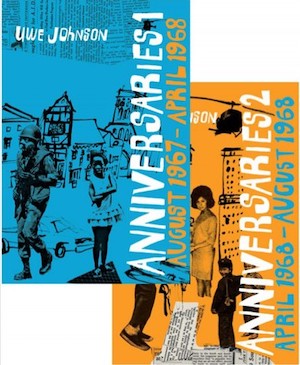

Blogging Like It’s 1967 [Anniversaries, Volume 1]

Tomorrow afternoon we’ll run the first of several interviews with Damion Searls, translator of the first complete version of Anniversaries to appear in English. If things go according to plan, each month we’ll dig deeper and deeper into this massive book, a twentieth-century masterpiece that weighs something like five lbs.

(Quick sidenote: It’s quite likely that the three volumes of Fresán’s trilogy—The Invented Part, The Dreamed Part, and The Remembered Part—will weigh slightly more. Obviously this is now a contest. Forget covers, we should judge books by the ounce! GIVE ME FOUR POUNDS OF PYNCHON AND A HALF POUND OF LISPECTOR, THANKYOUVERYMUCH.)

But seriously, this publication is a literary event for that small group of readers (10,000?) who get excited by the idea of literary events that are unabashedly ambitious in an Old European sort of way. This sort of publishing project doesn’t happen that often anymore. Sure, there have been retranslations of Russian classics over the past decade (War and Peace is the first that comes to mind), but those books are already known by the general public (in contrast to the “reading public” or the “literary public”) and have a built-in network of support. You have to review the “definitive” Don Quixote, and given that the book is already taught in universities across the country, there’s a natural landing place for a significant number of copies. If nothing else, critics and scholars will buy the new edition to compare against the existing ones—which will remain available, and will still have their loyal defenders who prefer an early translation for one set of reasons or a simple case of familiarity and nostalgia.

But seriously, this publication is a literary event for that small group of readers (10,000?) who get excited by the idea of literary events that are unabashedly ambitious in an Old European sort of way. This sort of publishing project doesn’t happen that often anymore. Sure, there have been retranslations of Russian classics over the past decade (War and Peace is the first that comes to mind), but those books are already known by the general public (in contrast to the “reading public” or the “literary public”) and have a built-in network of support. You have to review the “definitive” Don Quixote, and given that the book is already taught in universities across the country, there’s a natural landing place for a significant number of copies. If nothing else, critics and scholars will buy the new edition to compare against the existing ones—which will remain available, and will still have their loyal defenders who prefer an early translation for one set of reasons or a simple case of familiarity and nostalgia.

That’s not really the case here, though. Most people don’t know of Uwe Johnson. Granted, he was published by major presses . . . back in the 1970s. The abridged version of Anniversaries has been out of print for more years than my students have walked the earth. (Significantly more?) And, as Edwin Frank mentioned during our discussion, there’s not a whole lot of critical materials out there on Johnson or this book.

And yet, the publication of these two volumes (in a very attractive slipcase set, which, with the forthcoming publication of Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Nocilla Trilogy, seems to be “all the rage”) is an event. Again, not for everyone, or at least not in the way that a new Harry Potter book was an EVENT, but definitely an event.

From the Publishers Weekly piece on its publication:

“This is recognized in Germany as a book of major importance,” [Edwin Frank] said. “It is regularly compared to some of the most famous German novels of the century: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. They would also compare them—as Uwe Johnson wanted to be compared, and consciously invited the comparison—to Proust and Joyce.”

That made the full translation of the book imperative in Frank’s eyes. “It’s a book that should exist in its entirety,” he said. “You don’t want to have just one volume of Proust. It seemed important to make it available that way. Not least because the bigness of it, and the range and scope of it, is what makes it such a pleasure.”

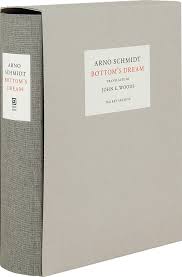

The only comparable publishing event of recent times that comes to mind is Dalkey Archive’s release of Bottom’s Dream by Arno Schmidt. This too was hailed as a masterpiece, praised by the literati (or Twitterati?) upon release, clocks in at over 1400 pages, and has been read in its entirety by not that many people. (And also appears to be out-of-print? That’s unfortunate. The book came out less than three years ago! Although it is impressive that it sold its entire—if press releases are to be believed—2,500 print run. That’s probably more copies than the German edition has ever sold.)

The only comparable publishing event of recent times that comes to mind is Dalkey Archive’s release of Bottom’s Dream by Arno Schmidt. This too was hailed as a masterpiece, praised by the literati (or Twitterati?) upon release, clocks in at over 1400 pages, and has been read in its entirety by not that many people. (And also appears to be out-of-print? That’s unfortunate. The book came out less than three years ago! Although it is impressive that it sold its entire—if press releases are to be believed—2,500 print run. That’s probably more copies than the German edition has ever sold.)

What makes these two publications events? Similar to last week’s post about an International Hall of Fame for Writers, there are no clear cut rules or criteria. But the fact that these two publications run so counter to contemporary trends (a penchant for novellas that are short, dark, and scary), yet are accompanied by a respectable amount of anticipation and excitement makes these projects fall into a slightly different category than your run-of-the-mill new-title-from-respected-international-author. (Not to throw shade, but this is the difference between NYRB/Dalkey Archive and HarperVia. That, and the fact that the quotes Edwin Frank gives to the press actually make sense.)

Which makes it really hard to figure out how to discuss these books. What does a valuable review of Anniversaries look like?

Thankfully—or thanks to Sara Kramer and Nick During?—there have been several. The New York Times (which, given the role it plays in the novel seems like a natural shoe-in for a solid assessment), The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Spectator, New Yorker, the Complete Review (where it received a grade of “A: Staggering”), etc.

All this is a long build-up to talking about “imposter syndrome,” something that quite a few of my friends have brought up lately. That feeling that their work—be it fiction, translations, blog posts, poems, scholarly articles—are lacking. That they’re a fraud on some basic level and are hustling and working some of that sleight-of-hand so that no one notices. Living in this age of anxiety and Twitter takedowns, it’s not terribly surprising; it is dispiriting to see so many talented people doubt themselves.

There’s a lot that could be unpacked about this—what success in 2019 looks like, where validation comes from in an age where everything is connected and instantaneous, how to trust your voice—but the reason it’s on my mind tonight is because of Christian Lorenzen’s article on book reviewing, “Like This or Die.”

I’m not going to rehash the whole article here (I really encourage you to read it in full to see the scope and construction of his ideas and arguments, and, if you’re curious, listen to the new Three Percent Podcast in which Tom and I share our opinions), but it has made me very aware of my own self-doubts, especially in terms of writing about books.

How should one review a literary event? Or should that be: How should one “review” a literary event? Or: literary “event”?

This reminds me of a Sam Miller comment on a recent Effectively Wild episode about what would make a scouting report of a superstar valuable? They were talking about a scout’s report on Peak Ken Griffey, Jr., who, for non-baseball readers, was a LEGEND. A true Hall of Famer, an unquestionably great player who the Reds eventually got from Seattle for players you definitely don’t care about. Anyway. Anyway! The point: A scout was assigned to write about “The Kid” and advise the front office of the Reds whether or not they should trade for him. Again, this is PEAK GRIFFEY. What could a scout possible say that the general manager doesn’t already know? “Saw Junior play. Really fucking good. Can hit and field. And throw. One of the best players in the game. Good at the baseball.” Is that valuable?

This reminds me of a Sam Miller comment on a recent Effectively Wild episode about what would make a scouting report of a superstar valuable? They were talking about a scout’s report on Peak Ken Griffey, Jr., who, for non-baseball readers, was a LEGEND. A true Hall of Famer, an unquestionably great player who the Reds eventually got from Seattle for players you definitely don’t care about. Anyway. Anyway! The point: A scout was assigned to write about “The Kid” and advise the front office of the Reds whether or not they should trade for him. Again, this is PEAK GRIFFEY. What could a scout possible say that the general manager doesn’t already know? “Saw Junior play. Really fucking good. Can hit and field. And throw. One of the best players in the game. Good at the baseball.” Is that valuable?

So what are book reviews—or blog posts, or whatever—supposed to say about a book that history has more or less already weighed in on, that, even if it’s not personally to your taste, is admirable and good? “Read Anniversaries. It’s fucking long. Real interesting though. Kind of compares the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany with the Vietnam War. An epic, unique book that would be impossible to replicate. If we had 25 of these books on our list, we would be a singular press.”

Are reviews just blurbs with a lot of extra words?

Paraphrasing Lorentzen, are reviews supposed to shift copies (a.k.a., serve as a mouthpiece for the publisher’s marketing plans), or engage critically with the text in a way that might illustrate flaws but also tends to have a more ambivalent relationship with the text, or should we abandon this mode entirely in favor of “coverage” that’s more easily digestible and much easier to heart and/or share? Or something else?

I try not to reflect on what this website has become all that often. Clearly, times have changed since we started this in 2007 with the intent of “covering international literature.” We’ve tried to be journalistic (I know! sounds insane now), we’ve been very opinionated, we’ve tried to focus on books on hype on publishers on the shareholders in the translation community . . . and maybe the site has always suffered from imposter syndrome?

So how can I possibly write about Anniversaries over the course of four posts? In a way that’s not stupid, not boring, and doesn’t repeat the same old clichéd observations? What value can this sort of readerly meditation have in book culture circa 2019? (I’m 160% going against the BuzzFeed belief that you should never put time into things that won’t get a lot of “shares.” But whatever. It’s my time. And if I wasn’t wrestling with existential ideas about what matters and what doesn’t and why are book reviews anyway then I’d be watching Temple play Belmont. Literally. Given that, I don’t think this is a waste of my time?)

So how can I possibly write about Anniversaries over the course of four posts? In a way that’s not stupid, not boring, and doesn’t repeat the same old clichéd observations? What value can this sort of readerly meditation have in book culture circa 2019? (I’m 160% going against the BuzzFeed belief that you should never put time into things that won’t get a lot of “shares.” But whatever. It’s my time. And if I wasn’t wrestling with existential ideas about what matters and what doesn’t and why are book reviews anyway then I’d be watching Temple play Belmont. Literally. Given that, I don’t think this is a waste of my time?)

All of that was supposed to be a one-paragraph introduction to my core idea: Pros vs. Cons.

Anniversaries isn’t for everyone. No book is for everyone. If you think a book is for everyone, I guarantee you that book is bad and isn’t for me. But given that I’m not about to spit out some kind of crazy contrarian take about how this book sucks, let’s at least have a little fun setting up some sort of dialectic so that people who were already going to give it a chance know what they’re getting into, and those who aren’t ever going to embark on an 1800-page journey through 1967-68 get a taste of what they’re missing. Maybe that’s what a book review can do. Not in the traditional format—smart contextualizing intro that proves the reviewer’s literary chops, synopsis of the book itself followed by quick analysis of major themes, bit of hand-wringing over potential pitfalls in the narrative or style or structure, followed by a gentile conclusion making sure we all remain literary buddies (again, paraphrasing Lorentzen, although I also feel like I’m paraphrasing myself with this)—but in a way that reflects the game Gesine plays with her daughter, Marie, when they’re recounting their earliest years.

The Novel Is Extraordinarily Long

Undeniable! Most books are like 70,000 words long. This thing has to be like 600,000. Or more. That’s a lot of words! If you’re the sort of person who is into logging your completed books on Goodreads and fulfilling your annual “challenge” of reading XX titles, this might jack your metrics.

If you’re someone more interested in living within a given world for a very long time (people who love the GoT? who must have some sort of self-identifying nickname, like “The GOTs” or “The Throners”? The Winter Elves?) and checking in with your favorite characters day after day, well then, this book is for you.

PUSH. Zero points awarded.

The Book Is Historical in Two Ways

As mentioned above, the book is set in America in 1967, during the Vietnam War, as the “flower power” is transforming, in the midst of great social unrest (race riots throughout the “Long Hot Summer of 1967”), at a point when America (and/or The World) could become very free and progressive or very capitalist in ways tinged with fascism.

As mentioned above, the book is set in America in 1967, during the Vietnam War, as the “flower power” is transforming, in the midst of great social unrest (race riots throughout the “Long Hot Summer of 1967”), at a point when America (and/or The World) could become very free and progressive or very capitalist in ways tinged with fascism.

That is the “now” of Gesine Cresspahl’s daily diary, which is Anniversaries.

As mentioned above, the book is set in mid-1930s Germany, when Gesine’s father moves back to Jerichow to live with her and her mother and her mother’s relatives (one of whom is a straight-up Nazi) during Hitler’s rise to power.

This is the story that Gesine is telling to her ten-year-old daughter. And recounting in her daily diary. (Is “daily diary” redundant?)

One point awarded FOR the book. A historical novel working in two timeframes, while clocking itself as a sort of proto-blog is definitely an appealing aspect of the novel.

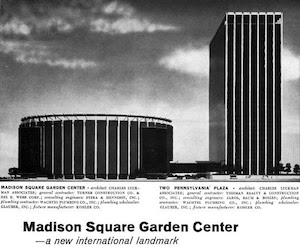

The New York Times Stuff Is Fascinating

Also mentioned this on the podcast, but most of the daily entries in the novel open with what was reported in the New York Times on that particular day. These usually take the form of: information about the Vietnam War, including the number of deaths; an account of civil unrest and/or a violent crime; some other random bit of information, such as a typo (Günther Glass instead of Günter Grass), or a general reflection of Gesine’s on the New York Times as if it were a stately old lady expressing her take on the world as a whole.

This is fun! I wasn’t alive in 1967, and it’s interesting to read about the coverage of Madison Square Garden being built. I wasn’t born too many years after 1967 (uuuugggghhhh) and this helps me feel more connected to the flow of history. (I remember having a similar experience while reading them by Joyce Carol Oates.)

This is fun! I wasn’t alive in 1967, and it’s interesting to read about the coverage of Madison Square Garden being built. I wasn’t born too many years after 1967 (uuuugggghhhh) and this helps me feel more connected to the flow of history. (I remember having a similar experience while reading them by Joyce Carol Oates.)

The most surprising moments in volume 1? That the NY Times ran a series of articles from Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana Stalina, in which she more or less defended her dad, while living in America. I had no idea this had been a thing, and the reactions to her being given this platform—with pretty minor rebukes—sound rather contemporary.

I wonder how some of the tragedies of 1967 strike other readers of the book. Personally, I’ve been of two opinions: 1) violence has always been a core part of this country, and b) why are things so much worse now.

POINT FOR. I can’t see how these bits don’t appeal to readers. 2-0.

There Is a Mafia Section That’s Out of This World

I think I might have fallen asleep, or read some pages after that second whiskey, when it came to the part about Karsch. Specifically, I can’t remember how this journalist/academic (or public intellectual? those existed in the 60s, right?) got hooked up with Gesine. But the two-three sections in which ten-year-old Marie answers a call from some mafia dudes who have kidnapped Karsch and want $2,000 (1967 dollars) to release him are WILD. They get the money. They drive from one shady location to another, following clues, eventually finding him tied up in the back of an abandoned shop . . . this is like an episode of The Sopranos in the middle of a Henry James novel. It’s insane, and kind of not believable? Unless 1967 academic (again, “academic?”) writers were like intrepid 2019 podcasters, willing to put themselves in crazy danger for a juicy story. (See: To Live and Die in LA, which I have very mixed feelings about, having loved the last episode but then finding out that the host is the same Neil Strauss who wrote The Game, which GROSS.)

I think I might have fallen asleep, or read some pages after that second whiskey, when it came to the part about Karsch. Specifically, I can’t remember how this journalist/academic (or public intellectual? those existed in the 60s, right?) got hooked up with Gesine. But the two-three sections in which ten-year-old Marie answers a call from some mafia dudes who have kidnapped Karsch and want $2,000 (1967 dollars) to release him are WILD. They get the money. They drive from one shady location to another, following clues, eventually finding him tied up in the back of an abandoned shop . . . this is like an episode of The Sopranos in the middle of a Henry James novel. It’s insane, and kind of not believable? Unless 1967 academic (again, “academic?”) writers were like intrepid 2019 podcasters, willing to put themselves in crazy danger for a juicy story. (See: To Live and Die in LA, which I have very mixed feelings about, having loved the last episode but then finding out that the host is the same Neil Strauss who wrote The Game, which GROSS.)

NEGATIVE ONE TO THE FOR. These sections are entertaining and wild and strange and cool, but I don’t necessarily get them? And they feel out of place. 1-0.

How Old Is Marie, Again?

Marie is 10. Ten years old. Do you know a ten-year-old? I do! I have a fifteen-year-old daughter (kill me) and an eleven-year-old son. How smart were kids in 1967? How independent? Pretty fucking? OK. Sure.

Marie rides the subway by herself all day when the three subway lines are integrated. She goes and gets groceries on a regular basis. She openly protests the Vietnam War in her private religious school. (More believable to me than anything else about her character, but then again, I’m raising non-binary anarchists.) Everyone in the neighborhood knows her and interacts with her like she’s an adult . . .

Marie rides the subway by herself all day when the three subway lines are integrated. She goes and gets groceries on a regular basis. She openly protests the Vietnam War in her private religious school. (More believable to me than anything else about her character, but then again, I’m raising non-binary anarchists.) Everyone in the neighborhood knows her and interacts with her like she’s an adult . . .

And yet, NYC is dangerous in 1967. Including the Upper West Side (they live on 96th).

Did Uwe Johnson have kids? Are NYC kids super advanced? Are my kids dummies? No ten-year-old I know acts/talks like this. None of them are this responsible and independent and untended. Maybe that’s a sign of the times? Maybe it’s just weird and hard to process.

ONE POINT AGAINST. 1-1.

A Sense of Place Is Worth a Thousand Paintings

The best aspect of this book is its atmosphere.

And again the machines contentedly gulping subway token after subway token on behalf of the Transit Authority, down throats grinding with pleasure that the riders set chewing inside the three-armed turnstiles up to five times per minute, maybe six times a minute, that would be some sixteen hundred an hour in the four lanes, that’s too many, and yet there are more than that. And again the heavy rumbling noise, audible through all the sways and jolts and braking processes, which betrays the excessive weight of the payload and reflects it in the base of the skull as a feeling of almost dangerous pleasure.

POINT FOR. 2-1

Uwe Johnson Is a Character

It’s always fun when the author shows up in his/her own work, right? Mostly? Sometimes?

It’s always fun when the author shows up in his/her own work, right? Mostly? Sometimes?

In Anniversaries, Uwe Johnson—who did live in NYC for a while—is giving a presentation about Germany to a Jewish organization, and doesn’t come off particularly well. He’s sympathetic, while acknowledging the recent election of a Nazi to West Germany’s government. It’s a humbling moment in the book (Johnson did grow up in East Germany, escaped when his writing career took off, lived in NYC, died in England), and a meta one.

The German who actually was there acted as if he understood not only English but the mood that had been prepared for him in the audience. He looked up at the cheerful, carefree speaker introducing him to the Jews. He was curious. From the room, the expression on his upturned face looked humorless and severe. Yet the jokes had been meant to be laughed at. Invited to the podium, the writer Uwe Johnson did not, say, leave the event at once (with thanks for the introduction) but instead began his talk in all seriousness, admittedly not with the late Middle Ages but still with the year 1945 and the subsequent development of two German states. He failed, however, to pull off the New England cadences he seemed to be trying to adopt for the occasion, and lapsed back into the wrong vowels, the wrong stresses, the not even British accent his school had let him get away with.

PUSH. Some people like that, others don’t. 2-1.

What Is the Novel’s Engine?

I can’t entirely put my finger on what makes this a page-turner (of sorts), but here are my best ideas:

- We have no idea how Gesine’s husband died or why she emigrated to America;

- We want to see how Gesine’s family—especially her father—pushed back against the rise of the Nazis. And how did that history all play out?

Speaking in the theoretical and general, I’m usually bored by family sagas. But something about this is compelling . . . I want to know what happens, and I want to sort through the various forms Johnson employs—first-person diaries, three-person recountings between Gesine and Marie, transcriptions of records, detailed accounts of things Gesine couldn’t possibly have been privy to, interior conversations with the dead, newspaper stories—to see how this all fits together. Is it a three-act play, or a four-season performance? What is the point of it all? Why exactly do I look forward to reading this book that I can’t get any of my friends to read?

This is where I am at the end of volume one. I’ll be back next month with some more thoughts. Imposter thoughts, most likely, but thoughts nonetheless.

Leave a Reply