Two Spanish Books for Women in Translation Month

Like usual, this post is a mishmash of all the thoughts I’ve had over the past week, mostly while out on a 30-mile bike ride. (I need to get in as many of these as possible before winter, which is likely to hit Rochester in about a month.) Rather than try and weave these into one single coherent post, I’m just going to throw it all at the wall and see what works . . . Here goes.

Twitter Hashtag Idea:

I’m still trying to stay off Twitter as much as possible, which is why I’m going to give you all this gift instead of trying to become cool by making something trend.

When I was at the Park Ave. Fest this weekend (Rochester’s annual beer pong tournament, er, crafts show, er, place for public drunkenness and violence, er, music-infused block party?) I saw someone with a shirt that said “Run Everything” in scratchy, unreadable font. I mistook it as “PUN Everything,” and assumed a ton of book people would love that.

A few minutes later I saw a guy wearing a shirt for the Syracuse Sriracha company that said “Syr-acha.” GROOOOAAAANNN. BUT! PUN EVERYTHING.

This would be a wonderful hashtag. Puns of book titles, products, movies, philosophical movements, whatever, all with #PunEverything. I suck at puns and will give lip service to how lame most of them are but . . . Well, I love G. Cabrera Infante and Pynchon, so . . . Give it to me. All you smart people out there—make #PunEverything happen.

Big Idea:

When I plotted out all of my posts for Women in Translation Month, one book I knew I was going to write about was The Promise by Silvina Ocampo, translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell and forthcoming in September from City Lights. Ocampo is a legend, and this, her longest work, has never before made it into English.

Add to that an intriguing premise—a woman falls overboard on a transatlantic voyage and, while she floats along for hour after hour, promises that if she survives, she’ll write her life story—and some really sharp prose (wonderfully rendered by two top notch translators) and you just know this book is going to be great.

Which is kind of the problem.

Given my respect of everyone involved in this project, along with the buzz the book’s been getting from people online who I trust . . . Well, what am I really going to say about this book? That it’s good? Should I try and analyze it completely? Put it in context of her other stories? Is that what the people want? A smart, well-constructed review of a book they should just go read because it’s written by a master who is often overshadowed by her male contemporaries? It might be! But not from one of my Three Percent posts . . . I don’t think that’s why any of you come here.

I already knew I would love and recommend this book, but that feels cheap. Where’s the fun in saying what you already assumed you would say?

But this gave me a grand idea: What if I could review twenty books from twenty publishers in as blind as a fashion as possible? I wouldn’t know the title, author, translator, or publisher for any of these. All the books would be so far out in the future that I wouldn’t have seen trade reviews or overheard anyone talking about these books at Winter Institute. I would have these all sent to my Kindle with titles like “Book 1,” “Book 2,” “Book 3,” and all put into the standardized Kindle font and layout so that my opinion couldn’t be impacted by the font choice or other design advantages.

Each week or so, I’ll review one of these books, writing about it in more detail than I usually do, since I’ll be trying to figure out what I like, if I think it works, etc., and assigning it a score between 5 and 20 in four categories: Style, Translation, Structure, Cultural Value. Adding those together, each book will receive a score between 20 and 80. (Which, coincidentally, is the same scale that scouts use when evaluating baseball prospects. Coincidentally.) And I’ll try and guess who the publisher is. And the language it’s translated from.

Anthony will serve as a point person for this, tracking all the titles that I’m going to review and making sure that the texts I receive are 100% stripped of telling details. At the end, I can rank all twenty books, and Anthony can unveil which titles were which. And we can see how my evaluations match up with BookMarks, Twitter buzz, all the various lists, etc.

I think this would be fascinating! Like reading a slush pile but without an eye toward rejecting everything, but instead trying to assess what made a publisher want to publish this book.

If you’re a publisher, expect an email laying this all out later this afternoon and asking you to participate in my crazy scheme.

And if you’re not a publisher? Prepare yourself for some wild posts. And go buy The Promise. It’s really good. I’ll leave you with a quote from early on:

Marina Dongui, the fruit vendor, was the first to appear involuntarily before me in my memory. Blonde, pale-skinned and jittery, she’d come to the door of the fruit shop whenever I’d pass by with my brother and wink at him. Her breasts were like certain fruits overflowing her neckline, and my brother would pause to look at her—but what am I saying?—not at her but rather at her breasts, and not at the navel oranges which were very expensive.

So good.

It’s Always the X of Y:

I see this ad on Instagram A LOT, and I usually just scroll on by. But today, for whatever reason, I stopped to actually read it and came away very confused.

What is going on here? What does the “Netflix of Coffee” even signify? Can you binge it? Is it coming out with 72 new coffees every week? Is it about to lose its more popular properties to some other sort of coffee startup? Who is Nick? Why does it matter that he’s from Savannah? Is Savannah known for having really knowledgeable wordsmiths who can make very apt comparisons? Like, “Trade Coffee is the Netflix of Coffee”?

The Controversial Part:

Another book I wanted to write about here was The Remainder by Alia Trabucco Zeran, translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes, available in the UK from And Other Stories and in the U.S. from Coffee House.

Almost a polar opposite to my reaction to The Promise, in this case, I didn’t know what to say about this book because I mostly ended up skimming it—and couldn’t figure out why. It’s not a bad book by any means. It’s on the Man Booker International longlist, so obviously it’s good and a lot of people will like it. It’s told through two narrators, Felipe, who wanders Santiago, Chile counting down all the dead bodies he finds/imagines, and Iquela, who is Felipe’s childhood friend, and a translator with a complicated relationship to her parents.

The main plot point is that Paloma—whose parents were friends with Iquela’s during the dictatorship, but escaped to Germany—has returned to Chile to bury her mom, who has recently died of cancer. Unfortunately, due to a volcanic eruption that left the city looking like this:

The plane with the coffin was diverted to Mendoza. So the three get a hearse and go on a road trip to retrieve it. And they drink Pisco along the way.

I’m not a huge fan of the invented dialect for Felipe’s sections, but I respect what Sophie Hughes is up to with those. But aside from that, there’s nothing concrete I can point to as to why I lost interest in this book, why I started thinking “this just isn’t for me.”

I was going to insert a poll in this post to see how all of you interpret the phrase “this just isn’t for me,” but I’m 99% sure I know the answer: It’s a nice way of saying, “I don’t think this is very good.” At least that’s how I feel if I see someone say that about one of our books. And then I block them. And vent in my office for five minutes. And then forget about all of it, given how crap my memory is becoming.

But that’s not what I mean! I really feel like in a different time and place, I would’ve enjoyed this book more. Which might be different from “not for me,” but only kinda sorta.

Are there other ways to interpret “not for me” that aren’t so immediately knee-jerk negative? Sure!

1.) A book’s genre/aesthetic isn’t something you understand.

I feel this way every time I try and write about crime novels. Not that they’re not for me, but they’re not for me because I don’t read them with enough regularity to know all the nuances of the genre and the little nods and diversions an author might be playing with. A really good mystery might not be for me, because it’s too well-constructed for me to really get it.

2.) A book’s joys don’t align with your personal joys.

This goes back to an idea I hammered to death a few years ago: Books provide various sorts of rewards to various sorts of readers. Immersive, descriptive prose is mirrored in your mind, triggering neurons that would fire if you were actually experience what you’re reading. People like that! Check that. Most. Most people like that. Others like puzzles and having to swim through a torrent of words to try and figure out what’s going on. People who are into immersion must hate these books. (Think: Finnegans Wake.)

And these desires aren’t fixed by any means. Sometimes you want one sort of book, sometimes another. And if you end up with the wrong one at the wrong time? All its most uninteresting aspects are the ones you focus on.

Although there is a distinctive style to The Remainder, I was having a hard time focusing on that instead of just flipping ahead for the next plot point to drop. This is on me, but I’ve been working on a couple titles that fall into that second category, and really am desperate for something complex and convoluted, a book that I have to think through, revisit, puzzle out.

3.) A book is explicitly meant to empower a particular subset of readers.

Everyone can get something out of a given book. And everyone can learn from a socially aware book. For sure. We should read books from perspectives not our own. But I can totally respect a book that’s going to be much more of rallying cry for women or POC than for middle-aged overweight white dudes. Even if I love a book like this, I might be tempted to say that it’s not really for me, because I know that I don’t get it the way that its target audience does. Terrible example, but I’m totally there for Captain Marvel, but I kind of feel like that movie is really for my daughter—not only to feel like a female superhero can be the most bad ass, but so that my daughter learns who Elastica was.

4.) A book for a different generation.

One of the last times I saw the Twitter involved some long thread about overrated books or whatever. And the thing that always jumps out at me about these sorts of conversations is how books that you read in high school—which are meaningful if you’re in high school—show up here as overrated. Which isn’t exactly right. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with the books, but you really should just move on from Catcher in the Rye. (And, sorry, Harry Potter.) Certain books are written to be read by people at a certain moment in life. On the Road. You can respect them later, I suppose, but they’re really only impactful if you’re at that exact right stage of life. Sophie’s World. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. There are so many YA titles that are probably just fine, but “not for me.”

One Chart:

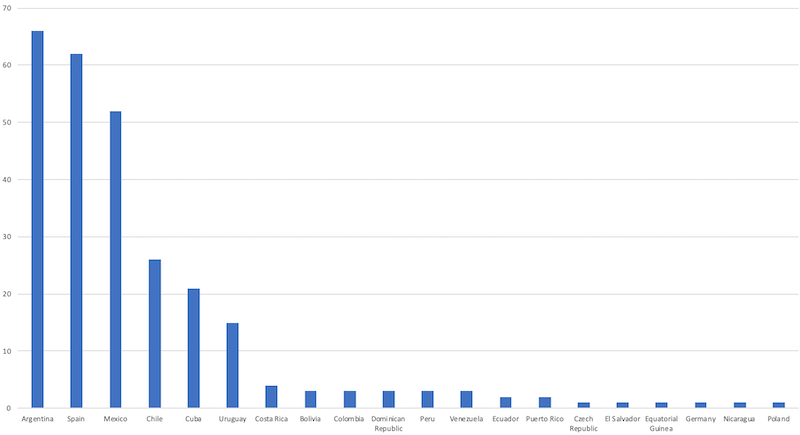

I’m going to post a new #WITMonth chart every Wednesday, but since both of these are translated from Spanish, I want to put up a graph of where all the books by women writing in Spanish have come from since 2008.

Not terribly surprising, and I suspect this would look rather similar for male authors, with Argentina, Spain, and Mexico leading the way, and most Central American countries being very underrepresented. Still, it’s interesting to see it laid out like this.

Leave a Reply