93. What does sleep do besides just give us rest?

93. What does sleep do besides just give us rest?

It allows our brain to clear toxic waste that left alone could lead to neurological disorders.

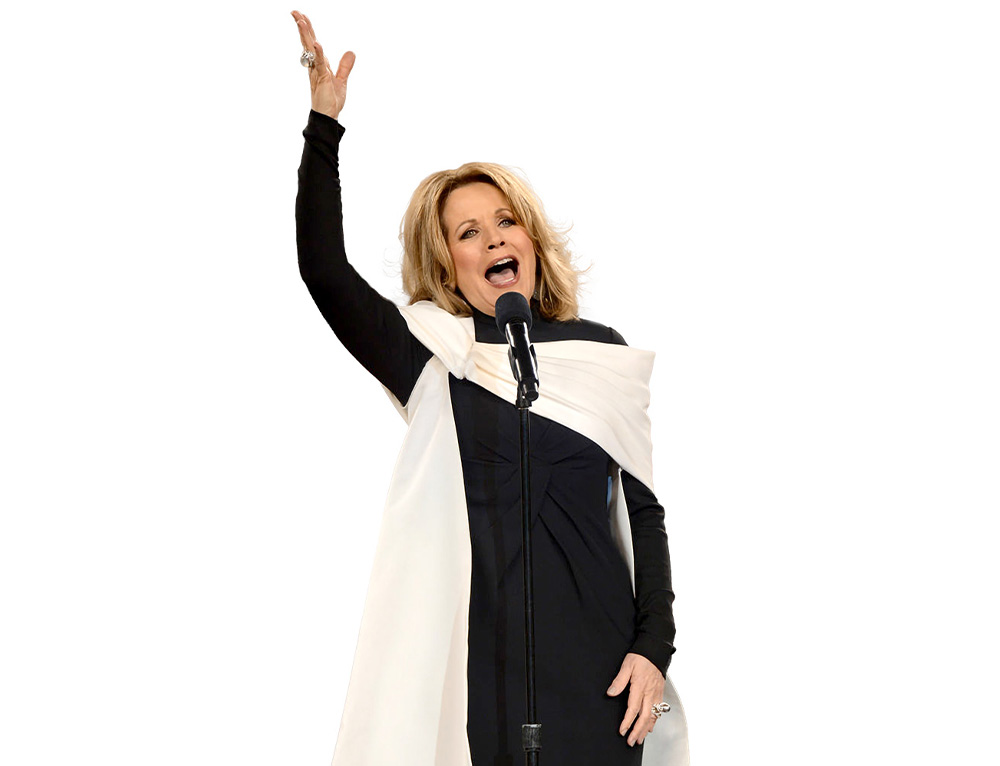

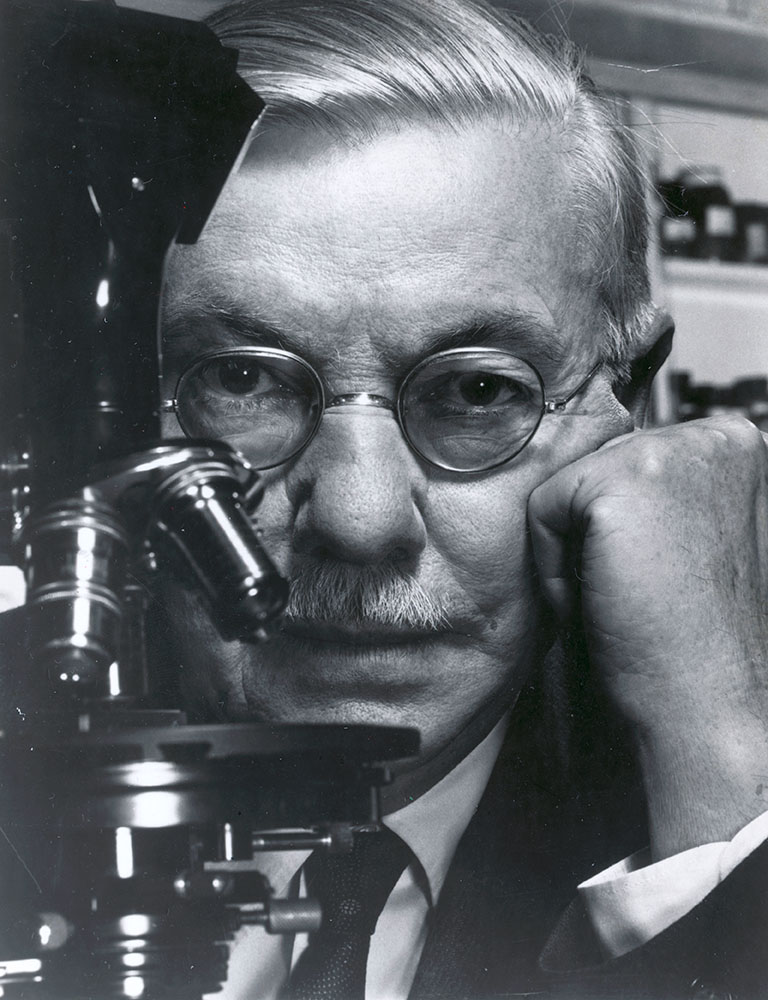

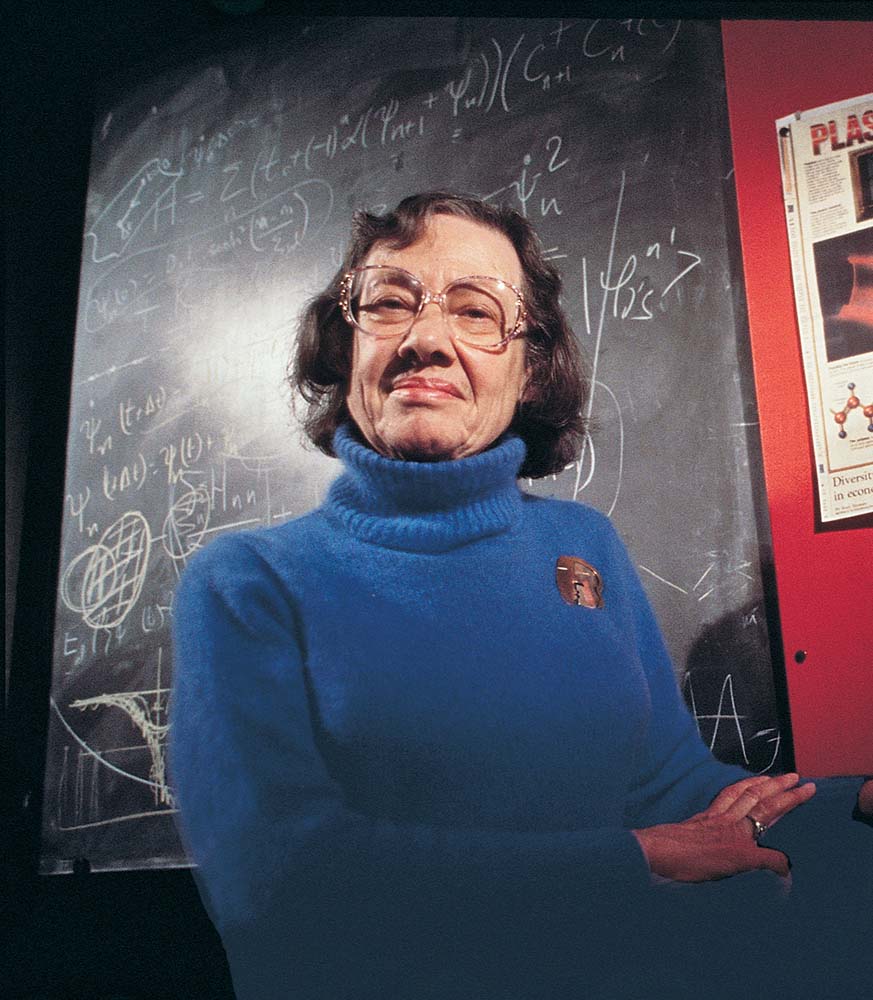

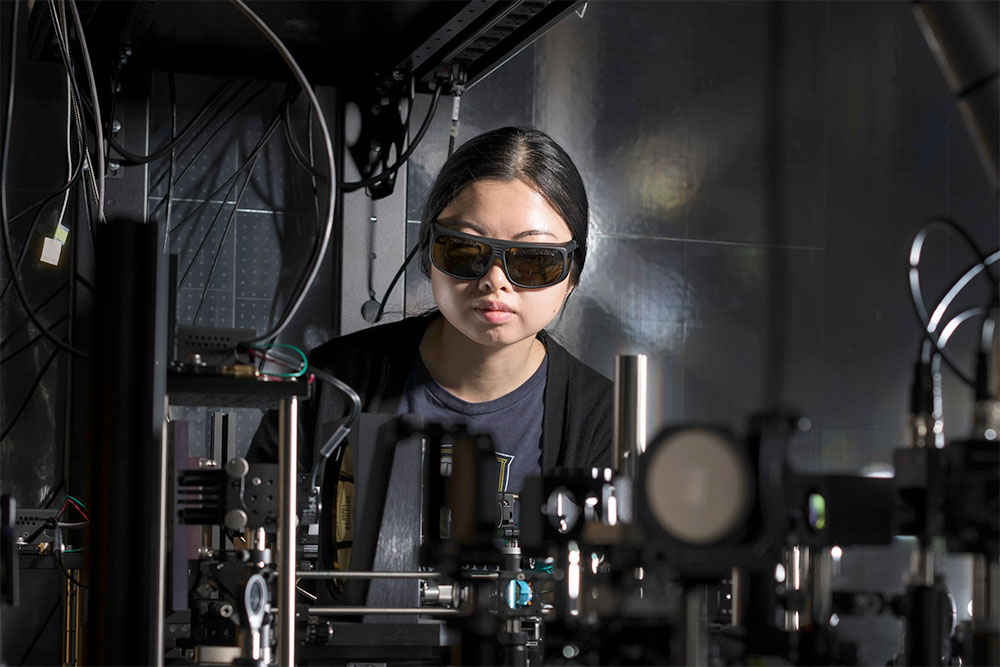

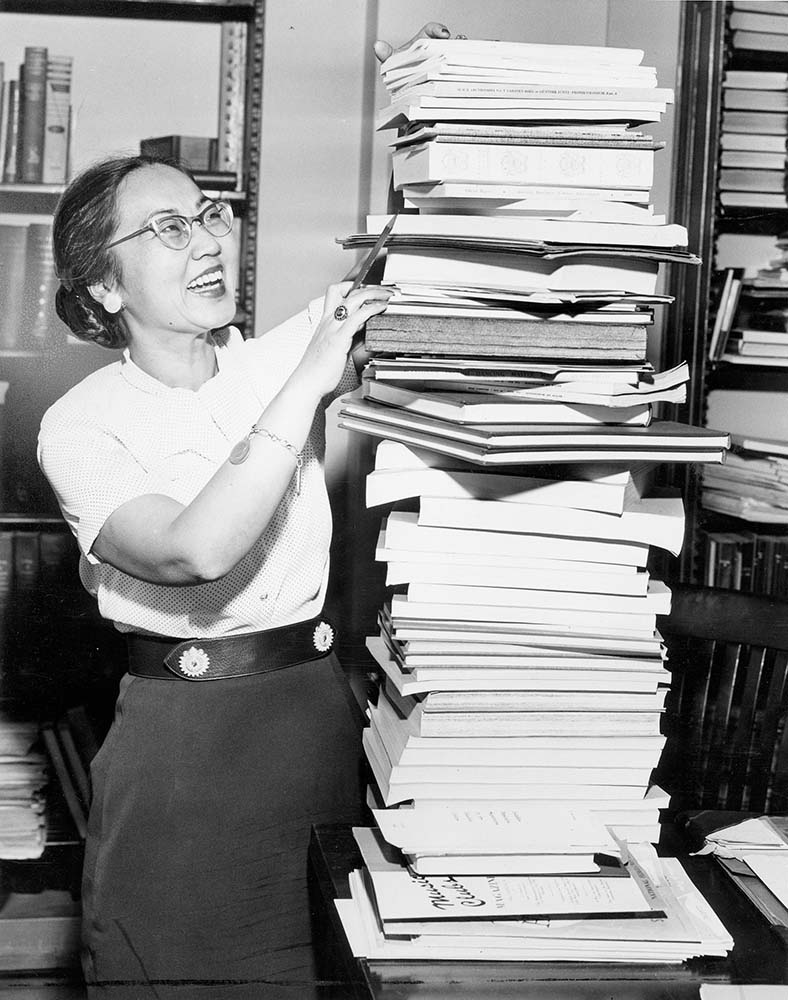

With her discovery of the glymphatic system, URochester neuroscientist Maiken Nedergaard fundamentally reshaped our understanding of brain physiology and the biological purpose of sleep.

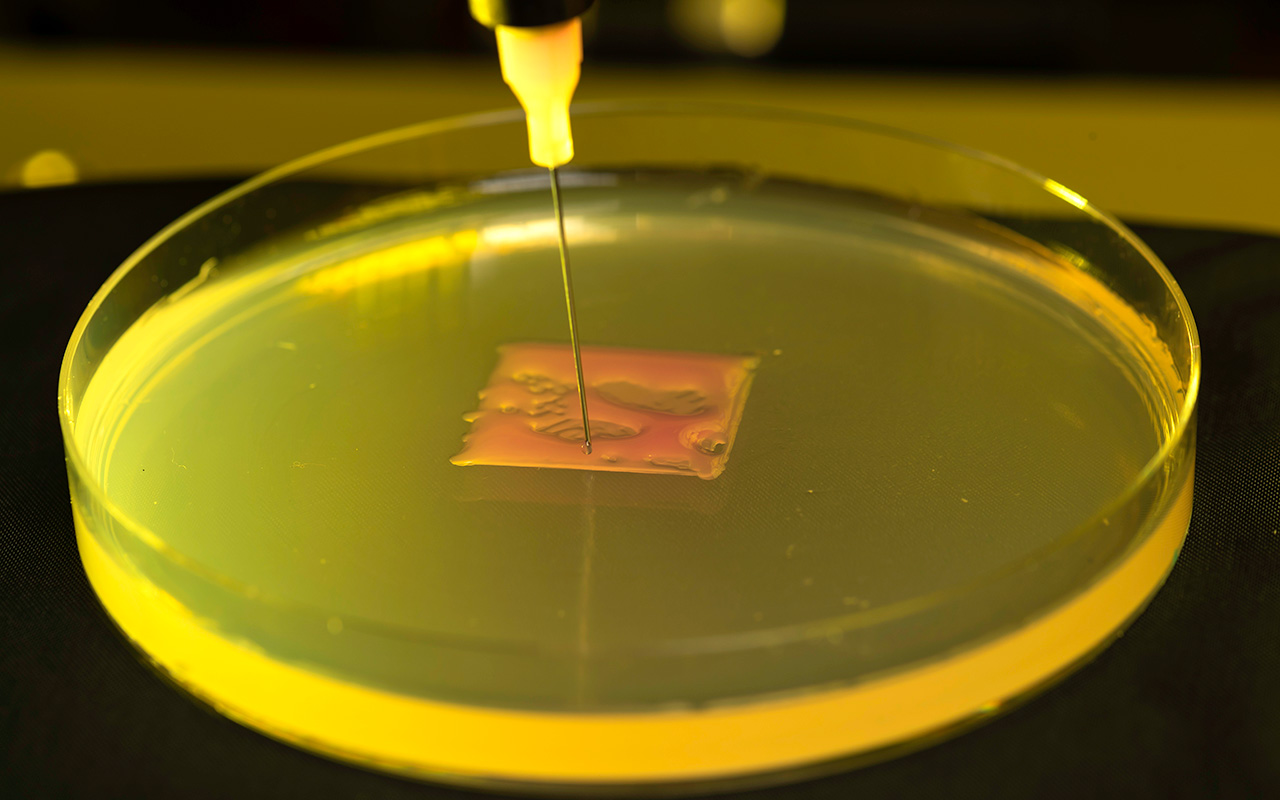

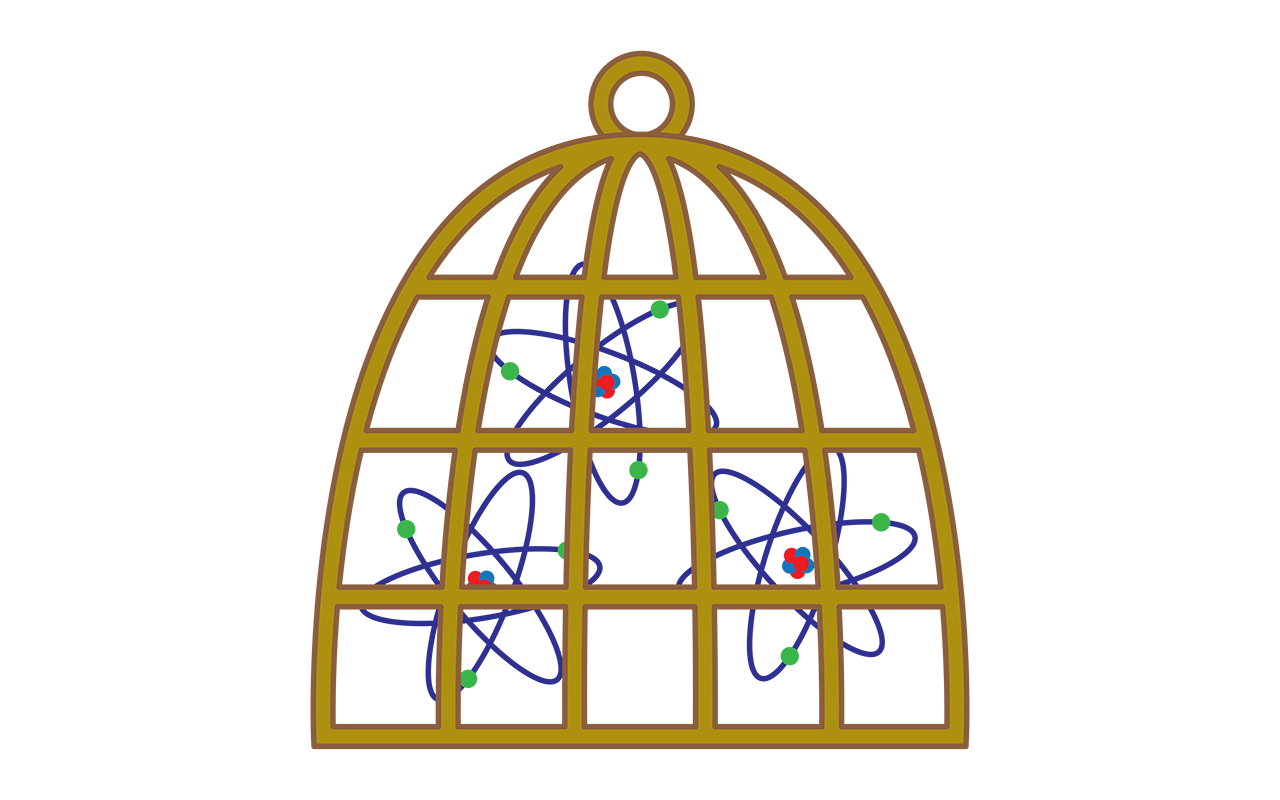

First described by her team in 2012, this previously hidden network of channels parallels blood vessels to pump cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through brain tissue, clearing toxic waste such as beta‑amyloid and tau proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Waste clearance is most active during non-REM sleep, when the glymphatic system synchronizes oscillations of norepinephrine, cerebral blood volume, and CSF flow.

Nedergaard codirects the Center for Translational Neuromedicine, which maintains research facilities at URochester and the University of Copenhagen. She has received numerous accolades, including the 2024 Nakasone Award from the International Human Frontier Science Program Organization. Her lab’s contributions offer new insights into how glymphatic function slows with age and gets impaired by disrupted sleep, high blood pressure, and traumatic brain injury. Ongoing research also includes how the glymphatic system influences the progression of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases.

The significance of this research extends to clinical concerns about sleep aids. In a study published in February in the journal Cell, her team demonstrated that the common sedative zolpidem (sold under the brand name Ambien, among others) suppresses the glymphatic system in mice. This might hinder the brain’s natural waste-clearing processes, setting the stage for neurological disorders. By establishing a mechanistic link among norepinephrine dynamics, vascular activity, and glymphatic clearance, Nedergaard’s work underscores the importance of preserving natural sleep architecture for optimal brain health.

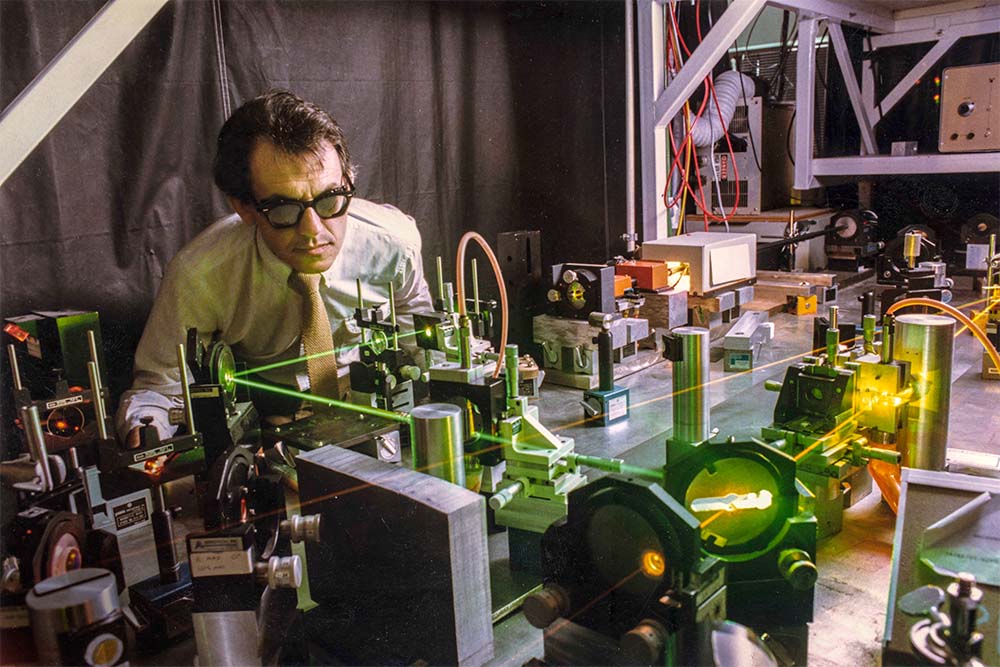

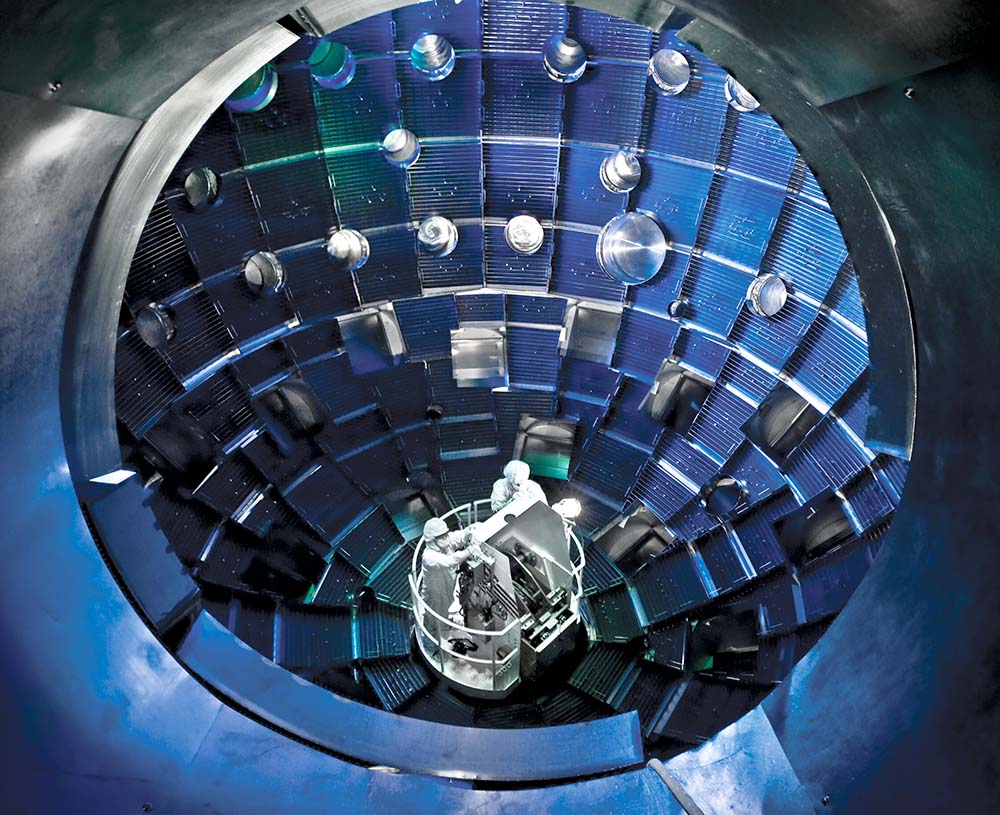

Building on these foundational insights, in 2022 Nedergaard secured a $15 million NIH grant to dissect the mechanics controlling CSF movement, involving multidisciplinary teams from URochester, Penn State, Boston University, and Copenhagen. Recent collaborations with mechanical engineers in the Hajim School demonstrated that a hormone-like compound, prostaglandin F₂α—currently used to induce labor—can revive age-related declines in cervical lymphatic vessel contractions in mice, restoring CSF clearance to youthful levels.

Globally, Nedergaard’s research has catalyzed new avenues for therapeutic development, from enhancing drug delivery to the central nervous system to designing sleep interventions that bolster brain waste removal. Her discoveries continue to influence neuroscience, biomedical engineering, and clinical practice around the world, offering hope for preventive and restorative strategies against age-related neurological disorders. MM

88. If we target cancer cells, can radiation cause less damage?

88. If we target cancer cells, can radiation cause less damage?

93. What does sleep do besides just give us rest?

93. What does sleep do besides just give us rest?