Interview with Peter McCambridge of QC Fiction

Following up on Monday’s post, here’s an interview with the founder of QC Fiction, Peter McCambridge. Since he goes into most of his bio below, I’m not going to preface this all that much, except to congratulate him on being a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for Translation and the Giller Prize for Songs for the Cold of Heart, his translation of La Fiancée américaine by Eric Dupont.

Also, come back later for an excerpt from Prague by Maude Veilleux, and translated from the French by Aleshia Jensen & Aimee Wall, and forthcoming from QC Fiction in June 2019.

We’ve shared a few pints in the pub before, and corresponded a bit, but for everyone else reading this, could you introduce yourself and explain a bit of how you came to live in Quebec City, translating massive Quebecois books and running QC Fiction?

We’ve shared a few pints in the pub before, and corresponded a bit, but for everyone else reading this, could you introduce yourself and explain a bit of how you came to live in Quebec City, translating massive Quebecois books and running QC Fiction?

So maybe it’s best if everyone else begins by imagining me talking about Quebec literature in an Irish accent. I’m from close to Belfast originally (which explains the accent). I studied French and German literature at Cambridge University and then moved to Quebec City (just because it’s a lovely place to live and I wanted to live my life in French) in 2003.

To be very honest, I think I got into Quebec literature because I didn’t know much about it and had no idea that it had a reputation, at the time, for being not particularly good. There were obviously a few big writers (who I didn’t know of yet) but I had none of the preconceptions a Canadian might have had. I hadn’t been forced to read dry Quebec writers in academic translations at school. I had no idea who any of these people were. I could just walk into a bookstore and pick up anyone at all. It was a whole new world.

Luckily for me, the first book I picked up happened to be Bestiaire by Eric Dupont. I absolutely loved it. You can tell a lot about the tone by the cover.

There’s something so blissful and quirky about the writing that I just love. I was working as an in-house translator at the time and reading Eric Dupont made me want to drop everything and start translating Quebec literature instead. I pitched and pitched it and no one was interested. So instead I pitched other books and began translating fairly regularly for Baraka Books, a small press in Montreal that focuses on history and politics with an accent on Québec.

There’s something so blissful and quirky about the writing that I just love. I was working as an in-house translator at the time and reading Eric Dupont made me want to drop everything and start translating Quebec literature instead. I pitched and pitched it and no one was interested. So instead I pitched other books and began translating fairly regularly for Baraka Books, a small press in Montreal that focuses on history and politics with an accent on Québec.

What was your motivation behind starting QC Fiction?

Whenever I translated fiction for Baraka, there was always a link to Quebec and its history. The books were good, but none of them ever really took off. After a few years of this, I approached the publisher Robin Philpot and said, “Look, why don’t we start an imprint? I’ll run it for you and we’ll just translate and publish the best books we can get. It doesn’t need to be historical fiction or tied to Quebec in some way. We’ll just do young, up-and-coming writers from Quebec who have something to say.”

Eric Dupont and Bestiaire (which I translated as Life in the Court of Matane) seemed the natural place to start.

Since I always get this question, I’m going to throw it back at you: What type of books does QC Fiction want to publish?

We’ve just started our fourth year of publishing and it feels as though people are starting to pay more attention to what we’re doing, which is great. Right from the start, we’ve been trying hard to do things differently. This has meant giving a chance to young translators, most of whom have never been published before. Most of our books are first novels. And more than anything, I aim to publish idiomatic, readable translations for the international market.

For too long, much of Quebec literature was translated by the same two to three people. This is starting to change, and I’m happy to be playing a small part in bringing about that change.

As a reader, I want a story. So QC Fiction tries to publish storytellers, although obviously we’re after really great writing as well. But we’re not experimental. I want a good story, well told, and then I ask a young translator to take their time and make a great job of it. We then spend a long time working through the translation together, polishing it, asking the author plenty of questions. From start to finish, our translation philosophy is: what would the writer have put had they been writing in English? How would this sound naturally?

How would you judge your first three years of publishing?

How would you judge your first three years of publishing?

Honestly? I don’t know. There are definitely ups and downs. There are days when I feel disillusioned with the whole thing and other times when I feel like I have the best job in the world. Every time I go to a book fair, I have this overriding sense that I’m in the right place, where I should be, with likeminded people. We’re all in it together. For me, there’s nothing more important than culture, and I’m genuinely happy to be working in culture.

Songs for the Cold of Heart, one of my translations for QC Fiction, was a finalist for the Giller Prize last fall. The Giller Prize is absolutely huge in Canada. It’s basically our Man Booker. The award ceremony is broadcast live on national TV, there are interviews everywhere, they flew us to events in New York and England . . . it was massive, particularly for a tiny press like us. Being one of the five finalists was a game-changer. There’s been real interest in Songs for the Cold of Heart from international publishers, I think sales were upwards of 6,000 copies in Canada by the end of 2018. It’s been huge. It’s been great.

And then there are days when I wonder what would have happened if we hadn’t been lucky enough to be shortlisted for such a huge prize. The book would have just disappeared. No one would have talked about it, hardly anyone would have reviewed it, and we would have lost money on a great book and perhaps compromised the future of QC Fiction. It wouldn’t have gotten all this praise. And that would have been so disheartening for what is such a good book. (Like any novel, it’s not for everyone, but I think it’s a good book!) So on good days I’m grateful for what was such a fun, once-in-a-lifetime experience. And on bad days, I wonder just how dependent on prizes (and luck) we all are in order for a book to sell and be deemed a success.

In a broader perspective—and for the benefit of readers like me, who don’t know a ton about Quebecois writing—are there any general trends, or particular movements, or ages, in Quebecois literature? Who are the handful of writers we should be reading?

These are questions I try my best to answer at my blog, Québec Reads. We’ve been publishing weekly interviews, excerpts, and reviews of books (which often haven’t been translated into English yet) for coming up on five years now. We try to take a close look at the nuts and bolts of the translation process. We ask booksellers and authors and translators what they’re reading. What makes a book from Quebec a book from Quebec?

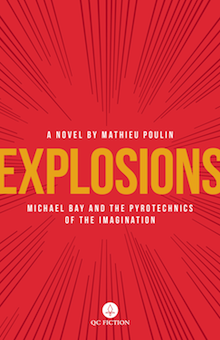

As everyone is keen to point out to me, there are no hard and fast answers. Very quickly, what I would say is that Quebec literature (like Quebecers themselves) likes to take chances. There is very little respect for norms and authority. There’s obviously a broad spectrum of writers and writing out there, but a lot of what’s published in French is irreverent and slangy and largely untranslated. The more serious, literary writers tend to make it over into English and this is another thing I’m trying to redress with QC Fiction, with books like Behind the Eyes We Meet (whose tone flirts with chick lit at times, before becoming something very different) or Explosions, a mockumentary-style, fictional biography of Michael Bay, or our next book, In the End They Told Them All to Get Lost, which belongs to this tradition of writing that doesn’t take itself too seriously, but nevertheless has plenty of interesting things to say.

As everyone is keen to point out to me, there are no hard and fast answers. Very quickly, what I would say is that Quebec literature (like Quebecers themselves) likes to take chances. There is very little respect for norms and authority. There’s obviously a broad spectrum of writers and writing out there, but a lot of what’s published in French is irreverent and slangy and largely untranslated. The more serious, literary writers tend to make it over into English and this is another thing I’m trying to redress with QC Fiction, with books like Behind the Eyes We Meet (whose tone flirts with chick lit at times, before becoming something very different) or Explosions, a mockumentary-style, fictional biography of Michael Bay, or our next book, In the End They Told Them All to Get Lost, which belongs to this tradition of writing that doesn’t take itself too seriously, but nevertheless has plenty of interesting things to say.

We’re in a bit of a golden age for Quebec literature. We’re fortunate to have writers like Eric Dupont, Christian Guay-Poliquin, Catherine Leroux, and Daniel Grenier being published by quality presses, in French and in English.

There is a lot of interest in Quebec literature at the moment. As you pointed out here a couple of weeks ago, the number of translations from Quebec doubled between 2015 and 2016. What remains to be seen is whether this interest is sustainable, whether it is reflected in growing interest in Quebec writers, or whether it will turn out to be something of a bubble and publishing houses in the rest of Canada, and around the world, will be paying less attention to Quebec writers ten or fifteen years from now.

Leave a Reply