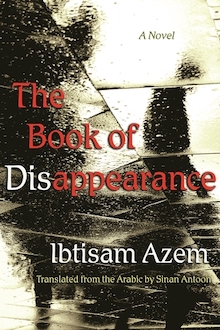

“The Book of Disappearance: A Novel” by Ibtisam Azem

The Book of Disappearance: A Novel by Ibtisam Azem

Translated from the Arabic by Sinan Antoon

256 pgs. | pb | 9780815611110 | $19.95

Syracuse University Press

Review by Grant Barber

This wonderful, important second novel by Ibtisam Azem in English translation came out just in time for the observance of Women in Translation month—a month in which publishers, translators, authors, booksellers highlight English translations of works by women who write in other languages. Azem is a journalist of Palestinian heritage living in NYC. A credit to her imagination and writing is that one of the main characters in her novel, The Book of Disappearance, flips her own biographical matters: Ariel is male and Jewish, also a journalist filing reports in the opposite direction, to his editor in NYC from Jaffa, the town immediately south of Tel Aviv.

Although other characters appear written from a third person perspective—the chapter headings tell the reader whose perspective we are receiving—the other major voice is Alaa’s. He is a second-generation, internally displaced Palestinian who, along with the rest of the Palestinians living within their ancestral borders, vanishes one night. He was born into a family headed by a matriarch, his grandmother, who remained in Palestine after the creation of Israel in 1948—called by Palestinians the Naqba, the disaster, when 700,000 people left or were expelled from their homes.

The novel starts with the frantic search for Alaa’s grandmother, whom he finds upright, seemingly at peace, and dead. She is seated on a bench overlooking the sea in her beloved hometown of Jaffa. The city and the heritage it contains are strong forces of meaning, nostalgia, and character.

This report of the search turns out to be the start of a diary that Alaa kept, a running commentary addressed to his grandmother about memories, family members and events, his grief at her death as well as the losses she endured, reflections on place, history, and what it means to be a people. This diary has been left behind, discovered by Ariel after the vanishing of Palestinians living in the loosely defined (for the world of the novel) area of Palestine overlapping with Israel. Ariel, a liberal, more secular Jew, lives in the same building as Alaa. They were friends of a complicated sort, with keys to each other’s apartments.

Much of these basics are discursively laid out on the back of the book. What I’d claim is that the bare bones description—the characters, the disappearance without explanation or evidence of mass actions—does not capture the seeming light touch of storytelling by effective authorial voice and prose. Even when the thoughts of the characters turn toward some of the most horrific events of the region, the prose does not confront as much as describe and account. One of Azem’s strengths is that essential skill of showing, not telling. More than once after finishing the novel I would open it up to hunt down a character’s name or a sequence of events and be drawn right back into the story, well beyond finding the answer I sought.

An example of showing: after Alaa’s disappearance, Ariel focuses on his journalist duties, and is not getting much sleep. He climbs the stairs down to Alaa’s apartment; he lets himself in, which leads to him nosing around a bit—like checking out what there is to eat—and then falls asleep, exhausted, on Alaa’s bed for the night. He returns to sleep there again for the next several nights. The literary trope one might be looking for is the realization of “we’re all the same in the end,” or the mourning of the absence of a friend with new insight into unappreciated qualities. But, nope, not even a hint of any change in Ariel indicating empathy. The difference of just a flight or two of stairs is not sufficient a reason. Nothing about the apartment is touted as better—size of rooms, morning light, nothing.

In the Middle East Monitor, reviewer Romana Wadi points out the simplest, most logical explanation for Ariel’s behavior: the reflexive impulse to take over Palestinian dwellings and property. Ariel might represent a progressive viewpoint of Jewish Israelis, but he also seems comfortable repeating some of the rationalizations that try to cover the discomfort of knowing that hundreds of thousands of people had been displaced, sometimes with great violence, from homes in which they and generations before them had grown up. Alaa’s diary recounts a few conversations he had with Ariel when the topics turned toward those tensions, the anger just below the surface that can’t be willed away. By the end of the novel Jewish residents nearby have started casing the empty houses left behind, some with a view of the sea…wondering how and when they might lay claim. The Israeli government passes a law naming an arbitrary day and time by when the Palestinians must show up in person to reclaim their property, or it will be forfeit. The country as a whole seems to stay awake until that 3 a.m. deadline, waiting to see if this law was enough to bring the Palestinians back. It doesn’t, and the initial right of return that was established early in Israel’s modern existence but since blocked—echoes again.

For all the inescapable politics inherent here, Azem portrays people with complicated relationships—Alaa’s mother to his grandmother, fathers of both Alaa and Ariel, a former wife and present lovers of the men. The flow of the novel is smooth, an effective, almost-placid surface under which are deep waters, faster currents, dark places. This novel would make an excellent one for a book club interested in fiction as a door into current challenges.

Once again, a side-matter is that of genre. The besetting event seems like science fiction, a fairy tale or a one-trick magical realism move. The rest of the novel has a realist bent. Perhaps this novel is one more artistic work that makes the need for pigeon-holing novels into genres increasingly irrelevant. From Sterne to Stein to Calvino, and the translator’s own fiction—Antoon in his most recent novel veers outside the constraints of genre—the inclusion of the unexplainable seems actually truer to real life than a Sinclair Lewis or Stendhal novel.

Syracuse University Press merits mention and thanks for its dedication to literary works from the Middle East. It is in company with the U of Texas Press and its Latinx fiction series; the University of Nebraska’s series of fiction in translation; Wake Forest and Irish poetry; Yale Margellos; and University of Rochester’s Open Letter Books. Inherent though is the lower commercial profile all of these great sources of literature in translation into English. One can hope that novels and novelists such as Azem will continue to be supported and promoted on a wider English stage. Some really great work is out there every publishing season.

Leave a Reply