We’re Still Here . . .

“We live in a world of randomness.”

—William Poundstone, The Doomsday Calculation

It probably goes without saying, but publishing international literature is a precarious business in the best of times. On average, sales for translated works of fiction tend to be about one-third of the average sales for a mid-list author writing in English. There are additional costs—not just in terms of paying the translator, which is baked into the idea of publishing books from around the world and shouldn’t be something publishers complain about—such as increased expenses to tour an author, the mental stress of having to work approximately ten times as hard to get the same level of attention given to books written by Americans, the fact that most translation-centric presses are non-profits, which means that in addition to all the normal publishing tasks, you also have to spend a significant amount of time filling out grant applications and final reports, running fundraising campaigns, cultivating major donors, and working with a board of directors.

Richard Nash used to say that all indie press publishing is two fuck-ups away from collapse. Presses specializing in international lit? We might only be one fuck-up away. Or one COVID-19.

Just because I have the tendency to ramble, I’m going to drop the lede right here, then circle back: Open Letter needs your support more than ever before. Everyone’s struggling, there are hundreds of worthy causes and orgs to donate to, but if you like our books, our free content, our role in the translation-ecosystem, please consider donating to us. I don’t want to sound alarmist—or at least not more than is warranted—but we need a lot of things to break our way to continue operating like we have for the past thirteen years.

Last post, I shared a graph of how our sales fell off the ledge in April, seriously jeopardizing our chances of having our best year ever. (Which we were on pace for through March!) But, in a way, that chart is misleading. The numbers are all accurate, it’s just that this chart is basically everyone’s chart. (Unless you work in the booze industry! According to an ad on Instagram, liquor sales go up 243% during quarantine. Which, well, um, that data has to be a sample size of one, so . . .)

The long-term consequences of lockdown, of having 20% unemployment, of dealing with uncertainty and fear of a future outbreak will be screwing things up for the foreseeable future, no matter how much Trump and protestors want to wish that away.

Which brings me to my actual point: Open Letter isn’t just suffering because it’s hard to sell a lot of books right now, but because more than a third of our revenue comes from the University of Rochester. The education crisis is so pervasive and terrifying—and impossible to address as a whole—but thanks to sending students home, refunding room & board fees, having worries about fall enrollment, and employing large numbers of people whose jobs don’t directly generate revenue, higher ed is in some massive trouble.

I don’t have/won’t share the specifics about the University of Rochester, but I was forced to furlough Kaija for two months and Anthony for three weeks, and every division on campus is taking a hit to their budget. It doesn’t help that the UR Medical Center is losing $130 million/month and is furloughing 20% of its staff.

All of this is to say that things might be evolving at Open Letter over the next months and years. In the current environment, the model we’ve been operating under doesn’t seem sustainable. What will this mean? Nothing drastic right now, but we’re going to have to reassess how we allocate our resources. Which may include having to cut back on the altruistic things we do for the larger community (from posts about other press’s books, to podcasts, to running weekly translation workshops, to speaking with whomever asks for advice), since these are all unfunded.

Again, if Open Letter is at all a meaningful part of your literary life, I hope you’ll consider donating to us. The U of R’s donation site is a bit clunky, since you have to “select a designation” choose “other-write in” and then write in “Open Letter,” but it can be done. Or you could mail us a check directly if that’s easier. For worse, these appeals from us are going to become much more commonplace—even after “all this.”

*

OK, now that that’s out of the way—sorry, but if you knew the level of anxiety and uncertainty I’m dealing with in regard to the press you would know just how restrained those above paragraphs really are—let’s get to the fun stuff!

So, this week’s post is actually three posts, a triptych of posts. (If you’ll forgive a bit of pretentiousness.) There are linkages between the three, and I’m actually experimenting with writing all three simultaneously, but, to be honest, they’re each pretty separate from one another.

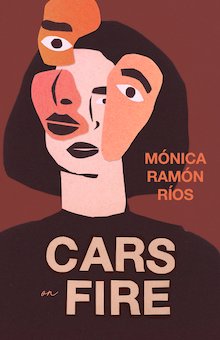

I want to start this one by recommending Cars on Fire by Mónica Ramón Ríos, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers. This was our April publication, officially releasing on April 14th, which isn’t great for a book that was positioned to take off thanks to bookseller love and recommendations . . . Just check out this quote from a *starred review* in Publishers Weekly: “Ríos’s themes are unwaveringly contemporary—LGBTQ and feminist issues; immigrant life; politics—but it is artistry, not dogma, that guides her prose. This is art house literature at its best: provocative, alluring, and uncompromising.”

I want to start this one by recommending Cars on Fire by Mónica Ramón Ríos, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers. This was our April publication, officially releasing on April 14th, which isn’t great for a book that was positioned to take off thanks to bookseller love and recommendations . . . Just check out this quote from a *starred review* in Publishers Weekly: “Ríos’s themes are unwaveringly contemporary—LGBTQ and feminist issues; immigrant life; politics—but it is artistry, not dogma, that guides her prose. This is art house literature at its best: provocative, alluring, and uncompromising.”

These stories are fierce. As mentioned above, they’re uncompromising in both their stylistic approach and political aims. They’re fun, yet unnerving. They’re playful in form, without fear of experimenting. (“Invocation” is told in two voices running in parallel down the pages.) They are, in short, fire.

This is going to be the next Two Month Review book (official schedule to come, but we’ll be talking about it live on June 3, 10, and 17, and both Mónica and Robin will be honored guests), so I’d highly recommend ordering it now so that you’ll have it in time.

To celebrate the release of COF, the Southwest Review ran this incredible conversation between Ríos and Myers, which I wholeheartedly recommend reading in full. But here are a few fantastic bits:

Robin Myers: I’d like to ask you instead: how did the collection come to be structured for you? And in what ways did you feel, as you wrote the stories, that they were speaking to each other? As I translated, I sometimes imagined them as a kind of song series: one completely different musical experience after another, jarring and thrilling in their contrasts, their color-scapes. But sometimes I thought of them more as a chorus: all speaking up at the same time, all claiming their place in a kind of riotous multiplicity. I’d love to have you discuss the relationships among the stories as they revealed themselves to you.

Mónica Ramón Ríos: The urge to write these stories emerged, among other things, from a localized, experiential, desire-based knowledge/belief that the self is a perilous fiction that has been imposed on us both by very good literature and by very poor books. And I say this not because I read all the poststructuralists (which I did) or the postmodernists (which I ditched), but because I rebel against the idea of fixity, of borders, walls, names, or any supplementary tools to define being, voice, or even our work as anything more than fiction. I learned to write at a time when Chile was plagued by very bad neoliberal realism, which coincided with the most treacherous moments of Chilean politics: when the left sold the country and settled with the dictatorial right to create a new transactional structure of power—this is the order we are trying so hard to remove right now in Chile. In terms of literature, the transparency and immediacy of neoliberal realism was not only trying to oppose the literature of the ’80s (a dense oppositional, feminist, queering, literature of protest against univocal dictatorial violence, but also of military stupidity, embodied by the Ministry of Censorship). At the same time, in fact, neoliberal realism was trying to hide those power transactions. And it meant wanting to write like the gringo literature exported to Chile because the whole country wanted to enjoy their fucking McDonald’s. What came out of that was not literature, but a new writer who was a vendor, a new literature that was a product. It wasn’t even entertaining, because it made you lethargic, like the joints mixed with glue we’d buy on the cheap as teenagers to pass days that felt eternal and useless. This was a literature without consequences. But even back then, we still craved those moments of intense understanding that made us become trabajadores de la letra, writer-workers.

So, yes, the voice of Cars on Fire is a riot. I wrote all of the short stories, except one, after moving to the United States. And in many ways their voice also riots against the inherent racism in this country, especially the one concealed behind niceness. I aim my pen at those people who abuse us saying they are helping us, saying they are our friends.

RM: It seems to me that two of the central forces at work in the book are, on the one hand, the human thirst for revenge (explored especially in part one, “Obituary”), and, on the other, the exhilarating multiplicity of love and desire (which particularly characterizes part two, “Invocation”). Part of what fascinates me about the book is how your ventures into the intentionally exaggerated or even the fantastical—I’m thinking of the comical distortedness of the academic administrator in “The Head,” the amorphous creature in “Extermination,” or the sinuous human-animal metamorphoses in “Invocation”—affects the dynamic between your characters and their environments, or with each other. Or would you object to my use of the word “fantastical” here? Maybe what I’m really asking is how you see, and like to channel, the slipperiness of place, time, and form in your work.

MRR: I would rephrase it as Mónica Ramón’s thirst for revenge and their desire for the exhilarating multiplicity of love. I see the stories you’ve mentioned as pure realism. I say this with a mischievous intent to contend the possibilities of the real and to subvert the straitjacket that has constricted our experiences.

Again, read the whole thing here.

Also, check out this interview with Robin Myers that’s part of Caroline Alberoni’s “Greatest Women in Translation” series;

CA: Besides being a translator you are also a poet. Does being a poet help as translator and vice-versa? If so, how?

RM: It absolutely helps. Both poetry and translation (and by this I mean the translation of anything, not just poetry) are practices rooted in the materiality of language. If you write poetry or translate anything, you are in the business of dealing with words as stuff, as resources, as concrete elements you shape and combine to form certain structures and spark particular effects in the reader. Of course, in translation, you’re using language in response to—in relation to—language that already exists in the world. You’re writing (because translating is also writing) in the service of and in complicity with that language. In this sense, too, translation demands both that you saturate yourself with the original text and that you distance yourself from it. That doubleness has helped me write my own poetry, I think, at least in the sense that it’s made the experience of writing poetry much more interesting. For one thing, it’s made me more conscious of the artifice of whatever I’m doing (and I mean “artifice” not as an insult but as a fact). For the same reason, it’s also made me feel freer to experiment: to think with more curiosity and more gratitude about language as “tools” and how I might try them out. I do feel that writing poetry affects my translations as well, or my approach to translating. For example, I care a great deal about sound when I write poetry, about what happens to words when we string them together and speak them aloud, and I feel a similar need to “hear” what language does in translating both poetry and prose. That said, I don’t mean to talk about this obsession with sound as if it were strictly the domain of poetry, much less of poets, because that’s not the case at all! I’m just musing about what it feels like for me in going about things as I go about them.

Also, you can purchase Robin’s most recent poetry collection, Tener/Having, in a beautiful bilingual edition from Antílope Press in Mexico.

Final thing! On Wednesday, May 13th at 7pm eastern, you can see Mónica Ramón Ríos in conversation with Carmen Boullosa via Books Are Magic.

*

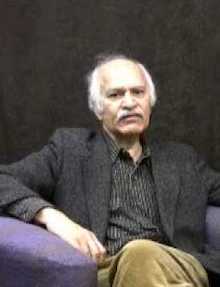

Sticking with the idea of these biweekly posts being some sort of quarantine reading diary, I have to take a paragraph to praise Zulfikar Ghose’s Kensington Quartet. This isn’t coming out until September, but it’s a truly beautiful book. I mostly know of Ghose from the issue of the Review of Contemporary Fiction that featured him (together with Milan Kundera), but his life and career are fascinating.

Born in Pakistan, he lived in London in the 1950s and 60s, then moved to Texas in 1969. He’s written a dozen novels, and an equal number of poetry collections and works on nonfiction. He even co-authored a book of short stories with personal favorite B. S. Johnson. (Hulme’s Investigations into the Bogart Script sounds particularly interesting to me. Especially in combination with Patrik Ouředník’s Case Closed (trans. Alex Zucker), which is near the top of my to-read pile.) He’s been praised by T. S. Eliot!

For whatever reason, the books that have worked best for me in quarantine have been British. Or at least set in London. Escapism + mid-50s British charm works for me. Which is why I plowed through Kensington Quartet in just a couple days.

It’s a tricky book, a book of memories and nostalgia in which the narrator is wandering around London, remembering earlier versions of himself as if they still physically exist. It’s a short novel of memory and landscape, an ode to London that will appeal to lovers of Esther Kinsky or other meditative, geography of memory type, flaneur writers.

It also opens in Kensington Gardens following almost the exact same path I walked when I was there on March 10th, before the world completely fell apart.

I am here now, just inside Kensington Gardens.

To the north the pebbled concrete expanse of the Broad Walk slopes up towards a pale blue sky above Bayswater. Two women with bundled-up toddlers and another pushing a pram, and farther up shadowy figures of three men in charcoal-grey coats, there is a scattering of ghostly bodies on the Broad Walk, the light so unusual, almost too bright, aglow in my mind, a surprisingly illuminated London. Glancing back in the direction of Palace Gate, I observe that you are striding up in that jaunty walk of yours, always so enthusiastically eager for the grass under the elms and a view of the Long Water. There are no shops to distract you, only consulates of foreign lands across the road you have no interest in, one displaying a flag, green and white, of indistinguishable nationality, hanging too limply. Your step always quickens in Palace Gate when the distant green blur of Kensington Gardens first catches your eye and even when the day is overcast and grey you see a sudden green shiver in the sky, for you it’s the pulse of London, throbbing, as if it were your blood that surged with a sudden passion and made your breath come hard and loud—as that first time, that April, which then became the loveliest of months, when the first of English green you saw was here—all those prints of Constable’s landscapes in the Blackie readers coming alive in the grass at your feet—and your blood bounded in amazement. Another three minutes and you will be coming into the Gardens, inflating your chest when you enter, as is your habit, taking a deep breath and holding it a long moment as when the doctor, his stethoscope’s cold disc on your chest, says, Breathe in and hold, listening to your heart.

Ghose’s writing is simply delicious. The more grounded moments—of the narrator’s first experiences in school, when he nearly has a fling with a gay friend of his teacher’s, when things don’t work out with his various girlfriends—are conventionally compelling and well-crafted, but it’s in the long descriptions, the meanderings, the way that he constructs a palpable sense of London that the prose excels. In a way, this book is a throwback. The narrator’s life resembles Ghose’s in some superficial ways, but it doesn’t feel like the “I” fiction so predominant these days. It’s an attempt to create something beautiful and heartfelt, an archeology of emotional memories tied to a very specific place.

*

Last bit of self-promotional stuff . . .

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve participated in two virtual events to support Four by Four by Sara Mesa, translated from the Spanish by Katie Whittemore. Since neither space nor time really make sense anymore, I thought I’d share both of them here.

First up was the Wordplay event with both Sara and Katie. This one is bilingual in a fun way, mostly about the book and Sara, and features one of the funniest event moments I’ve seen, when Katie flees her daughter and her daughter’s “Let it Go”-playing birthday card.

Designed to be a complement to that event, the one Katie and I did for the Transnational Series at Brookline Booksmith is all about translation, crafting voice, interesting challenges Katie had to deal with, and a fun “mercenaries vs. soldiers” bit.

I hope you enjoy both, and please buy a copy of the book from one of the two organizations that hosted us!

please add me to your list for translation information articles