A Frozen Imagination

Over the course of the eleven years that Three Percent has existed, we’ve published approximately 300 posts about Iceland. We even held a special “Icelandic Week” when Iceland was Guest of Honor at the 2011 Frankfurt Book Fair. In addition to highlighting a ton of authors and musicians, we tried to record a Brennivín tasting that went way awry . . . Although at the time, I was totally into the worst hangover of my life because it was the middle of THE CARDINALS MIRACLE that included one of the most amazing World Series games of all time. (Sorry, I have to live in the past for a minute to get over the 2018 CARDINALS COLLAPSE. From an 80% chance to make the playoffs to 0% over six days? Cool. Reminds me of another incident in which the party with an 80% chance to win didn’t come through. Still too soon?) Open Letter has published six Icelandic books (out of our first 103 titles), with another coming out next summer. We are most definitely Iceland-obsessed.

According to a few different metrics, we were just ahead of the curve with the Iceland love. I first visited Iceland in 2006, when under 400,000 people visited a year. Nowadays, Iceland hosts over 2 million visitors annually—a 500% increase in just over a decade. That’s incredible.

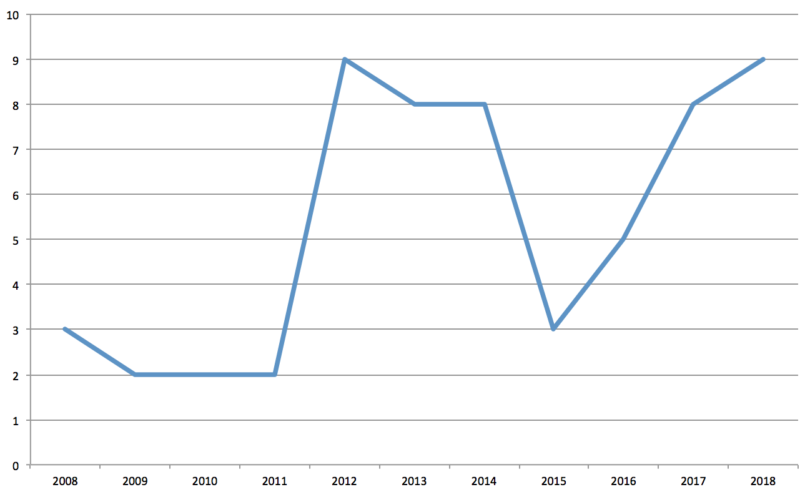

In 2008, we published our first Icelandic book (The Pets by Bragi Ólafsson), and only two other Icelandic books came out in English translation that year. Between 2012 and 2018, fifty translations of Icelandic fiction, poetry, and children’s books were published in America—an average of 7.1/year. Here’s a chart of the Icelandic translations over the history of the Translation Database.

What’s most interesting to me is the spike after Iceland was the Guest of Honor at Frankfurt. For ages, researchers like Rüdiger Wischenbart have been claiming that one of the few things that helps instigate translations of a particular country’s literature is being featured at the Frankfurt Book Fair, but it’s rare to get data that’s so clean and compelling. In the four years before being Guest of Honor, nine Icelandic titles were translated into English; twenty-five came out in the three years following the book fair.

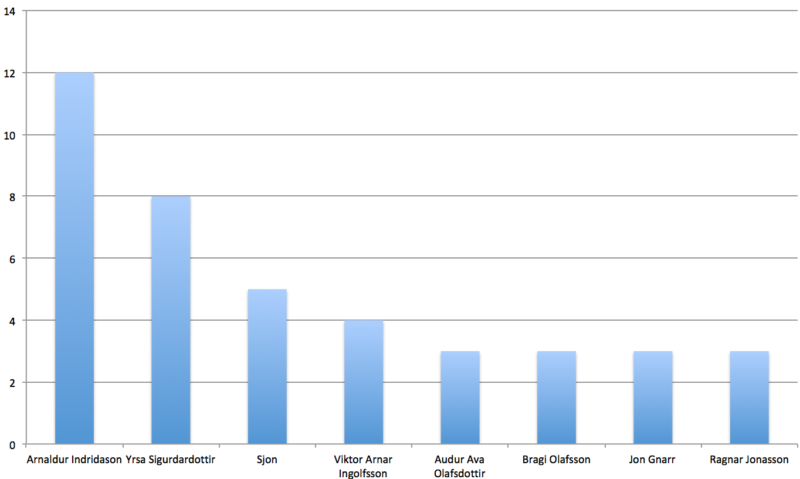

That said, a lot of these translations are coming from the same handful of authors. Of the fifty-nine Icelandic books in the Translation Database, forty-one (or 69%) are from eight authors, with the top three m0st-translated authors contributing twenty-five of those titles (or 42%).

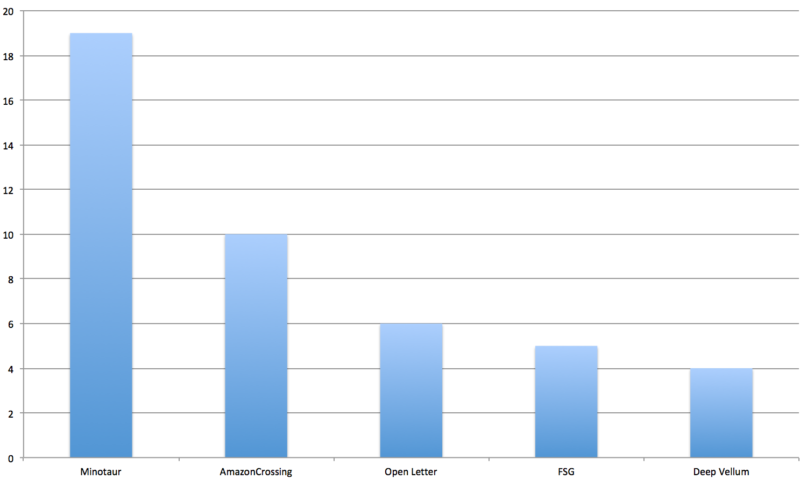

This sort of top-heavy concentration is also evident in the publishers who do the most Icelandic titles in translation. The top five publishers of Icelandic literature in America since 2008 have done forty-four of the fifty-nine titles, or 74.6% of the Icelandic books that have come out here.

Curiously, a commercial press tops this list, due solely to Arnaldur Indridason, Yrsa Sigurdardottir, and Ragnar Jonasson. After that, we have AmazonCrossing—who, in 2011, signed a deal at Frankfurt to do ten Icelandic books—followed by us, then FSG (entirely Sjón) and then Deep Vellum (mostly Jon Gnarr).

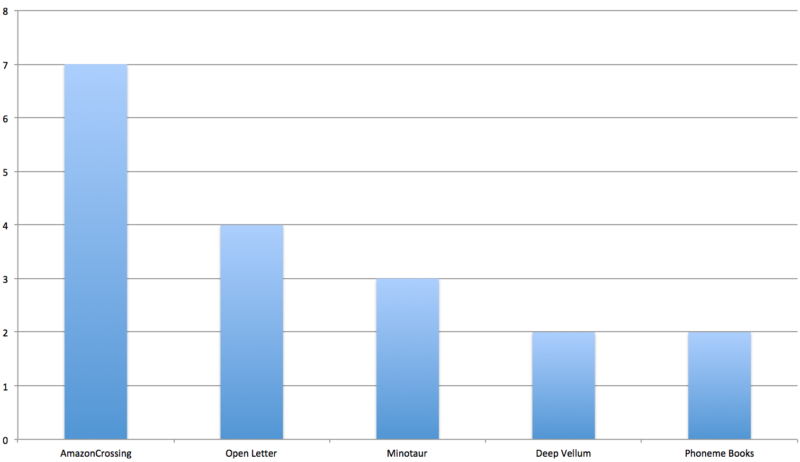

Here’s a chart of the number of different Icelandic authors published by the top five publishers of Icelandic literature.

Only thirty different Icelandic authors have been translated into English since 2008, and these five presses have done eighteen (60%) of them.

*

(It’s always rewarding to find out that you’re not the only person who makes silly mistakes.) (UPDATE: This has already been corrected, less than an hour after the post went live. Someone’s paying attention to these!)

CoDex 1962 by Sjón, translated from the Icelandic by Victoria Cribb (FSG)

For the first time in what feels like forever, I want to recommend a book to you. Wholeheartedly. Not “I liked this, not that,” or “the second half kind of blows,” or “it’s fine,” or any of my usual dismissive shit. I love this book. Straight up. It’s criminal that this isn’t on the National Book Award for Translation longlist. I’ll bet you $500 that it shows up on the Best Translated Book Award longlist. I’ll bet $100 it makes the BTBA shortlist. Then again, I understand the BTBA and not the NBAT, so . . .

*

Speaking of bets—and using bets to delay having to talk about a book—I want to follow up on something from my February 6, 2018 column (“column” sounds fancy):

Patrick Walsh of Custom Publishing Partners (hi, Patrick!) got drunk with a bunch of us on the last night. Several people—Nick Buzanski, Javier Ramirez, and Will Vanderhyden—heard him bet me $1,000 that in 2018, Hunter Pence will “have a Hall of Fame season” and bat over .320 for the year. Now, I’m not supporting gambling, but I’m taking that bet ALL DAY E’ER’ DAY. Right now Pence is projected to bat .264. To move from a lifetime batting average of .282 to over .320 basically impossible. Patrick, do you go to Fangraphs at all? I’M GOING TO TAKE YOUR MONEY THIS IS LEGALLY BINDING.

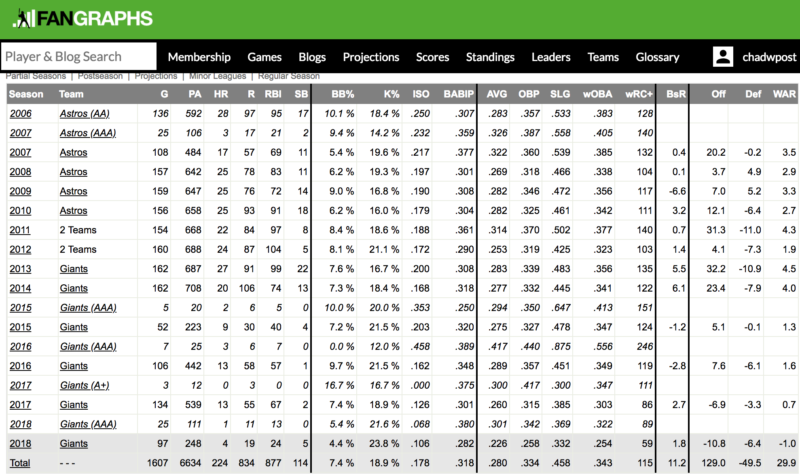

So, let’s go to Fangraphs and see what Hunter has been up to this year:

Oh NO. So, for the purposes of the bet, Hunter batted .226–not .320, not even the .264 that was projected. This is a lesson in saying “fuck hope! Embrace statistics!” and/or “don’t make drunken bets.” Whatever. But because I love baseball and am heart hurting over the aforementioned Cardinals Collapse of 2018, I’m going to dig a bit deeper. Of the 355 MLB batters with 200+ plate appearances, Hunter ranks 338th. Oof. His wRC+ (100 is AVERAGE) is 59! That’s tied with . . . Luis Valbuena and Carlos Asuaje (the fuck is that?) and Dixon Machado (????).

REAL INFORMED BET, WALSH. YOU CAN PAYPAL ME MY $1,000 NOW THANK YOU VERY MUCH.

*

Since everyone loves Bookstagram (that’s the right term, right?), here’s a picture of my galley of CoDex 1962 after finishing it.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a galley that transformed itself in such a weird way.

Let me tell one last digression before pretending that I can talk about books:

Last I got a text from NICK BUZANSKI, fan of the HATED SF Giants that was a screen cap of “Sean Carroll” telling him how they hoped the Cardinals missed the playoffs.

My copy of CoDex 1962 came with a really generous note from Sean McDonald of FSG who, for about ten hours, I conflated with Buzanski’s anti-Cardinals Sean Carroll. I very nearly sent the wrong Sean some weird baseball hate mail!

A whole set of jokes—about Seans, about Dodgers fans, about baseball nerds in baseball—was blown up by fact-checking my messages. Stupid facts ruining everything with their factness.

*

Sean McDonald? You can keep sending me these sweet, sweet Sjón books. I’ve known Sjón for almost a decade, read all his books, loved his imagination, and never believed he was capable of doing this.

CoDex 1962 is the Book of 2018. Here’s the list of 2018 translations I love (and can remember at midnight):

CoDex 1962 by Sjón

Fox by Dubravka Ugresic

The Bottom of the Sky by Rodrigo Fresán

Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes

Everything else is fine. Speaking of, it’s time for . . .

*

MY STRUGGLE CORNER!!!!!!!!!

Weekly update. I’ve read this much of Volume Six.

So I have about a day left!

I’m into the middle essay part about Celan (which was further proof that I prefer to read analyses of poetry than poetry itself) and about Hitler (which is really fascinating), but what’s been most interesting about this section is how the audiobook reader—Edoardo Ballerini—is the voice I hear when I read Knausgaard.

This is a natural result of having listened to multiple volumes of My Struggle, all read by Ballerini, but it’s still strange to hear such a specific voice when book–reading the book. (I am going back and forth—listening on the way into the office, reading in the evening.) His rhythms, the way he pronounces words (like “prawns,” so many repetitions of the word “prawns” in this book), and his idiosyncratic pauses are all showing up in my mind now, and altering the pace of my reading.

*

There are so many reasons why you should read CoDex 1962, from the reference to Gudbergur Bergsson (our author!) to the almost Pynchon-esque madcap ending to the second part, to the incredible structural twist that’s revealed in the final section and the epilogue. I don’t want to give away too much of this book—it’s a slow build, and one that should be savored bit by bit—but I want to at least point out a few interesting things about each of the three parts of the trilogy.

This is the sort of novel that starts from a pretty simple point—Jósef Loewe is telling a researcher the story of his life—but blossoms outward with story after story, thread after thread, running rampant through various genres and styles, combining and recombining in ways that are both incredibly stimulating and fun, while challenging the reader to hold on to all these ideas.

I’m a sucker for this sort of novel. Overstuffed. Reliant on a tricksy structure. A plot that advances through point-of-view shifts that modify everything you thought you had figured out.

How complicated is the plot? Well, if you don’t want anything at all spoiled, skip this next super-long quote. If you want a bit of motivation to see just how wild and wooly this book gets, then enjoy:

The story he had told her—as far as she could grasp its thread—was of how the Jewish alchemist Leo Loewe, his father, had come to Iceland with the Godafoss at the end of the Second World War, having escaped from a Nazi concentration camp, more dead than alive, with the sole possession he had managed to rescue from the disaster, a hatbox containing the light of his life, the figure of a baby boy moulded from cold clay, which turned out to be Jósef himself—shaped, according to his father, by the hands of his “mother,” the kindly, talkative chambermaid Marie-Sophie X, while she was nursing him, a broken-armed fugitive, for the few days he had spent hidden in a secret compartment between the rooms of the Gasthof Vrieslander in the small town of Kükenstadt in Lower Saxony, the act of creation reaching its climax when the child opened his eyes and saw the girl see the fact, before which two frames of film had been placed in his eye sockets, one showing the Führer in full rant, the other showing him surprised at having spilt gravy down his tie—yes, Jósef, who’d had to wait twenty-one years, moistened and massaged with goat’s milk every day, to be wakened to life, until finally Leo, aided by his two assistants, the Soviet spy Mikhail Pushkin and the American theologian and wrestler Anthony Theophrastus Athanius Brown, after pursuing the twin brothers Már C. and Hrafn W. Helgason (Freemason, champion athlete, stamp collector, parliamentary attendant, and former deckhand with the Icelandic Steam Ship Company), had succeeded in recovering from the wisdom tooth of Már, or rather Hrafn (who in the heat of the moment had turned into a werewolf), the gold filling made from the ring the brothers had stolen from Leo long ago on the voyage to Iceland, which was essential for making the magic seal that he then pressed into the clay between the boy’s solar plexus and pubic bone, in place of a navel, wakening him to life on the morning of Monday, 27 August in the oft-mentioned year.

This lengthy speech had been Jósef Loewe’s response to the first four questions on the form:

a) Name:

b) Date of birth:

c) Place of birth:

d) Parents (origin/education/occupation):

And there’s so much more that could be included! Such as the first woman born in 1962 made up of four different sets of DNA from four different men. Or the role that the angel Gabriel plays in Jósef’s story. Or any one of the numerous digressions that are sprinkled throughout this mock-epic.

*

I want to include this here, since it is a striking cover, simple, yet layered. And it’s been out there on the Internet for months—just not on FSG’s own site for some odd reason.

Not going to go too deep into my reading of this book—it’s a complicated piece of literature, and Sjón’s books open themselves up beautifully to multiple readings—but there is a set of connections about the creation of a new sort of man. One that can interact with the biomass and the larger scope of life without destroying it. This impulse is offset by the main focus of the book: all the Icelanders born in 1962 who have mutated due to exposure to radiation and their eventual deaths. It’s a book that places a huge weight–and huge word count—on the creation of a single life (a la Tristram Shandy), yet ends with the annihilation of humankind.

All of this results in an interesting asymmetry of time in the book, with two-thirds of the book focused on the past before bolting off into the distant future, blowing up the scope of this novel in an intriguing way that also raises some questions about the overall value of a single life’s story.

*

Last thing: I like Victoria Cribb’s translations of Sjón. She’s done all of his books, which doesn’t always happen, but seems like it would be an advantage when working with authors who tend toward the strange and experimental.

Which reminds me of one thing I left out of my last post, but wanted to mention:

At the end of my sob story about the NBA longlist for Translation, I summarily dismissed Don’t Send Flowers by Martín Solares. I’m definitely not reneging on that—the book is pretty forgettable—but this is an instance where I feel very secure in criticizing the text and not the translator.

My big problem with this book was how lacking in style it is. It’s flat as can be, totally uninspired, workmanlike writing.

At random:

The first punch broke the detective’s nose. I’ve got you now, asshole, thought the Bus. The second punch left Treviño blinking like someone suddenly roused from a deep sleep. The third opened a gash above his eye.

Anyway, Heather Cleary also translated the recently-released Comemadre, which does have a unique, compelling, strange style. She can translate complex, beautiful prose. So all the clunkiness in Don’t Send Flowers? I’m willing to bet that’s on Solares.

On an algorithmic level, one could contrast word usage statistics from the original author against those of the translator. Is a phrase more common in one than the other? Does the reading level shift from one language to another? Are there tags that author T or translator B use over and over?

But in the end, if you read enough translations, you can sense these things. Heather is great. I’m sure a lot of people will enjoy the Solares, but it’s probably more for the plot and to learn about Mexican corruption than for his particular voice.

[…] and wonders about adding this to the Translation Database. He also has some curious info about Icelandic books in translation and then promotes one of his favorite books of 2018. As can be expected, things take a turn when […]

[…] A Frozen Imagination […]