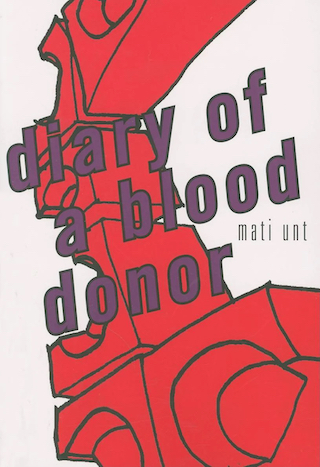

“Diary of a Blood Donor” by Mati Unt [Excerpt]

Diary of a Blood Donor by Mati Unt

translated from Estonian by Ants Eert (Dalkey Archive Press)

AN UNEXPECTED INVITATION

A crow was riding the wind that came in low over the beach. Sand blew through the window, landed on my papers, entered my mouth. A yellowish light tainted the room, even my fingers. I carefully reread the letter from this morning’s mail, but it remained impenetrable. A complete stranger, writing in Russian, wanted me to meet him next Sunday in Leningrad where the cruiser Aurora was docked.

Next Sunday, Leningrad, Aurora?

A week from no, hundreds of kilometers from Tallinn?

What’s going on?

Having explained nothing, the letter’s last line threatened: This meeting in vital.

It was unsigned.

The kind of letter that should go right into the garbage. Except . . .

Except:

Vital for whom? For me? Him?

Is it an emergency?

Have I inherited a fortune?

Am I dealing with a spy?

A seductive woman?

A wealthy foreign publisher?

What have I overlooked?

Are they luring me away to be murdered?

Is it an admirer of my novels?

Or some poor bastard about to die?

Army counterespionage?

I put the letter away again, and for the third time decided not ot go anywhere. Am I a marionette to be yanked around on a string? An anonymous letter arrives and immediately I get ready to run off on a fool’s errand.

Who’s the fool?

Apparently it’s me.

As an obscure writer, freedom fighters and spies tend to ignore me. It’s true that once in a while letters come to enlighten me on some brand-new world order or synergy, with copious details appended. But the cruiser Aurora, the cradle of revolution, the ship that fired the shot on October 25, 1917, signaling the beginning of the assault on the Winter Palace—what’s it got to do with me? Sure, my life has been affected by that infamous shot, but so have the lives of the thousands of people around me. Will all of us now be called to the Aurora? Perhaps it’s only those who approve of the revolution? Or only those who disapprove? If I alone was invited, how was I selected?

As an obscure writer, freedom fighters and spies tend to ignore me. It’s true that once in a while letters come to enlighten me on some brand-new world order or synergy, with copious details appended. But the cruiser Aurora, the cradle of revolution, the ship that fired the shot on October 25, 1917, signaling the beginning of the assault on the Winter Palace—what’s it got to do with me? Sure, my life has been affected by that infamous shot, but so have the lives of the thousands of people around me. Will all of us now be called to the Aurora? Perhaps it’s only those who approve of the revolution? Or only those who disapprove? If I alone was invited, how was I selected?

No, this is just a silly joke. Or maybe revenge? But for what?

What have I done?

Everyone’s guilty of something—am I any guiltier than anyone else?

That’s it: I’m going to ignore the letter.

Using the last packet my Finnish publisher had sent me, I brewed some coffee, added sugar I had obtained with my ration card, and to steady my shaky nerves, invented all sorts of excuses for doing nothing: gas stations are out of gas, trains are overbooked, buses are overcrowded—I can’t travel at all, our Great State is in a lot of trouble. Gas has all but disappeared because the rail services that bring it in have been almost completely shut down. Public transportation is bone dry too. Am I supposed to walk to Leningrad? I do have some bread left; no point in going to the grocery, since there’s also a sausage shortage on. Shortages promote self-reliance. At least something good has come out of this mess, thank God: There’s nothing to be gained by going out. Let them write and invite. I’ll withdraw, learn to know myself, tell the world to go to hell; I can’t be bothered watching the end of the world, won’t cry at its grave. Far better to stay on the sofa with its springs poling me in the ass—there are no upholsterers available, and anyway no sofa covers. I do have some soap saved up, a whole cake; I’ve even hoarded a tube of toothpaste. There’s no way I’m going down to the cruiser Aurora. I’ll ignore everyone and everything. Of course, poverty and lack of means shouldn’t really be an excuse for turning one’s back on adventure. A colleague of mine recently visited North Korea, and another one went to Mongolia. Far away corners of the world, where the sun is hot and the people and their habits are inscrutable. Going to the cruiser would be a new experience, no? I might get a short story out of it, or the beginning of a novel? The last living member the Czar’s family wants to reveal everything to me, yet here I sit, stretched out on a shabby sofa, protecting my ivory tower.

What if terrorists are planning to blow up the cruiser, and I’d have a front-row seat for the event? Front-row seat? Or maybe I’d be blown up with the ship?

I’m not sticking my neck out.

Still, I guess the ship could sail and take me along. I’ve written about the ships and the sea. I did write a commemorative article on Lennart Meri, but that hardly qualifies me as a naval historian.

Am I being accosted by a radical organization getting ready to set off another revolution and planning to blow up the Aurora in order to publicize their cause? And afterwards they’ll supervise a ceremonial casting of flowers onto the waves? And make endless, boring speeches? But in that case the letter would have had a declaration in it, a slogan or two. If I was being courted by revolutionaries, I would’ve been invited to a bar in some dank cellar, not a pier. So, could it be a woman who adores me? But in that case the letter would have had at least a few loving words in it—especially since I’m known to be such a sucker for sentimentality. A homosexual, perhaps? I’ve never been mistaken for one, and in any case, the symbolism here—a long ship with big guns and a proud prow splitting the waves—is just too obvious.

Could it be something to do with the subconscious? The Flying Dutchman? Long John Silver? Moby Dick? The ship of transcendence, its mast pointing up at the North star, following the axis of the Earth? Could it be I’ve been invited to the White Ship that everyone is waiting for, the ship that never comes to our shores except to bring us across the Styx?

But the letter is matter of fact. Fine sand settles on my papers. I stand by the window.

A PICTURE FROM MY YOUTH

The cruiser Aurora fired her gun on the night of October 25, 1917, and after that she toured Helsinki and Kronstadt. In 1946 she became an icon on the Neva River.

Many old ships have earned their retirements.

The “Oseberg” Viking ship near Oslo.

Fitzcarraldo’s ship in the rain forest.

The following happened in a youth camp at Värska in 1964.

I’ve forgotten the names of the camp commandant and his staff, but I do remember that the project was progressive. None of us were there looking for glory or an easy way up the bureaucratic ladder by supporting the prevailing ideology. A few of us were in our twenties, but most were still in middle school, barely fifteen years old. I do remember Mark Soosaar—now a film director—who at that time was a MC on the radio. I remember Mati Polder and Aare Tüsvälja too—they were television personalities. But things were different in those days. At night we caught crawdads, which may or may not have been a prohibited activity. We had lively discussions by the campfire, but the gist of our arguments, unfortunately, has escaped me. But I repeat: we were certainly progressive.

Värska, in the extreme Southeast of Estonia, is in a province of Setumaa. No wonder then that the wasteland there, where practically nothing grows, is called the Setumaa Sahara.

One day we took a walk in that desert. To avoid the heat we set out at dawn, but when the sun came up, the cooling wind disappeared. Scraggy bushes offered no shade. We walked for a long time. Sweat poured off us, and the water cans were empty. Exactly where we went I have no idea. No one wanted to be the first one to quit. On the contrary, the stronger people in the group seemed to be enjoying the misery of the weaker. We did pass a couple of farmsteads, where no one was to be seen. Duke Ellington’s “Caravan” sounded from one of their windows. It suited th occasion. We kept on going through the parched vegetation. Far away we heard some explosions—probably the Russian Air Force conducting exercises on the lake. Why a lake? Explosions over water sound different. Then, the figure of a fleshy, sun-baked, half-naked man appeared out of nowhere. He spoke gibberish, vaguely like our own language, but we didn’t understand a single word. Had his tongue been cut out? Lonely places guard many secrets, and witnessing something illegal can be dangerous. Perhaps his attacker was humane. Instead of killing him, he just made sure the witness couldn’t tell tales. How much can one reveal by waving one’s arm? Had we accidentally stumbled on some high political conspiracy? Or perhaps the man was drunk? Was there another possibility? The bravest among us indicated that we were thirsty. The man made agreeable noises, beckoned. After some hesitation we followed him. Surprise! Behind a bush was a boat half buried in sand. Two of the side planks were broken, and on the board where the rower would normally sit, a lizard lazed in the sun—it quickly escaped. Our guide sat in the boat and took to rowing with imaginary oars. Was he acting out how he, in some gray time, arrived here, or would in some golden time depart? The man muttered something, as if inviting us to board the boat. We raised a cloud of dust getting away from him. Soon we were on our own again. It was possible that a long time ago this had been the shore of the lake. Maybe the boat had belonged to the grandfather of the tongueless man, a guerrilla in the last war, who had needed to hide his boat from the enemy?

One day we took a walk in that desert. To avoid the heat we set out at dawn, but when the sun came up, the cooling wind disappeared. Scraggy bushes offered no shade. We walked for a long time. Sweat poured off us, and the water cans were empty. Exactly where we went I have no idea. No one wanted to be the first one to quit. On the contrary, the stronger people in the group seemed to be enjoying the misery of the weaker. We did pass a couple of farmsteads, where no one was to be seen. Duke Ellington’s “Caravan” sounded from one of their windows. It suited th occasion. We kept on going through the parched vegetation. Far away we heard some explosions—probably the Russian Air Force conducting exercises on the lake. Why a lake? Explosions over water sound different. Then, the figure of a fleshy, sun-baked, half-naked man appeared out of nowhere. He spoke gibberish, vaguely like our own language, but we didn’t understand a single word. Had his tongue been cut out? Lonely places guard many secrets, and witnessing something illegal can be dangerous. Perhaps his attacker was humane. Instead of killing him, he just made sure the witness couldn’t tell tales. How much can one reveal by waving one’s arm? Had we accidentally stumbled on some high political conspiracy? Or perhaps the man was drunk? Was there another possibility? The bravest among us indicated that we were thirsty. The man made agreeable noises, beckoned. After some hesitation we followed him. Surprise! Behind a bush was a boat half buried in sand. Two of the side planks were broken, and on the board where the rower would normally sit, a lizard lazed in the sun—it quickly escaped. Our guide sat in the boat and took to rowing with imaginary oars. Was he acting out how he, in some gray time, arrived here, or would in some golden time depart? The man muttered something, as if inviting us to board the boat. We raised a cloud of dust getting away from him. Soon we were on our own again. It was possible that a long time ago this had been the shore of the lake. Maybe the boat had belonged to the grandfather of the tongueless man, a guerrilla in the last war, who had needed to hide his boat from the enemy?

Somehow we made it back to the camp. In the cool of the evening, we rowed across the river to a nearby camp of university students. We lit a fire on the bank of the river with two friendly young women and tried to get kissed—but nothing; I think they were each keeping an eye on the other. When it began to rain, we rowed back to our won camp. By this time the eastern sky was blushing red. On the way I quoted Ristikivi: After you left, you became a dream, but in my bed, my suffering continued. The morning brought on more philosophical discussions; we all voted for increased middle-school and university-student autonomy. That day was just as hot.

Having fashioned a grave

From the sea, darkness exudes

Terror where a whale-like

Aurora haunts the night

—Vladimir Mayakovsky

Leave a Reply