Perversity’s Politics [BTBA 2020]

Today’s Best Translated Book Award post is from Hal Hlavinka, a writer and critic living in Denver. His work has appeared in BOMB Magazine, Music & Literature, Tin House, and others.

Some books are made of fucking—of cum and cumming, cocks, twats, and tongues, desires of all kinds. A la Gass, literature may arrive in different shades of blue: some the color of morning, an erection at sunrise, a shadow sexual tension undispersed by the night; others darkened to purple in their perversions, heavy, overwrought, fit to burst. For the prude, such books might be vulgar; the aesthete: garish; the reactionary: obscene; the fanatic: forbidden.

The state versus Molly Bloom deemed her language “unparlorlike.” In the UK, the Obscenity Act of 1959 sunk its teeth in Mr. Lawrence for a few “fucks” and “cunts.” Naturally, Nabokov, fine purveyor of pedophilia and incest, won his share of bans, for works that stand at the outer edge of linguistic profundity, and his public’s decency. Then, for a time, it seemed the dam had broken, as we moved into this century, unmoored by neo-liberalism, cavorting all we like between the pages, with naught but the odd local library acting the iron-clad censor.

So enter our fresh fallen world: in America, with 30% of our neighbors unmasked as bigots, white supremacists, and, for what seems like something of a first, self-styled vulgarians, untethered, finally, by a reality star’s innate vulgarities; and abroad, with all manner of buffoons, conmen, and plutocratic libertines taking the reins across every hemisphere, their pale faces framed, dead-eyed, on all of our screens, grinning through their malice. And, though the Left has historically held the mantle of obscenity in art and cultural life, that pride increasingly seems property of the Right, the alt-right, the fascists, who bear it happily against calls for decency, normality, and truth. Where once perversity was an aesthetic and political tool for critiquing power, for digging into its cracks to expose any rot, the obscene has now been subsumed by power itself. The emperor is naked, and his subjects adore it.

What’s to be done? Well, down with decency, I say, and bring back a version of truth-telling fiction that doubles down in its most vulgar strategies. And what better weapon to bring to this struggle against the arch xenophobes than books from outside our borders.

From The Shadows—a slim, strange 2016 novel by Spanish author Juan José Millás, and translated this year by Thomas Bunstead and Daniel Hahn for Bellevue Literary Press—traffics in a kind of perversity that flickers between comedy and domestic horror and, ultimately, economic alienation. The protagonist, Damián Lobo, recently fired from his job, spends all day imagining himself a celebrity on an extended TV interview. Early in the novel, the imaginary interviewer starts a line of questioning that brings Damián to the subject of his adopted Chinese step-sister, two years his senior. What starts as a sequence of questions lining up an adolescent crush in an unusual family arrangement, quickly drops into out-and-out incest. As the story progresses, Damián flees a petty theft by hiding in a wardrobe, which is in turn delivered to a family’s home. There, he becomes something like a phantom servant, cooking and cleaning and spying on the father’s hapless affair with a co-worker, until his phantomhood reaches a kind of violent apotheosis. It’s a novel where perversion leads to alienation in an absolute sense: from the bonds of a family via incest; from one’s own labor through capitalism’s rapacious march; and from personhood through a total disengagement with the world. In the end, all that’s left is a male gaze, obsessive, extreme, detached from life’s logic.

From The Shadows—a slim, strange 2016 novel by Spanish author Juan José Millás, and translated this year by Thomas Bunstead and Daniel Hahn for Bellevue Literary Press—traffics in a kind of perversity that flickers between comedy and domestic horror and, ultimately, economic alienation. The protagonist, Damián Lobo, recently fired from his job, spends all day imagining himself a celebrity on an extended TV interview. Early in the novel, the imaginary interviewer starts a line of questioning that brings Damián to the subject of his adopted Chinese step-sister, two years his senior. What starts as a sequence of questions lining up an adolescent crush in an unusual family arrangement, quickly drops into out-and-out incest. As the story progresses, Damián flees a petty theft by hiding in a wardrobe, which is in turn delivered to a family’s home. There, he becomes something like a phantom servant, cooking and cleaning and spying on the father’s hapless affair with a co-worker, until his phantomhood reaches a kind of violent apotheosis. It’s a novel where perversion leads to alienation in an absolute sense: from the bonds of a family via incest; from one’s own labor through capitalism’s rapacious march; and from personhood through a total disengagement with the world. In the end, all that’s left is a male gaze, obsessive, extreme, detached from life’s logic.

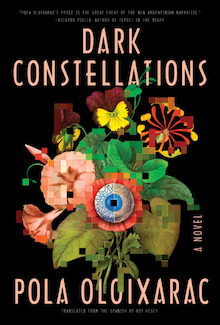

In Dark Constellations—a 2015 novel by Argentine writer Pola Oloixarac, newly translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey for Soho Press—sex underlies the techno-evolution of capitalism, as a form of exchange, currency, and domination. A few apt scenes: the story opens on the Canary Islands in 1882; the intrepid explorer, Niklas Bruun, arrives to the hidden village of Mahan, where a fertility rite begins that will forever connect the Europeans “into the genetic history of the island in a torrent of semen and blood.” The novels second storyline introduces Cassio, a young hacker in the 80s, by-way-of the fuck that founded him. His mother, Sonia Liberman, has an affair with a Brazilian man, for whom she is exclusively a sexual object, and, naturally, a lack of protection and care leads us right to young Cassio, who grows into his own passages as an incel, for a time. In the final section, set in Bariloche, the now-techno-futurist hub of South America in 2024, a young female professional wears VR glasses and watches two Komodo dragons ravage a blonde woman in explicit detail, and masturbates. Each of the novel’s narrative strands uses sex as its own distinct critique of our ideological past, present, and future—be it colonialist, chauvinist, or techno-utopic. The sexual is always political, and this wonderful, maximalist little novel wields ribaldry like a gun aimed at capitalism’s amoral heart.

In Dark Constellations—a 2015 novel by Argentine writer Pola Oloixarac, newly translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey for Soho Press—sex underlies the techno-evolution of capitalism, as a form of exchange, currency, and domination. A few apt scenes: the story opens on the Canary Islands in 1882; the intrepid explorer, Niklas Bruun, arrives to the hidden village of Mahan, where a fertility rite begins that will forever connect the Europeans “into the genetic history of the island in a torrent of semen and blood.” The novels second storyline introduces Cassio, a young hacker in the 80s, by-way-of the fuck that founded him. His mother, Sonia Liberman, has an affair with a Brazilian man, for whom she is exclusively a sexual object, and, naturally, a lack of protection and care leads us right to young Cassio, who grows into his own passages as an incel, for a time. In the final section, set in Bariloche, the now-techno-futurist hub of South America in 2024, a young female professional wears VR glasses and watches two Komodo dragons ravage a blonde woman in explicit detail, and masturbates. Each of the novel’s narrative strands uses sex as its own distinct critique of our ideological past, present, and future—be it colonialist, chauvinist, or techno-utopic. The sexual is always political, and this wonderful, maximalist little novel wields ribaldry like a gun aimed at capitalism’s amoral heart.

Leave a Reply