The Crime in the Data

A couple weeks ago, writer Kári Tulinius asked me for some information on how prevalent crime novels are in what gets translated. As with most statistics related to literature in translation (and/or the book industry in general), the correct answer was, “uh . . . no idea. Maybe a lot? Sure seems like it . . . So, yeah.”

I hate giving answers like that. It forces me to acknowledge how much more complete Publisher Weekly‘s Translation Database could be. (Quick note: There is room for expansion, but there is some balance between being redundant of other databases and providing some unique set of books/information. Not to mention, I do this all by hand and there are limits to how many hours there are in a day and days in a life. In other words, we can’t do everything.) The whole point of the database was to finally provide some clarity as to what exactly is being translated—data that could theoretically be analyzed to understand trends in publishing, to try and grasp why certain languages or types of books were making it into English while others weren’t.

And doesn’t genre play a huge role in this? Just look at the “Nordic Crime” boom post Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. (Which also may have kicked off the “girl [preposition] noun” titling technique? Girl on the Train, Girl in the Window, Girl in the Dark, Gone Girl, Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, etc., etc.) The total success of Stieg Larsson’s series launched the international careers of dozens of Nordic crime writers. Or, transformed them from a safe midlist-bet into something exotic and sought after.

Given the success of Europa Editions (which, Ferrante aside, does a ton of crime novels), Soho Press, Bitter Lemon, AmazonCrossing’s “Hangman” series, and so many others, it really does feel like everyone’s on the lookout for a great crime series—and that that’s where the money is.

The more I’ve thought about this, the more I want to know just how many crime titles were being published in translation. So, I counted.

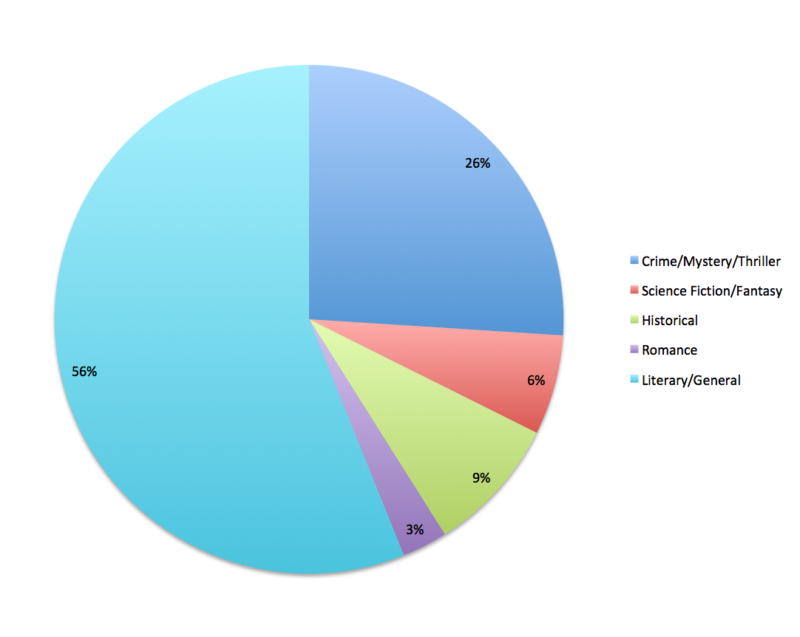

Quick Methodology Explanation: I took the ISBNs for all books in the Translation Database for January-May 2018. Then I put them in one by one into Ingram’s iPage (or ipage? This feels like an Apple trademark issue) to see what BISAC codes were listed. (For the layperson, a BISAC is basically just a categorization code, like “Fiction/Mystery & Detective/Amateur Sleuth” or “Fiction/Historical/Romance.”) If a crime/thriller/mystery/detective BISAC was listed, I coded that book as “crime.” In order to give the pie chart below a bit more flavor (groan), I also kept track of science-fiction/fantasy, romance, and historical. Most of these were pretty easy to slot into a genre, but if something was historical AND romance, I put it in romance. And I put “Fiction/Myths & Folklore” under literary instead of fantasy. You could have quibbles. I don’t really care though. This is a good starting point, both because it has real titles and numbers associated with it, and because it fits in with what most people would’ve guessed.

This feels right. A full quarter of the translations published so far in 2018 fall into the crime genre, with historical (very muddy category, but let’s leave that for now), and science-fiction clocking it at 9% and 8% respectively. Romance is a mere 3%, although to be fair, there are only so many trite Marc Levy books out there to translate.

What would be interesting is to try and distinguish between “general” titles and “literary” ones. Right now, this is a grab bag—if a book isn’t assigned one of the other genre categories, it goes here.

Actually, who cares? That’s stupid. Genres are kind of stupid. I know they’re useful in a general sort of way, like saying a particular band plays jazz versus punk rock. But this categorization is also kind of reductive and lame. So many of the best books utilize tropes from various genres. Good books need not stay in their lane. So why reinforce this at all? Wouldn’t it be more fun if all books/movies/albums were just grouped together in a way that didn’t imply any sort of hierarchy? (Just look at the prominent place of “fiction/literature” versus “romance” in most any non-genre-specific bookstore.)

Besides, “crime” is a broad-ass category. This includes detective novels, noir, thrillers, general mysteries, heist books, military espionage, spy novels . . . and more that I can’t remember. How is that really a genre? Almost as silly as grouping hard science-fiction together with books about elves and Quidditch.

Then again, I’ve completely given up on reading copy before picking up a book or watching a movie. I might be an anomaly in this.

* * *

That said, I’ve been loving the shit out of some crime novels recently. I feel like some dozens of episodes ago on the Three Percent Podcast Tom told me a story about his dad (?) making a comment about how you read things like Nabokov when you’re young, then, as you age, you just want a relaxing, entertaining crime novel.

I don’t know that I’d go that far—or maybe, I’m just holding on to the hope that as I age I’ll still be interested in being challenged by art instead of pacified by it—but there is something to be said for staying up all night with a “page-turner.”

Which is why, in this month of busy, I decided to read a couple recently published “crime” books in translation.

Allmen and the Dragonflies by Martin Suter, translated from the German by Steph Morris (New Vessel Press)

Last month I was on a panel at the Los Angeles Times Book Festival and had the chance to hang out with Ross Ufberg from New Vessel—and his brother—at their booth. It was a ton of fun, and not just because we met Booger from Revenge of the Nerds at the main LA public library party. (I’m willing to bet that the Revenge of the Nerds trilogy [?] doesn’t fit so well with 2018’s comedic standards. I’m also willing to bet that Google could find me a hot take from The Ringer about this if I ever decided to look for it. Rule whatever of the Internet: Not only does everything you want to search for exist, but someone’s written a 2,000-word thinkpiece about it. And someone else has written a counter. And both sides have blocked each other on Twitter.)

ANYWAY. One of Ross’s brother’s techniques for selling New Vessel books was simply to invent random comparisons to other books.

Max: It’s like The Little Prince meets Harry Potter.

Chad: [Whispering] Have you read that?

Max: [Whispering] Not a word. [To Customer] That one’s like The DaVinci Code with more science-fiction.

Customer: Why don’t I take both?

This is where we’re at in terms of false representation and PR circa 2018.

I can’t remember what he said about Allmen and the Dragonflies, but “relatively quiet, character-driven heist novel reminiscent of Albert Cossery that revolves around the real-life theft of some Émile Gallé vases” was most definitely not it.

This isn’t the easiest book to craft a catchy pitch for, but basically it’s about a morally ambiguous layabout squandering his inheritance and stealing precious artifacts and fencing them to his disreputable antique-dealer friend. Trying to pay off some of his more serious debts, he filches some Gallé vases that had already been stolen. This opens up a serious opportunity to screw over everyone and come away with much more cash.

It’s not a ground-shattering book by any means, but it’s far less pretentious than Cult X (last week’s book, also technically a “crime” novel), quick-moving, and a decent enough set-up for the rest of the series.

I’m going to come back to this later, but one of the fun aspects of this book is that Allmen is a dedicated reader. That’s basically all he does.

Even today Allmen read anything he could lay his hands on, world literature, the classics, the latest titles, biographies, brochures, instruction manuals . . . He was a regular in several secondhand bookshops and had been known to hail a taxi when he saw books in a trash heap so he could take them home.

Allmen had to finish a book once he had started it, even if it was terrible. He did this not out of respect for the author, but out of curiosity. He believed that every book held a secret, even if it was only the answer to the question of why it had been written. He had to discover this secret. So really it was not reading Allmen was addicted to. He was addicted to secrets.

There’s something fun about characters who are defined in relationship to their reading habits (either what they read, or how often), and conversely, there’s something fun about characters who are absolutely disinterested in the written word (like the protagonist of Stone Upon Stone).

I’ll definitely read the next book in the Allmen series when it comes out.

* * *

Radical Idea #3: There Are No Numbers

Despite all my love for data and statistics, there’s something incredibly freeing when you have no idea of the bigger picture and are forced to just try and make sense of the patterns before you. What would the book world be like if you had no bestseller lists, no BookScan, no idea how well anything sold (or didn’t), no past data about profitability or company size or whether or not an author’s last book caught on or was an InstaRemainder? What if books were judged solely on the interior content with none of this business-driven paratext?

Let me try and back into this radical idea from a couple stories about sports (assuming I live in a world of no data, I have no idea just how much our audience doesn’t give fucks about sports):

Watching baseball without cumulative stats makes it incredibly difficult to tell who is actually good and who isn’t. To put this in perspective—and without using any advanced stats—a player with a .300 batting average is great, whereas someone with a .270 is merely good. Given that most players have about 48 at bats every two weeks, the difference between a .300 and a .270 hitter over that period is one hit. One! So if you’re watching these two players play—every day for two weeks—how likely are you to be able to say, with complete confidence, which one is the “all-star” and which one is pretty good? On the flip-side: If you already know which player is the better hitter, how likely are you to focus on that player’s successes and downplay the other player’s failure? This is only natural, this is how our brains process patterns, but it’s weird how much we favor the player we “know” is good, even when we can’t tell through our individual experiences.

Skipping all the contextual details, this past weekend, I spent a lot of time watching the NBA playoffs from a seat where I couldn’t possibly read the score. It was amazing! I just watched the game, sort of had a sense of who was winning and losing, and then, every quarter or so, would check the actual score and find out how completely wrong I was. Rather than being frustrated, I found this incredibly liberating, since I could invent my own storylines, guess at everyone’s statistics, and just enjoy the game itself, in a near context-free environment.

I want something similar for books. It would be really interesting if booksellers, reviewers, and the public bought/promoted books without the particular cues that drive a lot of our decisions.

Yes, I know the idea of eliminating all numbers is impossible and foolish, but there’s something about this sort of flattening that I find appealing. It would be like walking into a bookstore in which there were no categories, every cover was white, and jacket copy was written in invisible ink. HOW WOULD I KNOW WHAT I’M SUPPOSED TO BUY AND READ AND LOVE? And how incredibly freeing would that be?

* * *

Radical Idea #4: All Book Reviews Are Paid For

This idea sort of follows on the last . . . What if all book reviews were open to the highest bidder? For instance, the New York Times can announce tomorrow that they have 14 review slots (8 full-length, 6 in brief) available in the August 1st issue. If you want a book covered, you submit a bid by Friday, and the top bids will have their books reviewed—regardless of what they are.

I know this sounds insane, but bear with me, the game theory of it all can get really fun.

First condition is that this is a double-blind bidding process. The book reviews have no idea who is bidding and for which books. The publishers (or wealthy self-published authors?) have no idea what the other bids are, or what these slots usually go for.

Second condition is that all review outlets would collude and run this exact same sort of bidding process. Sure, sure, collusion is illegal, but that is the pre-Trump world. Now it’s just something that’s endlessly investigated or “frowned upon.”

Just think of the benefits! So many review outlets would suddenly come into existence since these payments would far exceed the amount that publishers spend on advertising in the current outlets. It would transfer money from big-wig, rich shareholders (gross) to reviewers and media outlets. It would allow publishers a legit shot at getting into a massive publication with their lead title. Maybe . . .

One more condition: If you win a bid, you are obligated to pay for it. That adds a little game theory wrinkle to everything. Say you have $10,000 to spend on a book. (An incredible amount if you’re not a corporation generating bling for old white dudes.) You could: A) put it all on the New Yorker, B) see if you can squeak in with a low in brief bid for the New York Times, but throw a bunch of cash at an intellectual journal that would “get” the book and promote it to an audience that could teach it for ages to come, or C) crop-dust the world and put $500 bids out to 20 publications with hopes that you score on a half-dozen and this gets the word-of-mouth going. This is a hard choice!

Also, publishers would be able to quickly put a price tag on a review. How much is coverage on NPR worth? Exactly this much! It would take maybe, maybe a year to figure this out. And that’s valuable.

And how crazy would it be to see an entire issue of the New York Review of Books featuring only titles from Harlequin?

Granted, the biggest of the big would be able to deep pocket the shit out of this system, but at the same time, that could backfire—you might pay for them, but the reviews are completely objective. Maybe even more objective than they would be if there weren’t money on the table. Knowing that you paid $15,000 for a review makes me feel less bad about taking a shit all over your upmarket novel that pretends to represent everyone, yet speaks to no one.

Mostly though, this would be fun because it would completely reinvigorate reviewing culture. And move cash from entities whose motives are generally disgusting to organizations that are at least somewhat more deserving.

* * *

I can’t understand this movie trailer. Who shoots a gun like that? In case this isn’t clear, the guy from Star Wars is holding the butt of the gun with his right hand and pulling the trigger with the pointer finger on his left. What sense does this make? It’s so inefficient! No one needs two hands to shoot a gun. Can someone please explain this to me?

* * *

Ivory Pearl by Jean-Patrick Manchette, translated from the French by Donald Nicholson-Smith (NYRB)

This is sort of like John LaCarré meets André Malraux with a little Jean Echenoz thrown in for fun.

Fuck it. I suck at this game.

Although the Echenoz is a legit comparison in my mind. The other Manchettes I’ve read (only a couple, I’m not as knowledgable about his work as Tom Roberge is) aren’t quite as global as Ivory Pearl, and it’s in this global scope that the Echenoz comparison makes the most sense. Take Special Envoy for example. That book includes a bunch of characters all tied into a large, wooly plot. As a result, the narrative jumps from one POV to another like a teenager on YouTube, with each chapter focusing on a interaction between two characters that adds a bit of intrigue while also advancing the plot.

There’s also something similar about the tone that both authors use. Manchette’s plots are much bloodier, but in the non-violent sections, there’s a sort of effervescence that drags the book out of its noir trappings into something decidedly less grim. It makes his novels much more fun to read than if they were mired in their own serious, bloody plots. It’s a hard thing to pull off, but Manchette makes his characters so much more than what the espionage context demands of them. Characters are obsessed with jazz, or hate it. Ivory Pearl is given a book every year from her adoptive father/handler that she’s expected to read. This is what transcends the genre, to go back to a way earlier point.

Two other things:

It sucks that this book wasn’t finished. It stops right at the point in which the plot is most convoluted, chapters before all the double- and triple-crosses all unwound themselves. Right before the notes explaining what Manchette was planning, the reader is totally unsure of who is on who’s side, which is great when you’re reading a 300-page book, but less so when you have to digest the digest to see how things were supposed to resolve themselves.

And: These are the best translator footnotes ever. EVER.

[In relation to Ivory Pearl’s complex flight path from Miami to Cuba.] Readers with a good atlas will soon realize that Ivy’s flight from Miami to Cuba follows a rather fantastical route. Let me remind them that they are reading, in effect, an unrevised manuscript.

[Main text: “In Europe it was still night, people were sleeping in North Africa likewise.”] In point of fact, in Europe and North Africa it would have been the afternoon! It is unlikely that the author would have allowed factual errors of this kind to survive publication.

This is one way to address mistakes in the text without technically changing them, but with a certain panache that’s really attractive.

I don’t have anything more to say about this book other than reiterating my desire for someone to publish an English translation of Manchette’s essays on crime novels.

* * *

Way back in the first post that I wrote in this series, I mentioned how we had switched from cable to PS Vue. This has been an interesting experience, mostly because the PS4 is CONVINCED that we live in Portland, Maine. Not even the cool Portland! Every time there’s a local commercial slot, we get this terrible ad for Maine booze in which an aging mother dreams of her daughter coming to visit and the two of them getting loaded on the front porch on Portland distilled spirits and bonding over the general injustice in the world. It’s like a sad indie movie. I keep expecting Catherine Keener to jump out and pound a weak mimosa with her clearly clinically depressed mom.

Also, I’m pretty sure the Russians Hackers have taken over all our shit. And have some weird obsession with crab.

* * *

I think I’m done with the Radical Ideas series. I have no idea what might take its place, although to be honest, I have no idea what any of these posts will look like before I start writing them. But the Radical Ideas are over for sure.

Sam Miller’s “Radical Ideas for Baseball” (yes, I know, it’s always baseball) was my inspiration and I thought it would be fun. Fun to try and figure out some weird shit that would shift the industry as a whole in a couple of different directions. But as I went along, those directions became the primary engine for the ideas, which, paradoxically, kills the joy of coming up with the ideas.

If you look back over the four ideas, the desired end-goals are pretty self-evident: a level playing field so that a press like Open Letter can succeed on a scale equal to the quality of the publications, and an industry that’s actually fun again.

Publishing is at the crux of so many various fields and ideological concepts. There’s the idea of the artist creating something that explains humanity to itself and lasts. There’s the business aspect in which that same author is nothing more than an asset filed away into a larger portfolio. There’s the sturm und drang of investing a lot of money in something you believe in, yet being forced to acknowledge that it might be completely ignored for no rational reason. In baseball you fail 75% of the time. In publishing, it’s more like 85%. And yet.

A lot of people come to publishing with idealistic ideas that are sometimes naive (“I want a job reading all day”) and often overly optimistic (“If we publish the best books, they’ll find a wide audience through some combination of quality and gumption”), but, for worse, these ideas are generally shattered a few months into their first internship. Again: This is an industry in which most authors never find a publisher, most published books don’t find an audience, and most financial successes are just a flash in the pan.

This would be OK if it wasn’t also an industry in which modern MBA ideas dominated the landscape. Or any MBA ideas, to be honest. When you’re dealing with real art—which I’ll facetiously claim is the antithesis to publishing for money—you’re aware that the reading community is so much more critical and culturally important than the profit you can squeeze out of Amazon. And yet that community is shunted aside by P&L sheets and BookScan numbers.

When I first got into this business there was a pride in that product that doesn’t seem nearly as present today. There are a few people who abide by the idea that they publish for the future and a belief in a vibrant book culture, but half of them are liars and the other half live in denial. “I know this won’t sell, but it’s important that readers have access to the ideas” is the most passé thing you can say nowadays.

Let me drag myself away from this weird form of career regret—everyone I grew up with, career-wise, is far, far more successful and talented than I am, and that’s not likely to change anytime before I die—to something about the field in general: it used to feel good to be involved in books. BookExpo America wasn’t some derided conference that “has no point” and is just a dumb waste when compared to the super-cool, super-exclusive, money-rules-the-day Winter Institute. Instead, BEA was a place everyone went because being around your colleagues added meaning to your bookish life. It was a morale boost that existed in a pocket universe away from the “bean counters” who we all used to hate, and now sort of abide by.

We’ve changed. Every idea is now radical, because publishing has lost its edge.

The real work of publishing will always be in challenging the status quo, but we’re all too afraid to debate each other, to create nuance among our leftist, liberal viewpoints. So instead we let capitalism win. And the radical ideas that would make publishing both fun and fair are outmoded and not analytical enough. Sell out fast and never think about how the game is completely rigged.

Leave a Reply