Why Are Patreon [Time for a Basque Rundown]

I promise I’ll be back on schedule soon—this computer situation is really taking it’s toll . . . I’m currently writing on my iPad, using a Bluetooth keyboard and feeling like a gross millennial working out of a third-wave coffee shop, saying NO! to Large Computer, and proving that Jobs is Genius and that 2019 is about working nomadically.

I’m living that shitty Microsoft Surface ad for cupcakes.

As much as I’m not totally comfortable writing this way, after writing about Castilian, Catalan, and Galician books from Spain, I definitely can not skip out on a Basque post. Plus, I have so many interesting supplementary books to include . . . which I haven’t actually had a chance to read . . . but . . . well. Let’s just get into it.

*

Later today we’ll post an interview with Basque translator Amaia Gabantxo, whose most recent translation is Twist by Harkaitz Cano (more about him, and his books, below), which will really get into the nature of Basque literature, translation, and more. So, in preparation for that, I’ll just try and provide some sort of frame . . . Call it, “Seven Random Facts about Basque Literature That Every Spaniard Will Recognize” in honor of the recent BuzzFeed firings. (Too soon? Oh, c’mon. Sure, I feel bad for anyone who lost their job, but BuzzFeed is one of the first new media joints to fuck the world. All this bad publicity for them is like catnip for my soul. THIS IS KARMA. Like, you know, when someone steals your bag and computer and passport because you’re like, grumpy on Twitter. I DON’T UNDERSTAND IRONY.)

This is usually where I insert a very low-level chart related to Basque literature. That would be nice, but there are only 10 titles translated from Basque in the Translation Database total, and only 5 if you restrict it to fiction. Two from Archipelago (Twist and Plants Don’t Drink Coffee), two from Center for Basque Studies (Blade of Glass and Two Basque Stories), and one from Hispabooks (Martutene). There would be more, but the Axtaga titles Graywolf have done are translated from the Spanish/Castilian. (And the data from the Center for Basque Studies Press is incomplete. They don’t have translators listed on iPage or Amazon, so I have to dig through every book one-by-one.)

That’s not great!

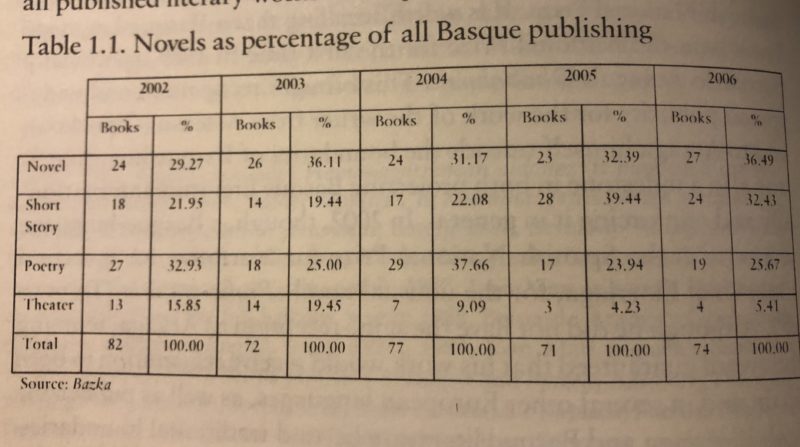

And instead of a low-key chart, this time you get a really janky photo:

I’m not going to pull some wizard SABR shit out about this chart—I just want to point out that in 2006, there were 27 Basque novels published. And, sure, 24 short story collections. And 19 collections of poetry. A total of 74 books when you count the 4 works of theater as well. 74. That’s one new book every 4.8108 days. I’m 60% sure there’s a book published in America every 4.8108 seconds.

That chart comes from Contemporary Basque Literature edited by Jon Kortazar, a seemingly comprehensive breakdown of Basque literature, with chapters on the novel, Basque poetry, short stories, YA and children’s literature, drama, and the contemporary Basque essay. If you are at all interested in learning about what’s going on in the northeast of Spain

you should totally check it out.

It doesn’t make a lot of sense to summarize a summary, but there are a couple exportable things that will help frame Basque literature as a whole.

First off is Jon Kortazar’s description of the evolution of the modern Basque novel. What interests me about this is how universal it seems. Irate Retolaza and Ibon Egana (authors of “The Contemporary Basque Novel” section of this book) mark 1957 as the start of the modern era. And then, handing the aesthetic baton to Kortazar:

* Modern Prose

* The existential novel (Txillardegi)

* The new novel (Saizarbitoria)

* From allegory to symbol (Arantxa Urretabizkaia, Mikel Zarate, Anjel Lertxundi, and Jose Austin Arrieta)

* Bernardo Atxaga’s narrative

* Literature in the 1980s: Narrative (Joan Mari Irigoien, Pako Aristi, and Juan Luis Zabala)

* From the 1990s to 2000 (Pako Aristi, Aingeru Epaltza, Joxemari Iturralde, Edorta Jimenez, Xavier Mendiguren, Jon Arretxe, Yolanda Arrieta, Harkaitz Cano, Andoni Egana, Xabier Montoya, and Lourdes Onederra)

Having read only two of these authors, I don’t have any way of reasonably analyzing these groupings, but the idea that literature goes from Modernism (Joyce) to Existentialism (Camus), then the New Novel (Robbe-Grillet), then Symbolism (blanking) to Narrative (Carver?), to 1980s narrative (??—cocaine and McInerney?), to 1990-2000 (maybe the sincere postmodern moment?) seems to track.

Depending on what any of those terms mean in a Basque context.

Again, I have no idea, but there is a tendency to try and map these movements onto the trends in world literature I am familiar with . . . Even if within every one of Kortazar’s groupings, there are huge departures and notable variances.

*

Another interesting part of this same essay is the “Tendencies in the Modern Basque Novel” section, which, again, I’m not going to go into detail with—in part because only a few of the referenced books are available in English, so . . . —but instead will list each of the “tendencies” so that we can all guess at what’s behind the various doors:

* Characters’ Subjectivity or Readiness to Imitate Consciousness

“An attempt to get close to the conflicted internal world of a character.”

Sounds familiar. And classic twentieth century. Great books for NYRB perhaps?

* Subjectivity and Sociopolitical Conflicts in the Twenty-First Century Basque Novel

“Novel writing that examines characters’ internal situations and internal conflicts has also been productive during the last decade, even though it has often remained separate from the canon and main literary tendencies.”

Political novels from the Basque Country? Sign me up.

* The Gay, Lesbian, and Transsexual Basque Novel

“Few Basque writers have placed gay, lesbian, or transsexual subjectivity at the center of their novel writing, and those that have done so are latecomers.”

No matter how late, no matter how few, these books need to be made available.

* Fantastic Realism

“The first hint of Latin American influence was apparent in the allegorical novels of the early 1970s.”

I believe this is about where the Big Five step in. We don’t know of Basque, but we recognize these tropes!

Oh damn. One of the books listed in this section is Atxaga’s Obabakoak—the first Basque novel I ever came across. Originally published by Penguin.

* Allegorical Novels

“When discussing Txillargedi’s novel Elsa Scheelen (1969), we recalled his thoughts in one interview in which it was highlighted that at that time realist novels were not very successful while there was a tendency toward magic realism. Moreover, as noted in the previous section, between 1969 and 1976 Saizarbitoria’s nouveau Roman or new novel also started a dominant trend, bringing with it a break with traditional storytelling methods. [. . .] For that reason and the growth in experimental novels during the 1970s the Basque novel turned in another direction. Many interpretations of novels written in the early 1970s leaned toward the allegorical or symbolic.”

I love that the New Novel is referenced here (didn’t realize that when writing the bit above), and am intrigued—in general—by writing in the 1970s. This is a post for another day (and/or conversation with me at a bar), but in my naive understanding of world history, I feel like the 1970s were the last time anything was possible. The world felt a bit in balance and art (and society) could careen outward into weird dimensions and forms and strange showings meant for only a few, or it could become Raymond Carver and a consolidated corporate monolithic culture of bestsellers. Damn. We should never have taken that Reagan path.

* Realist Novels

“The early manifestations of realist Basque novels created a sense of mistrust among many devotees of literature. These stories situated close to reality were typically linked with some specific ideologies, without taking note of the discursive models devised in order to tell the stories. But the ideologies represented in literature is not just the result of the topic chosen in order to create a fictional universe. Often the ideology of a novel owes more to the way of telling a story than to the story itself.”

I’m intrigued by this, although I’m curious what the “ways to tell a story” might be in the Basque world. It’s the sort of truism that can apply to a very wide range of writing styles. It’s what we look for in choosing books for Open Letter though . . . So many agents pitch content, but that only goes so far. It’s the form and the style that makes a book work or not. (Another truism.)

* The Twentieth-Century Wars and History

“Outside the context of the Basque Country, Basque novel writing in recent years has factionalized the most terrible events of the twentieth century (war, totalitarianism, and so on).”

This is Twist. Also, for better or worse, this is probably the category of books that are most likely to make their way into English. We’re soooo into conflict and violence.

Wait. Another truism: We prefer violence to literary form. Ugh. I hate this reality sometimes.

* Other Realist Approaches

“There are other writers whose work, while being part of the realist tendency as well, remains outside the main trends followed and themes examined, and that has taken its own direction.”

Say more!

Pelli Lizarralde, for example, has developed a specialized esthetic that pays particular attention to those nearby; an esthetic that owes a lot to both American narrative (above all to Cormac McCarthy) and the influence of movies. His is a literature given to describing atmospheres rather than major events . . .

It goes on for a bit, but mostly sounds like the French Minimalism that Warren Motte has written about (Oster, Chevillard, Toussaint). That . . . That would be intriguing.

* Genre Novels

Sorry, Rachel Cordasco, but they don’t list speculative fiction at all.

And only one erotic novelist?

* The Basque Novel and Metaliterature

SAY NO MORE.

In recent decades novel writing that does not emphasize fiction and narration has tended more toward a metaliterature that places the writer and the quality of being a writer at the center of its fiction.

Always interesting to me (and Dalkey Archive).

When is the Basque Country going to be the guest of honor at Frankfurt or LBF?

*

Let’s take a break! (This is like the good ol’ days when I wrote 9,000-word essays that never ever ended, yet had intermissions filled with irrelevant jokes and schizoid voices and whatnot.)

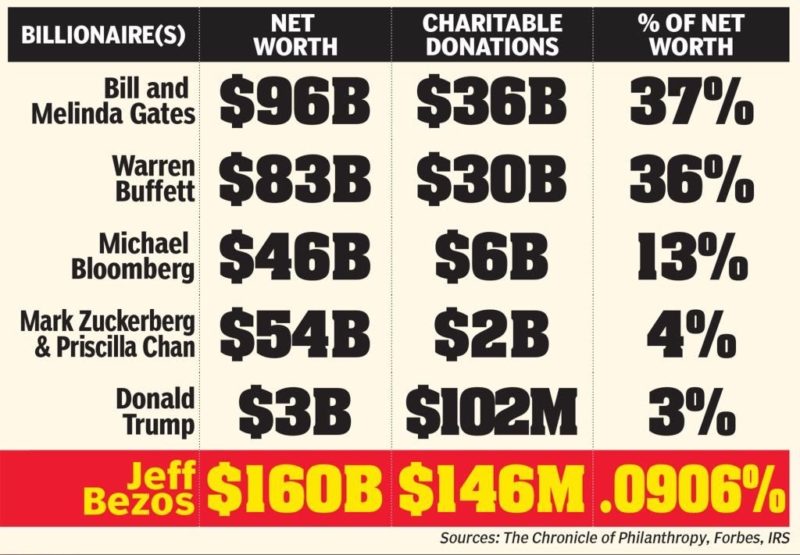

I’m sure you’ve all seen this:

You’ve all seen it, you all agree it’s wicked fucked up, and y’all know the Best Translated Book Awards are funded by Amazon. Let’s leave Bezos behind for a moment and talk about cultural funding as a whole.

Does anyone have data on how cultural products are funded in 2019? Not just nonprofit presses, museums, and the NEA, but things like podcasts, various artistic websites, and other individual artistic projects (graphic novels, performances, public sculptures, etc.).

I have a gut feeling that, after governmental funding and a handful of large foundations, Patreon and Kickstarter are right there as major organizations conveying money to creative endeavors. Probably a billionaire or two (maybe? who?) but a significant chunk of funding for arts is coming from . . . each other. Patreons instead of patrons.

I’m 60%+ positive I’ve referenced this study here before, but a few years back I heard a report on NPR about how the top 100 philanthropists in America had more or less stopped donating to the arts. All the new Silicon Valley Millionaires didn’t give a dime, and the older generation that did was very quickly out-percentaged. (Not a phrase, but you know what I mean.)

This was very disheartening at the time. As an organization whose long-term viability lives or dies by the aspiration of “angel donors,” the general disinterest to funding the arts is disturbing. Especially because 175% of Silicon Valley “philanthropists” donate to companies like Theranos who are developing magic water so that Tom Brady can ruin football till I’m 90 and Peter Thiel can live long enough that his brain grows wires. Fuck all that.

Given the general disinterest among the super wealthy (who used to be simply “rich,” when I was growing up, four decades ago, but whose capital is now so astronomical that we don’t have the language to properly talk about the widening wealth gap in the world) to fund arts and culture, and the erosion of state and national funding agencies, the only way to be able to produce things is to have your friends Patreon it.

When you stop to think about it, that’s not the best system.

Let’s stick with podcasts to make this point: I listen to a lot of them! Approximately 900% exist thanks to sponsorships from Hello Fresh and Harry’s and Quip and Me Undies and Stamps.com, but the other 200,000,000? Patreon supporters.

If you’re not already aware of Patreon, here’s a short description: It’s a site where you can pledge $X a month to podcasts or writers or websites or whatever that you like. Cool, cool. These places need money. And if you like something that you’re getting for free? Giving them a bit of coin is only fair. But not necessarily when you hold this up to the larger system of wealth and payments that it’s embedded within.

The problem I have with this “new economy” of microtransactions among friends, is that WE DON’T HAVE ANY MONEY. The more you dig in, the more it feels like a racket . . . Every middle-class person is giving every other middle-class person $5/month to buy better microphones from a company that grossed several MILLION last year. We all stay poor helping one another pursue our intellectual hobbies and the corporations and UBER-WEALTHY make bank. How is this a good system?

This is a tricky thing to quantify, statistically, but given that most all federal workers are living paycheck-to-paycheck, it’s pretty fucked that they would be supporting the podcasts that keep them human on the 45-minute soul-sucking subway to work when so many billionaires could give away another billion dollars without noticing and fund 100% of all podcasts made this year.

Or, to bring this back home: If 10 philanthropists donated a million a year to support book publishing—presses that expand societal consciousness by publishing international voices and nonfiction and other necessary news that isn’t going to necessarily work in the marketplace—they would change the landscape forever.

Ten million dollars a year is NOTHING to ten of the U.S.’s richest. But instead, everyone doing good work has to hustle on Patreon and Kickstarter for $10/month donations to pay for server space. (Which, again, could be gifted in certain circumstances—socially aware podcasts, any podcast dealing with gender and discrimination—but instead, the not-well-off give the not-well-off money to give to The Man. And feel good about it, since there’s so much traffic on their Patreon page! Worst. Possible. Reality.)

*

Twist and Blade of Light both by Harakaitz Cano, and both translated from the Basque by Amaia Gabantxo (Archipelago Books; Center for Basque Studies Press)

Given how long this post is, I’m going to keep this section incredibly short, but promise to get back into more book analysis and whatnot next week.

When I told Amaia I wanted to interview her and have her speak to my class about Twist, she STRONGLY encouraged me to pick up Blade of Light as well, in part because it’s much shorter (95 pages compared to 519) and is a somewhat funny alternate history in which Hitler won WWII and decided to take over America. That’s not the funny part. The funny part is that he’s obsessed with torturing Charles Chaplin for The Great Dictator.

After you read the section below, this will make even more sense, but Blade of Light is Cano’s outward looking, non-nationalist, universalist book. Especially in contrast to Twist, which is long, all about the Basque situation of the ETA (Basque nationalist terrorist organization) and GAL (Spanish government death squads who tortured and killed ETA members), and is very inward focused, probing the national question, and requiring uninformed readers to do a bit of work.

I really enjoy both titles, and am glad that I’m using Twist in my class, since it brings up a lot of interesting questions about why we read international literature, what expectations the author and translator can have of readers, and the issue of universal vs. regional works. But it would be interesting to survey a wide range of English readers and see which book they preferred. Given the reach of the two publishing houses behind these books, sales don’t accurately address this question. I think we can all make assumptions, but it would be curious to parse the data and see what trends and biases and interests you could find.

*

The other book on Basque literature that I got through interlibrary loan for this post is This Strange and Powerful Language by Iban Zaldua, translated from the Basque by Mariann Vaczi. What intrigued me most about this was actually its subtitle: “Eleven Crucial Decisions a Basque Writer Is Obliged to Face.”

Similar to above, I didn’t have a chance to read this book in full, so I’m just going to quote Zaldua’s eleven decisions, since these main points articulate a really interesting position for Basque writers. So, here goes:

1) “The first decision that a Basque writer has to make concerns language, of course: they have to choose between Spanish or Basque—or between French and Basque . . .”

Obvious enough, although this clearly will have serious ramifications with regard to potential readership.

2) “Another question that all Basque-language authors have to face during their careers is whether their attitudes to their literature, their language, and in general to the world, will be agonic or not. Needless to say, agony is the most habitual disposition: if we can universally define the writers as an animal that complains, the Basque writer represents the highest stage of the evolutionary chain.”

I am totally digging Zaldua’s voice, although, I have to wonder how many Eastern European writers he’s met . . .

3) “A Basque writer will also have to decide if he or she will be a nationalist writer or a non-nationalist one.”

It’s not exactly the same, but Catalan writers have to make this choice as well. It’s a crucial decision to make, and one that comes under a lot of scrutiny in regions like these.

4) “. . . a Basque writer will have to consider if they should become a ‘politically committed’ writer or not.”

Very much tied to decision 3.

5) “Basque writers [. . .] must choose whether to write about the ‘Basque conflict’—or, as I call it with my inner circle, The Thing—or not write about it.”

Yep.

6) “Another question is whether The Thing should be the hallmark of Basque literature [. . .] or rather that we should forget about it in order to be able to triumph in the Global Republic of Letters.”

This sort of “regional vs. universal” debate crops up all over the world, even in widely spoken languages (see: writers deciding to write in Hindi or English), but it’s especially critical for a place like the Basque Country. To leave behind The Thing in order to court a larger readership? Feels a bit like a betrayal. Then again, if you can’t get the outside world to read/learn about The Thing unless you get into the Global Republic of Letters . . .

7) “Once the hour of embarking on the conquest of the Global Republic of Letters arrives, one has to make a decision about whether to have a stopover in Spanish, or to bypass it.”

This seems to relate a bit to the number of professional translators from Basque there are. Going from Basque to English directly (and entering the Global Republic of Letters) seems preferable? Although, if your book is translated into Spanish first—and maybe translated out of Spanish to the rest of the world . . . Those seem like better odds.

8) After an interlude about relay translations (from Basque to English, then English to Hungarian, etc.), he turns to authors who decide to write in Spanish initially, leading them to have to decide “during his or her career whether to complain bitterly—or not—about the (supposed) discrimination to which he or she is subjected for not writing in Basque.”

9) Going back to writers writing exclusively in Basque, “another dilemma Basque-language writers tacitly face is whether they should—or should not—lean on their literary tradition, on the tradition of literature in Basque, when it comes to building their corpus.”

Given the fact that there were 27 Basque novels published in 2006, I can understand the concern.

10) “The Basque writer will also have to deliberate on a tenth decision: he or she can decide to be an ironic writer or not. Or can they?”

I’m going to read this whole book. The more I’m skimming and dipping in, the more intriguing it is, both in defining the position of someone writing in Basque, and of describing the overall landscape of modern and contemporary Basque literature.

11) “And finally, when writing a book, a Basque writer has to decide whether he or she will emphasize their indigenous exoticism, or whether they present themselves as a writer of an ‘universal’ spirit.”

And there we have it! Phew. Longest post of 2019! (Although Amaia’s interview will beat this . . . Slightly.)

Final note: If you’re interested in any of this, go to the Center for Basque Studies Press. They have so many interesting titles, and are the source for info on the Basque Country.

Leave a Reply