect on each example, instance, and occurrence presented in the work in real-time. Fresán does this by presenting the reader with familiarities—Pink Floyd, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Bob Dylan, Mary Shelley, David Bowie—and uses those references to call upon reflection of these bodies of work to explore both our relationship with literature and books surrounding us and the writer, and the writer’s relationships with the same, and with the feeling of actual experience rather than that of a college lecture. Fresán awards the reader who is not only well-read but also well-aware of music originating between the 1960s and 1980s. For example, the following is a list of the literary references by author I noted while reading the work, but I am self-aware enough to know that I did not catch them all.

Borges

Faulkner

Fitzgerald

Dostoyevsky

Mann

Bronte

Nabakov

Burroughs

Beckett

Lovecraft

Tolkien

Quinn

Delillo

Dante

Shikibu

Updike

Conrad

Vonnegut

Hemingway

Wolfe

Lowry

Bradbury

Shelley

Huxley

Gaddis

Flaubert

Amis

Further, Fresán has a special way of describing (inventing) the normal and mundane. For example, airports in The Invented Part are not just airports:

Airports are like enormous and devouring leviathans run aground on the shore of all things, too heavy to be pushed back out to sea. Airports are like cathedrals of an always late and retarded faith . . . and airports are the sanctuary where everyone prays and begs that their flights leave on time, and that they arrive on time, and that their luggage doesn’t disappear in some wrinkle in space-time, and that everything that goes up does come down but doesn’t fall amen. Airports are like hospitals: you know when you go in but not when you’ll come out and you sit there like something patient, something passing.

And oversharing and not just oversharing:

Being missed has gone missing. Being familiar with so much doesn’t mean knowing more. There was a time when the definitive proof of success was the very ability to disappear, to be impossible to find, to have nobody know where you are. To be unreachable. To be outside everything.

Lastly and importantly, The Invented Part contains warnings for the future of the book in our age of technological screens and our inability to be disconnected. For example, it is stated that:

E-readers, supposedly, help to facilitate and accelerate the reading experience, but actually it seems, end up removing the desire to continue readings. But—breaking ancient news, stope the presses—we still read at the same speed as Aristotle. About four hundred fifty words a minute. So, all that external electric velocity at our disposal ends up colliding with our more deliberate internal electricity. In other words: machines are faster and faster but we are not. We haven’t gained much and, along the way, we’ve lost the exquisite pleasure of leisure, which is how and where the stuff of hopes and dreams is made. We live and create, determined to increase out machines’ capacity to store a number of books that we’ll never be able to read. . . . It seems to me that the paper book is nearer out rhythm (there are nights when I deeply envy the environment of the nineteenth century when it comes to reading nineteenth-century novels by candlelight).

In closing, The Invented Part is a work that I will repeatedly refer to, interact with, and re-read as it captures and questions my relationship with literature in magical and embarrassing ways that will continually change as I refamiliarize myself with the classics, expose myself to new works, and go through the process of aging. This tome will be proudly placed next to my copies of 2666 and People of Paper, both of which also relay the same essence, but through vastly different methods.

Leave a Reply