Poetry Presses and Radical Idea #1

Thanks to a different writing deadline, the revamping of this website (still a bit of a work in progress), and trips to Chicago, Houston, and New York (with another NY trip later this week), I’ve fallen slightly behind with my weekly missives, so expect a bunch of these to drop over the next week or so.

First up, I want to finish off my month of poetry reading with some general poetry stats from the Translation Database, followed by short bits about the final two poetry collections I read last month and then the beginning of a crazy new series.

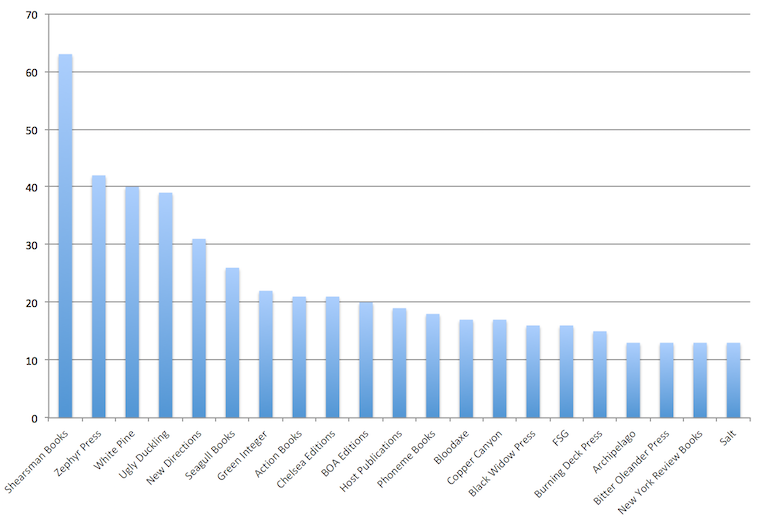

First up, in honor Poetry Month, I thought I’d run a chart of the presses who have published the most collections in translation since we started tracking things in 2008.

I’m not sure how many people would’ve guessed that Shearsman Books would be on top of this list, but they’re truly dominating. Since 2008, they’ve brought out 63 titles–21 more than Zephyr Press, who is followed by White Pine, Ugly Duckling, and New Directions.

Overall though, this is a great list of phenomenal presses, who have been responsible–for years–for introducing English readers to international poetry.

For anyone interested in the raw data, we have logged in 1,023 collections since 2008, and these twenty-one presses have published 495 (or 48%) of them. That’s pretty incredible. And much more concentrated than what you’d find if you looked at the top twenty fiction in translation publishers. (I think. Maybe that’s something to look at in a future post.)

*

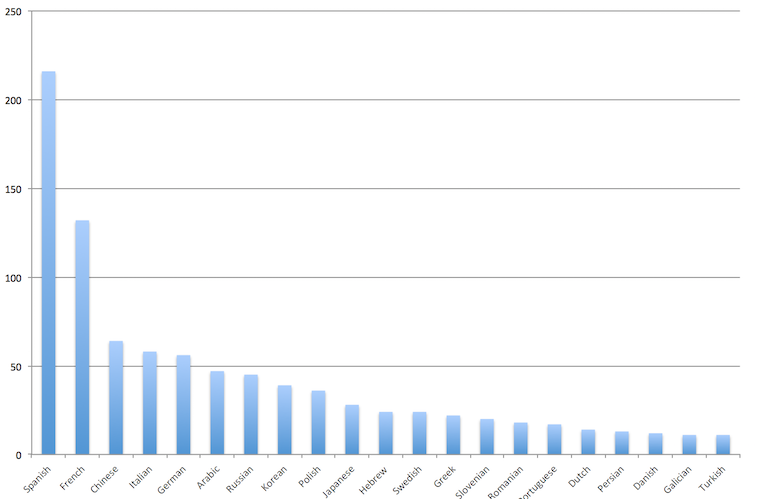

The other chart that I’m most interested in is the breakdown of which languages these collections are translated from.

I don’t know if this is interesting or not. Spanish is sooooooo far ahead of everything else–216 titles, with France in second at 132–and after those two languages, everything is all bunched up. How many people expected Chinese to be the third most-translated language when it comes to poetry in translation? (Actually, might make sense! Zephyr does a ton of Chinese translations–22 to be exact–and are second-highest in the number of poetry translations.)

Although this is all muddled, it is curious that three East Asian languages are on here: Chinese (64), Korean (39), Japanese (28). And Galician made it! Galician!

My gut feeling before running this was that Eastern European languages would fare really well on this. There’s Polish (36), Slovenian (20), and Romanian (18). Nice to see Arabic (47), Persian (13), and Turkish (11) on here as well.

*

There are lots of perspectives on the process of translating poetry: that it’s sort of a linguistic game, that you have to choose what you’re going to retain (meter, rhyme, meaning), that it’s not really possible to translate poetry in an accurate way, that the fact that every poem can be translated a million different ways is fascinating and highlights the art of translation, etc.

Marc Vincenz illustrates various aspects of this with his two translations of Klaus Merz’s four-line poem, “Research Shows.”

The master is badly beaten,

his heart is sadly searing.

He shows his randy teeth

and chomps the candy dog.

Which is pretty different from

The master is maligned,

his heart is sore.

He bares his canines

then bites the pooch some more.

The first version has a very different rhythm than the second, which is much more varied. The second has the “sore” “more” rhyme, whereas the endings of the last two lines in the first version–“teeth” “dog”–is a bit more evocative.

Sticking with meaning for a second, there’s quite a difference between “his heart is sadly searing” and “his heart is sore,” although arguably, the weirdest difference in this regard is “chomps the candy dog” (candy?) versus “then bites the pooch some more.”

Everyone should read Eliot Weinberger’s Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei.

*

A couple posts ago, I wrote about the difficultly of getting into poetry without having the critical language at hand; at the same time, reading this critical discourse can be really entertaining–sometimes even more so than the poems themselves.

Here’s the sort of thing I was talking about:

Detela’s technical choices are, in a few poems, so strongly marked, we had to assume they were fully intentional, even if his original motives were unclear. For example, poem #2 is structurally a 17-syllable haiku written in amphibrachs–i.e., a strict meter in three-syllable feet with the stress on the second syllable of each foot. [. . .]

In the end, it was not hard to express the ideas in #2 in 17 syllables simply by staying close to the meaning of the Slovene, but the rhythm in English fell naturally into a mix of amphibrachs and anapests (three-syllable feet, stress on the third syllable)–in any case, there is a strong rhythm based on traditional three-foot meters.

I can only hope that the confused respect I experienced when first coming across amphibrachs is similar to what my friends feel when I start going on and on about xWOBA and xFIP and o-swing rates and how you can use these elements to analyze a baseball player.

*

Speaking of baseball, over the next few posts, I’m going to straight-up rip off one of my favorite baseball writers, Sam Miller. Last week, he wrote a series of articles for ESPN featuring “radical ideas” about how to restructure baseball on a global level. These were crazy, untenable ideas, allowing every team to make the playoffs and allowing teams to bid for more home games.

These are clearly crazy ideas, but in their craziness, call into question the underlying assumptions about how the baseball industry should work and brings to the forefront some intriguing questions about what it is we want out of the sport itself.

This is something that would be fun to apply to publishing! Especially small press, international literature publishing. I don’t think I can come up with anything as compelling or strange as what Sam did, but I do have at least one radical idea that’s fun to think about.

Saving that one for later though. Mostly because it ties into the Nobel Prize mess, and I’m waiting for all the hot takes to come out first. I mean, I don’t even know if LitHub has put out a listicle in defense of listicles about Nobel Prize non-winners. That’s something I don’t want to miss! (Kidding, y’all! LitHub does what it does better than anyone. And aside from BookMarks and the listicles, it’s really good. It is funny to troll them now and again though, since they get so defensive.)

Today’s Radical Idea for Translation Publishing is the idea of a National Money Pot for Translators.

The Problem: Most presses that publish translations are very small, and their books don’t sell very well. At the same time, because translators want to get paid based on effort and not creative merit (they get paid by word, whereas authors get paid by projected sales), small presses are asked to pay just as much as the larger presses, resulting in an incredible imbalance between risk and reward.

The Solution: A national pot of money that is divvied up every year to translators, providing additional funds for translators whose works didn’t sell as well.

The System: For every translation that’s published, a small part of the revenue from all sales–say 5% of received revenue–is put into a national pot. After a title has been available for a year, the translator/publisher submits sales information to those in charge of this pot of money and, based on an advanced formula involving overall sales of translations, average advances to translators, and expected royalties, these money-pot holders give out cash awards to supplement the original fees.

The Benefits: Translators could work with smaller presses who can’t afford to pay translators what they desire, since these translators would end up receiving supplemental income from this National Pot. Publishers would be incentivized to do more translations, since this financial burden would be slightly shifted–away from the press itself, and onto the overall market for international literature. Contracts could become much more loaded on the back-end–smaller initial fees, larger royalties that start accumulating from the very first sale–knowing that there would be a lump sum coming from the National Pot.

How Much Money Are We Talking?: Let’s say that there are 680 translations a year that sell an average of 750 units. And 20 that sell an average of 7,500. For both, the average retail price is $14.95 with a 50% discount to retailers. That results in just under $5,000,000 in revenue, 5% of which would be $246,675. If you reallocate that evenly, every translator would get an additional $350. But if 80% of this goes to the 20% of the books at the bottom, then the 140 translators whose books were most “hopeless” (sales-wise), would receive $1,400, with the translators whose books will sell, would get far less.

This Doesn’t Seem Very Impressive: What if we add in that other parts of the book industry contribute as well? What if Amazon dumped in .5% of the sales revenue for every translation they sold? That initial $5 million almost doubles. Agents should contribute as well. They kick in a small portion of their cut of an author’s advance. Usually, this would be nothing, but in those rare cases where an international author gets a $1,000,000 advance, the agent could end up giving $7,500. Which sort of adds up. And what if there were a few philanthropists out there who want to support translators on a broad basis? Get a few people to donate a million each, and you can get the pot to a much more significant number.

What if the Pot had $1,000,000 a Year?: Then the payment to translators of the 20% of books at the bottom–the works of poetry, the challenging 700-page experimental novels–would receive $5,714 each. This is game-changing money. This is when someone like Open Letter can take on a 1,000 page book that deserves to be in print, but would otherwise cripple the press for years. Besides, who doesn’t want to take money from the rich and successful and give it to those who are grinding but not in a position to catch a financial break?

Why This Will Never Happen: You think anyone would contribute to the greater good? Willingly? Hah! I wish I had a scam with a bridge or a foreign fortune that I could sell you on. As much as this industry should be a collaboration, it will forever operate under very capitalistic systems. If you find the book that sells a lot, you deserve all the profit. (Even if the book’s success has less to do with your skill in acquiring and editing, and more in the success of your past books that have created certain perceptions while funding extensive marketing attempts.)

Why It Would Be Great: Because the more financial relief there is for smaller presses, the more titles that would be published. The more titles published, the more jobs for translators. This would also allow for more risks, ensuring that we’re getting a huge variety of books from around the world, and not just the ones that editors think will be mega-successful. It also opens up a space for the “middle-class” of literary translators. The top-tier of recognizable names will always be sought after, and their fees paid in full; the recent graduates and up-and-coming translators trying to build a resume at the expense of being paid in full will also always be in demand. The workhorses–the translators with a lot of experience, but no breakthrough hit (the relationship between the translator and the book’s success being tenuous, but something that every translator will cling to when the book is a best-seller, and deny when it sells a routine 750 copies)–will struggle in an environment in which the total number of translations is decreasing. Especially if the only books that are greenlit are the ones with the highest profit possibilities. (High sales potential + brand name translator = YES; decent sales + low translation costs = YES; Modest sales + professionally paid translator = HELL NO.)

How This Relates To Poetry: Wouldn’t the books at the so-called bottom–the ones receiving the most from this Money Pot–be poetry collections? Wouldn’t we be taking from prose to give to poetry translators, translators who are frequently paid in pizza and free copies of the book they can sell at readings they organize? Isn’t this a good thing?

A good article, though, since the economics publishing ANY poetry book, regardless of the language of origin, is pretty much not really economics at all, it’s difficult to make some kind of special case for making it even slightly more rewarding to publish poetry in translation.

But hey…