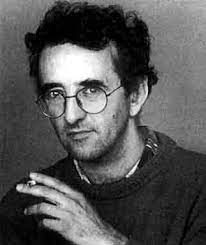

Season 16 of the Two Month Review: “2666” by Roberto Bolaño

2666 has been a potential TMR title right from the jump and now, years after launching this podcast, we’re finally going to tackle one of the most discussed and admired works of Latin American literature of the past century, translated by Natasha Wimmer:

“Composed in the last years of Roberto Bolaño’s life, 2666 was greeted across Europe and Latin America as his highest achievement, surpassing even his previous work in its strangeness, beauty, and scope. Its throng of unforgettable characters includes academics and convicts, an American sportswriter, an elusive German novelist, and a teenage student and her widowed, mentally unstable father. Their lives intersect in the urban sprawl of Santa Teresa—a fictional Juárez—on the U.S.-Mexico border, where hundreds of young factory workers, in the novel as in life, have disappeared.”

That’s . . . pretty succinct for an almost 900 page book. Jonathan Lethem’s review in the New York Timesadds a bit more detail for anyone on the fence about whether to read along with us this season or not:

“In the literary culture of the United States, Bolaño has become a talismanic figure seemingly overnight. The ‘overnight’ is the result of the compressed sequence of the translation and publication of his books in English, capped by the galvanic appearance, last year, of The Savage Detectives, an eccentrically encompassing novel, both typical of Bolaño’s work and explosively larger, which cast the short stories and novellas that had preceded it into English in a sensational new light. By bringing scents of a Latin American culture more fitful, pop-savvy and suspicious of earthy machismo than that which it succeeds, Bolaño has been taken as a kind of reset button on our deplorably sporadic appetite for international writing, standing in relation to the generation of García Márquez, Vargas Llosa and Fuentes as, say, David Foster Wallace does to Mailer, Updike and Roth. As with Wallace’s Infinite Jest, in The Savage Detectives Bolaño delivered a genuine epic inoculated against grandiosity by humane irony, vernacular wit and a hint of punk-rock self-effacement. Any suspicion that literary culture had rushed to sentimentalize an exotic figure of quasi martyrdom was overwhelmed by the intimacy and humor of a voice that earned its breadth line by line, defying traditional fictional form with a torrential insouciance.

Well, hold on to your hats. [. . .]

2666 consists of five sections, each with autonomous life and form; in fact, Bolaño evidently flirted with the notion of separate publication for the five parts. Indeed, two or three of these might be the equal of his masterpieces at novella length, By Night in Chile and Distant Star. In a comparison Bolaño openly solicits (the novel contains a series of unnecessary but totally charming defenses of its own formal strategies and magnitude) these five long sequences interlock to form an astonishing whole, in the same manner that fruits, vegetables, meats, flowers or books interlock in the unforgettable paintings of Giuseppe Arcimboldo to form a human face.

Lethem does go on to describe each of the five sections in detail (again, you can read it all here if you’re interested), but I think that’s enough for now. I mean, it’s kind of weird trying to “sell” 2666. This book won the National Book Critics Circle Award (but not the Best Translated Book Award!), and has more or less been canonized as a classic. It’s a book that people tend to revere, and, like Lethem mentions, it ushered in a new Golden Era for Spanish-language literature. Bolaño was that rare figure who broke through the stereotypes about international literature in translation, to become, at least among the literati, a household name.

If you haven’t read 2666 before, buckle up. It’s wild, it’s fun, it’s disturbing. And yes, it’s long. But this really is a book that reads fast, thanks in large part to Bolaño & Wimmer’s style.

Given the popularity of—and amount of criticism written about—Bolaño, we’re sure to have a great lineup of guests this season. Additionally, we’re bringing on a semi-regular third co-host this time around: translator and

Given the popularity of—and amount of criticism written about—Bolaño, we’re sure to have a great lineup of guests this season. Additionally, we’re bringing on a semi-regular third co-host this time around: translator and Bolaño expert Katie Whittemore. She wrote her thesis at Cambridge on 2666, reading the book almost upon publication, before the true explosion of interest had gripped the world. Additionally, Katie recently translated Last Words on Earth by Javier Serena, a book that uses aspects of Bolaño’s biography to explore ideas of the artist’s life, myth-making, fame, and more. In the words of Tobias Carroll:

It’s hard to read Last Words on Earth without thinking of the late Roberto Bolaño, but this novel pulls off the feat of evoking his life without feeling like a thinly disguised biography. Serena’s prose also abounds with minute details told in sprawling sentences, as when we learn that the writer at the heart of the novel “offered technical commentary akin to that of an opera lover” when watching pornography. Concise, bold, and moving.

So there will be lots to talk about. And as you can see below, this season will take us through the end of the year, which even though 2021 was no 2020, it still feels like an accomplishment to make it through another year of weird. And what better way to wrap it up than with a truly classic book.

Since Katie lives in Spain, this season’s live recordings will take place on Tuesdays at 9am on our YouTube channel, with the audio-only podcast coming out every Thursday morning. The dates below correspond to the live recording dates, but obviously, take this at your own pace. If you do watch us live, you will have the chance to comment, ask specific questions, etc.

10/5: Introduction to Bolano10/12: pgs 1-7510/19: 75-159 (End of Part 1)10/26: 160-228 (End of Part 2)11/2: 229-30011/9: 300-349 (End of Part 3)11/16: 350-43711/23; 437-51511/30: 516-57512/7: 576-633 (End of Part 4)12/14: 634-72112/21: 721-80612/28: 806-end (End of Part 5)

Finally!

Thanks guys – despite your 15 previous seasons, I have not listened before. Very much looking forward to following along with this 2666 read through.