Four Attempts at Approaches [Drawn & Quarterly]

This post comes to you thanks to a few different starting points: a box of translated graphic novels that Drawn & Quarterly sent me a couple of weeks ago, the fact that Janet Hong translated one of them (see last week’s interview), the fact that I don’t have time this month to read a ton of novels for these weekly posts, but can totally handle some graphic novels, and because part of my mid-life crisis is a desire to challenge myself and try new things. Like extreme amounts of exercise (at 43 I can still at least be in shape by book-people standards, right?) and trying to write about things I don’t already know how to write about. Like graphic novels.

That said, I am extremely familiar with comic books and graphic novels (total nerd! and yes, of course I saw Avengers: Endgame and Captain Marvel on opening night), but I’ve never tried to write about them in the ways in which I’ve written about translated fiction. Or even poetry. Although I feel like this post is pretty much in parallel with any of my posts on poetry in the sense that I know from the start that I don’t have the proper set of terms and concepts to clearly elucidate what makes a poetry collection “good” or “great” or “fine” or “garbage,” but I have some undefined, general understanding of what I like.

Since I haven’t even had time this week to steal a fun framework from Sam Miller, I think I’m going to simply write something about each of the four books I read, namely one aspect of what makes reading graphic novels interesting.

First though, a couple digressions. (Would this even be a Three Percent post if I went straight at that topic?)

Over the years, a number of people have asked me why we don’t track graphic novels in the Translation Database. The answer is so much more mundane and dumb than hoped for, but also has some odd corollaries. Basically, I can’t figure out how to get accurate, reliable numbers on manga published here in the U.S.

When booksellers or translators ask about graphic novels in translation, they usually are thinking of books from Drawn & Quarterly or Fantagraphics or First Second or NYRB Comics. They’re not necessarily thinking about Dragon Ball or Naruto or Fruits Basket or Death Note. All of which have tons of volumes available in English, mostly from presses I don’t regularly come in contact with.

This is unfortunate, especially since it results in Japanese works in translation being grossly under represented in the Translation Database. I have done a lot of research lately to try and capture all the Japanese “light novels” that have come out (again, thank you Rachel Cordasco), but manga is something I don’t currently have a hold on.

And so we end up with a weird situation in which, if I were to add the translated graphic novels that I do know about, it’ll ignore far too many Japanese works. OR, I could figure out all the manga, and all the D&Q/Fantagraphics/NYRB Comics books would be a pretty tiny percentage of all the graphic novels in translation that are available. Which actually makes me wonder what the language distribution really would be. Like 90% Japanese, 10% French, 10% everything else? I feel like Spanish graphic novels are a bit of a rarity, much less a book from the Balkans or Baltics.

Someday. Someday . . .

Shit Is Real by Aisha Franz, translated from the German by Nicholas Houde (Germany)

After an unexpected breakup, a young woman named Selma experiences a series of reveries and emotional setbacks. Struggling to relate to her friends and accomplish even the simplest tasks like using a modern laundromat, she sinks deeper into depression. After witnessing another couple break-up and chancing upon the jilted male of the couple, Anders, at his pet store job, Selma realizes that her mysterious neighbor is the woman of that same couple. Her growing despair distances her from from her eager and sympathetic friend. One day, as the mysterious glamorous neighbor is leaving for a business trip, Selma discovers the woman has dropped her key card to her apartment. Selma initially resists but eventually she presses the key to her neighbors lock and enters.

Aisha Franz is a master of portraying feminine loneliness and confusion while keeping her characters tough and real. Her artwork shifts from sparseness to detailed futurist with ease. Her characters fidget and twirl as they zip through a world both foreign and familiar. Base human desires and functions alternate with dreamlike symbolism to create a tension-filled tale of the nightmare that is modern life.

A book with a swear in the title—is this not the most “on brand” graphic novel for me to start with?

For this book, which I didn’t love as much as the others, but did totally enjoy, I want to highlight the idea that graphic novels are, for me, the Netflix of reading. Not just in terms of comic books as monthly “episodes” in a particular series, but in the way that you can generally finish a graphic novel in a few sittings, a few hours. In less time than it takes to watch Avengers: Endgame.

And as I’ve been reading these books, I’ve gotten so much gratification about being able to finish things. Contrast this with the—probably never–ending—projects of reading Anniversaries or Marie-Claire Blais. Not that one is “better” than the other, but the process of reading Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon over 55 audiobook hours and that of reading Shit Is Real over two beers on a Friday night is wildly different.

For me, personally, the main benefits are two-fold: 1) being able to actually finish something really triggers that lizard part of the brain that gives you an adrenaline boost for things like this, and 2) it’s much easier to think about a narrative’s “structure” if you can digest it in one or two sittings. Trying to keep the shape of Against the Day in my mind—over the FIVE months I’ve been reading it—is impossible. I have to keep rereading the synopses of each section, and reading other overviews. And will have to read a lot more after I’ve finished to try and hold all the pieces, all the storylines, all the ideas in mind at once to see how these things fit together.

A graphic novel can be like a good TV episode or miniseries in that you actually can hold the various parts in mind simultaneously and examine how things fit together or don’t. What the progression is, and how various scenes mirror or play off of one another. Narrative structures are fascinating, and it can be hard to pick them out when it takes a month/twenty hours to read a novel.

I don’t have a lot to say about Shit Is Real other than it was a bit heartbreaking and surreal and I liked that. And it had a lot of pages like these, which allowed me to be able to read it in one sitting:

And here’s a short review from Vulture that will give you a bit more context:

We take for granted that visions of tomorrow’s technology will be drawn with sleek lines and popping sheen, but Aisha Franz’s Shit Is Real tacks in the opposite direction, rendering a Black Mirror–esque world with chalky pencils and deliberately childish figure-work. The result is hypnotically surreal. It provides a backdrop for the achingly relatable tale of Selma, a woman who’s just been booted by her boyfriend and is trying to sort out her life while navigating a complicated friendship, recurring nightmares, and an awkward romance born in a pet shop. Sexual frustration and crippling loneliness abound, yet the book is curiously buoyant and consistently engaging

Red Winter by Anneli Frumark, translated from the Swedish by Hanna Strömberg (Sweden)

One thing that’s easy to dismiss—for non-comics readers—is the depth and weight of the stories told in graphic novels. Red Winter has all the makings of a novella, and was as much of a gut punch as anything else I’ve read this year.

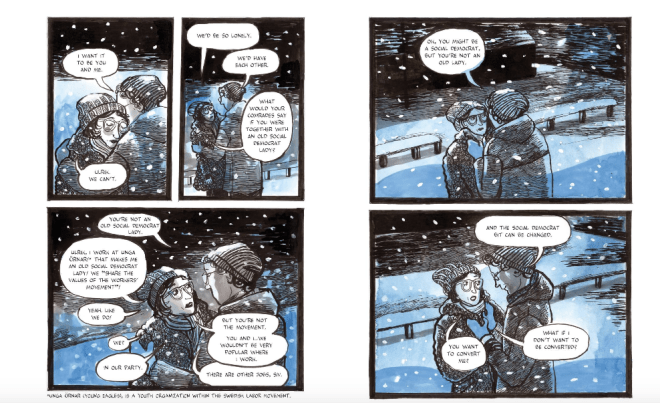

The story opens in media res and slowly unveils the situation of Siv (a married mother of three who lives a not-so-amazing home life with her labor-centric husband) and Ulrik (a young communist she’s having an affair with, who is trapped by his communist ideals and his age). It unfolds through a variety of perspectives, each section presenting the viewpoint of one of the characters impacted by this affair: Siv and Ulrik, obviously; but also Siv’s children, her husband, etc.

Granted, I’m a sucker for books in which various perspectives clash and bounce off one another, in which you can see the emotional motivations and rights and wrongs of each of the characters. But this affair, the doomed (1970s Sweden) aspect of it, the issues with the communist party at that time—they all hit home.

Although none of them are as impactful as when Siv’s daughter is left alone for the night. This section (54-?) is a testament to the sort of storytelling you can find in graphic novels that you can’t exactly replicate in a normal prose book. There’s a latent anxiety in the drawings, and in her actions exploring the house, answering the phone (and accidentally covering for her mom), her fears of waking up and finding that her mom still isn’t home . . .

Although none of them are as impactful as when Siv’s daughter is left alone for the night. This section (54-?) is a testament to the sort of storytelling you can find in graphic novels that you can’t exactly replicate in a normal prose book. There’s a latent anxiety in the drawings, and in her actions exploring the house, answering the phone (and accidentally covering for her mom), her fears of waking up and finding that her mom still isn’t home . . .

Again, I don’t have the right critical vocabulary at hand, but there’s something intriguing about how your mind fills in narratives in graphic novels based on existing tropes, subtle artistic elements, and unadorned dialogue. (By which, I mean, it’s perfect that graphic novels NEVER have “he yelled” or “he whimpered” or any other dialogue tag—the reader sees those tags and knows how the lines are being spoken.)

That same principle can be extended much more broadly though, to more complicated emotions and reactions.

And there is something compelling about allowing the reader to fill things in . . . I’ve always been a fan of the Cortazar/Calvino reader-interaction theories, but that’s a bit more limited with prose than it is in relation to graphic novels.

This was my favorite of the four books in this post. I’m not 100% sure I know why, but I really got into this. Read it in a sitting. Felt things. And enjoyed the cartooning and color palate:

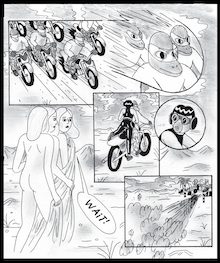

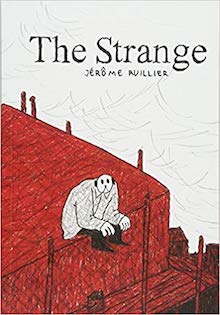

The Strange by Jérôme Ruillier, translated from the French by Helge Dascher (Madagascar)

Speaking of the art, let’s talk about The Strange, a graphic novel that’s likely going to get the majority of its attention because of its status as an allegory about immigration (and on that level, it is horrifying and unnerving), but for which the art does so much heavy lifting.

I hate talking animals in fiction. Drives me absolutely insane, since the rules about what the animal knows/doesn’t know (aka how much its simply a human in polar bear form), is usually inconsistent and logically troubling. Which then leads to a lot of questions about why you chose to use an animal to speak in the first place? And then shit goes sideways and I can’t focus on the narrative because I’m nitpicking over how a dog would or wouldn’t think and gah. Fuck books with animal narrators.

I hate talking animals in fiction. Drives me absolutely insane, since the rules about what the animal knows/doesn’t know (aka how much its simply a human in polar bear form), is usually inconsistent and logically troubling. Which then leads to a lot of questions about why you chose to use an animal to speak in the first place? And then shit goes sideways and I can’t focus on the narrative because I’m nitpicking over how a dog would or wouldn’t think and gah. Fuck books with animal narrators.

But then we have this.

All characters are “animals” in this book, emphasizing how “the stranges” stand out in this society. And for me, for that reason, it works. It’s not forcing some sort of bullshit logic, or over-explaining an animalistic perspective—it’s simply illustrating how society quickly identifies others as other. There’s a lot going on in presenting the protagonist of this graphic novel as a hulking dog, much larger than the duck/cat/mouse people who surround him. Is that realistic, or some sort of prejudice of the mind?

It’s also worth noting that this book (#19 on Paste Magazine’s “Best Comic Books of 2018“) is clearly French—and loaded with shitty quotes from Marine Le Pen—but could so easily apply to parts of 2019 America. Remember when the future was all flying cars and home robots, and not a burning trash fire, no water, and insane amounts of xenophobic hatred? Remember when “the future” meant something space age and glorious and not imminent doom? I know this is a digression, but things have gone off-the-rails, and I want to spend some time with some books/movies that present almost idealistic amounts of hope about the future, instead of seeing the next thirty years as the end of everything.

It’s also worth noting that this book (#19 on Paste Magazine’s “Best Comic Books of 2018“) is clearly French—and loaded with shitty quotes from Marine Le Pen—but could so easily apply to parts of 2019 America. Remember when the future was all flying cars and home robots, and not a burning trash fire, no water, and insane amounts of xenophobic hatred? Remember when “the future” meant something space age and glorious and not imminent doom? I know this is a digression, but things have gone off-the-rails, and I want to spend some time with some books/movies that present almost idealistic amounts of hope about the future, instead of seeing the next thirty years as the end of everything.

I mean, not to get too political—and this is a Chad W. Post statement, not anything from Open Letter or the University of Rochester—but it’s 2019 and we’re having states ban abortion. We are living in a backward world in which the wrong side is fucking up. Constantly.

Again: Not to get too political, but instead of wasting your time on this bullshit, why don’t you try and pass legislation so that my one-year-old son has even a 50% chance of living to the age of 80. Instead of being the worst combination of moralistic, misogynist, xenophobic, pro-Uber-capitalist, and just overall disconnected from people.

/end rant.

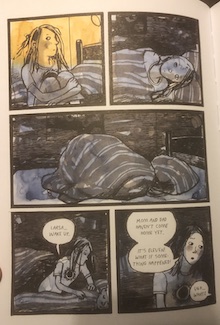

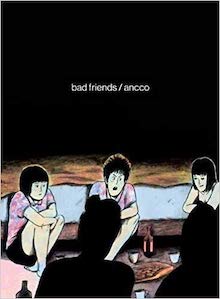

Bad Friends by Ancco, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (South Korea)

I have yet to talk about translation at all in this post. (Although, apologies again for a minor political interlude. @ me all you want. I kind of don’t care anymore.) But given that I talked to Janet already about this book—which is great! And violent! And quite complicated in its structure!—this seems like a good time to highlight a few issues in translating/publishing graphic novels versus doing the same for more conventional novels.

One of the big things—for both translators and publishers—is lettering. From a very pragmatic perspective, if you already have a book available in Korean, drawn with word bubbles of a particular size, you would prefer to change as little as possible and just replace the text in the original word bubble with words in a new language.

Obviously.

But if you’re going from Korean to English? How easy is that, really? There are a number of languages that require 20% fewer—or more—words when going into English, which is an insane percentage to think about when you’re talking about fitting these words into a specifically sized bubble.

That’s a logistical issue. One that translators don’t necessarily have to consider when they’re translating a novel.

Another thing: For the most part, graphic novels are told through dialogue. Which is one of the hardest things for translators to translate. Novels in translation that fail—or receive “toxic” reviews—are generally those in which the dialogue sounds flat or off or dumb or not native. Sure, every example cited here has some sort of first- or third-person narration, but dialogue still drives the majority of graphic novels. (I think.) And that makes it a trick thing! Get the tone right—in a predetermined amount of space/words . . .

Bad Friends is phenomenal, by the way. Maybe one day there will be a major U.S.-based graphic novel award in translation for this book to win. Because it deserves it.

Leave a Reply